LONDON • France used to be known as the European Union's weaker link, a state not only unwilling but also increasingly unable to apply the economic reforms necessary for the 21st century, a nation buffeted by bad ethnic relations at home and the forces of globalisation overseas, a country ripe for takeover by extreme nationalist politicians.

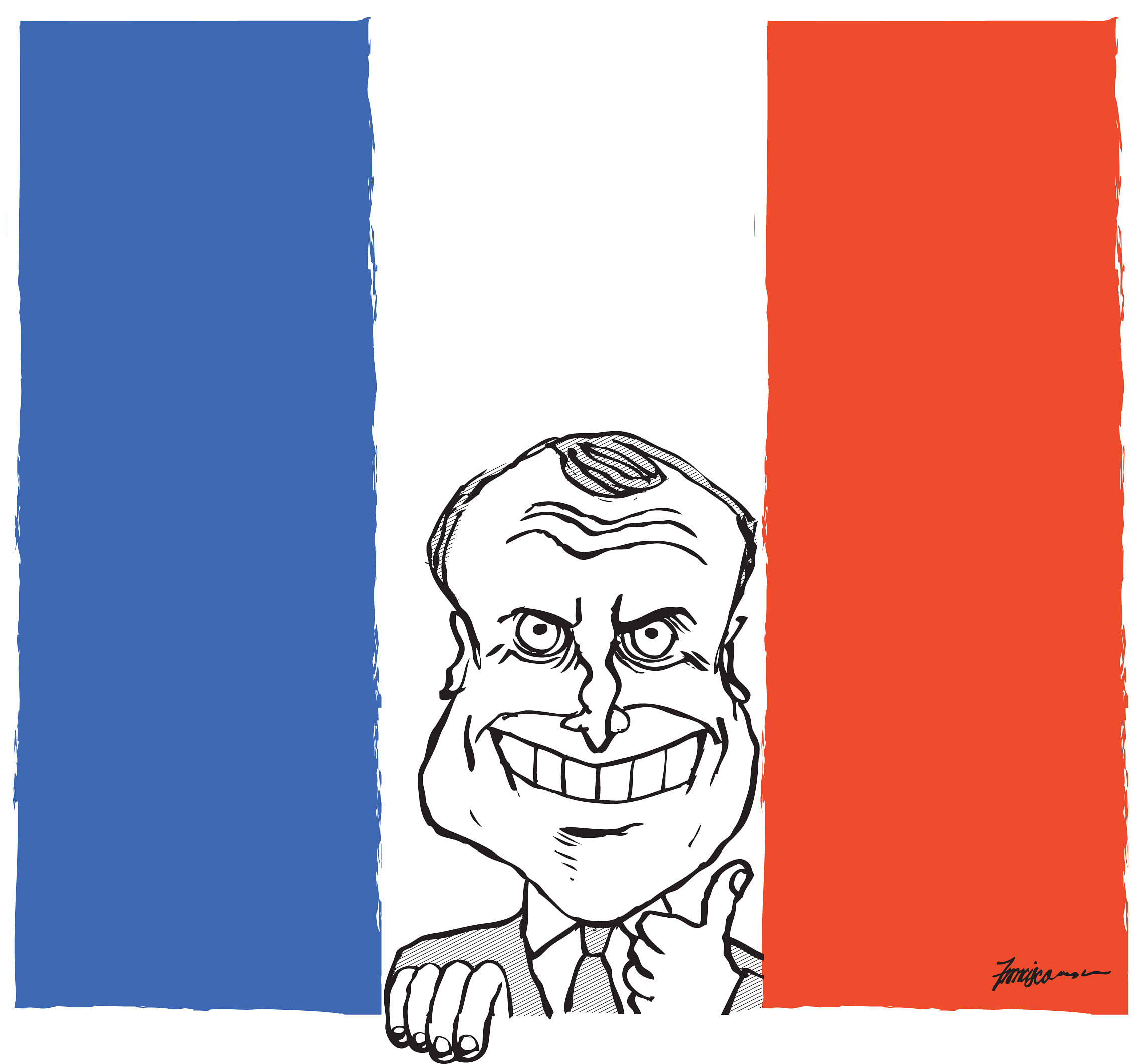

But the recent victory of Mr Emmanuel Macron, a moderate, professionally competent and highly intelligent 39-year-old independent politician in the country's first round of presidential elections - and the near certainty that he will be elected as France's youngest head of state in a week from now - has transformed the nation's image.

Politicians throughout Europe are talking excitedly about a France which will, yet again, become the motor of the continent's integration, more than compensating for the blow of Britain's departure from the European Union. French intellectuals - always a breed apart in a country which takes its thinkers seriously - are dreaming again about a French society about to be reinvented.

And even the usually restrained Financial Times, that bible of English-speaking capitalism which the French mistrust so much, is now writing with anticipation about the possibility that, under the rule of the reformist and enterprise-friendly President Macron, Paris may well end up replacing London as Europe's premier financial trading hub.

Not so fast, or not so soon. For although the impending election of Emmanuel Macron is undoubtedly a welcome development, the France which Mr Macron will inherit has seldom been as divided about its future as it is now. And, although a French head of state enjoys very considerable powers, he will enter the Elysee presidential palace with almost no political structure to sustain his rule.

