The Australian state of Victoria recently legalised assisted suicide. This law, when enacted, will enable a resident who has lived in Victoria for at least a year, and who has a terminal, incurable illness with a life expectancy of less than six months, to obtain a lethal drug to commit suicide.

Victoria has now joined the ranks of the Netherlands, Canada, Belgium, Colombia and Luxembourg which have legalised euthanasia. Several states in the United States, including California, Washington, Vermont and Oregon, have passed laws allowing assisted suicide.

In physician-assisted suicide, a physician supplies a lethal drug or suggests a means by which a patient will use it to complete the act that brings about death.

In euthanasia, the physician performs the act of directly injecting the medication to cause death. These terms do not apply to a patient's refusal of life-support measures, or to the request for these life-prolonging measures to be withdrawn.

We would think that it would be terminally ill patients with grievous and irredeemable pain who are most likely to want physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia, but the laws permitting this were mainly motivated by the concerns of the "worried-well" - by healthy people who fear the unknown future and the possibility of dying painfully, and who want that control and assurance that they can have the legalised means to end their lives if things become unbearable.

But empirical studies of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in the Netherlands and the United States indicate that pain played a relatively minor role in motivating requests for assisted suicide. These studies showed that in only 11 to 32 per cent of all cases was pain the reason for requests for euthanasia.

Depression, general psychological distress, and fear of a loss of control or dignity, of being a burden, and of being dependent on others, were the common reasons. This prompted oncologist and bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel to ask (in an article published in The Atlantic) if the wishes of these patients should then be granted. He followed with this riposte: "Our usual approach to people who try to end their lives for reasons of depression and psychological distress is