It's in Europe's interest that Mr Macron succeeds. It is, however, also in Europe's interests not to exaggerate his prospects of success.

LUCK AND LE PEN

To start with, it's worth recalling that, although Mr Macron topped all other candidates in the first round of France's presidential elections, he barely got the support of one in four voters, enough to get him into the second round but hardly a decisive endorsement.

Furthermore, his rise to power is not due to his ability to galvanise and persuade the French electorate about the righteousness of his cause but, rather, to a unique set of events which even Mr Macron himself could not have predicted.

These included the fact that Mr Francois Hollande, the current president, is so unpopular that he decided not to stand for office again, as well as the ruling Socialist party's decision to put forward a presidential candidate who was basically unelectable and who scored one of the worst results for any mainstream centre-left candidate in France's history over the past century.

Add to that the surprise choice of the mainstream centre-right Republican party, which picked as its presidential contestant an aristocratic gentleman who got mired in personal financial scandals from the first day of the electoral campaign, and it becomes clear that Mr Macron triumphed not because he knocked out his opponents, but because they knocked themselves out.

All successful political careers require a large measure of luck, so nobody should begrudge Mr Macron his success. But it is important to note that this French election witnessed the spectacular rise of another politician who also came out of nowhere: Jean-Luc Melenchon, a far-left candidate who advocated pulling France out of international trade agreements and taxing the "rich" - by which he meant income above €400,000 (S$609,000) - at a rate of 100 per cent.

The fact that this sort of left-wing version of America's Donald Trump got almost 20 per cent of the vote in the first round of the French ballots, just a few percentage points behind Mr Macron, indicates that there is no consensus in France about the urgent need for market-based economic reforms. Either way, Mr Macron is not France's equivalent of Margaret Thatcher, the British leader who won power in the late 1970s on an explicit campaign of radical change and proceeded to do precisely that.

Neither can Mr Macron claim to be the slayer of France's nationalist and racist extremists. For, while he is likely to defeat Ms Marine Le Pen, the leader of the anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant National Front in the second-round ballots which will be held on Sunday, more French men and women voted for Ms Le Pen than those who voted for the mainstream left and right political parties put together, an astonishing outcome.

And, at 22 per cent of the votes in the first round, Ms Le Pen scored far better than the performance of her father, who also qualified for a second round of the presidential elections in 2002.

If Mr Macron prevails on Sunday, that will be because politicians of every stripe will back him in preference to the National Front candidate. But, since the National Front itself continues to increase its share of the vote with every ballot, all the current elections mean is that France is merely postponing its day of reckoning with a populist mass movement which rejects almost everything the French Republic stands for. That's an achievement, but a very modest one.

TOUGH REFORMS

And then, there is the critical issue of building a political consensus after the presidential elections are over. For, if Mr Macron becomes leader, he will be the first president in more than half a century since the current Constitution was put in place to start governing without a political party of his own; he has run the campaign as an independent, as a man who is both of the left and of the right, or of nowhere in particular.

As president, Mr Macron will enjoy broad powers of patronage which include that of appointing the prime minister, so he should not have too much difficulty in forging his own "presidential majority". Still, that will be a precarious affair.

As a former member of a Socialist government, Mr Macron may be tempted to rely on his old colleagues. But the Socialist party may be in terminal decline, and is most unlikely to command a majority in the parliamentary elections which will follow next month. And, although the centre-right Republicans may be amenable to helping President Macron if he offers them a "cohabitation" in power, the Republicans have no incentive in doing the bidding of a head of state who is not one of their own and who is responsible for their current electoral misfortunes.

Furthermore, it would be odd if any government which Mr Macron manages to put together will agree to shoulder the unpopularity of radical economic reforms which France needs and which must include cuts in state expenditure, a longer working week, a slimmer health service and lower pensions, while, at the same time, allowing the president to remain above the political fray. A far more likely scenario is that all reforms will be watered down, or postponed to the future, notwithstanding Mr Macron's promises.

In any case, the new president won't have much time to forge a parliamentary majority: Between the moment he enters the Elysee palace and the start of the parliamentary electoral campaign, he has precisely 10 days to cajole and promote people who may be close to him. For the moment, none of the political parties entering Parliament has a clear idea what the future president wants.

A Macron presidency will clearly boost the EU politically, largely because it will strengthen the Franco-German link. Mr Macron has already threatened that, if he comes to office, he will demand the imposition of sanctions against Poland, an EU member state whose politics he does not like; like all French leaders before him, Mr Macron's idea of Europe is that of a continent in which France and Germany say what needs to be done, while the others are told "not to miss an opportunity to shut up", as a former French president admirably put it a decade ago.

Still, when it comes to his own country's economic revival, radicalism will be replaced by caution. For, as Georges Danton, one of the key radical leaders of the French revolution more than two centuries ago, once remarked in reference to the policies of all rulers in Paris, "we destroy only what we replace".

Like his predecessors, Mr Macron is aware of what needs to be destroyed to make France great again, but he will struggle to get a consensus on what needs to replace it.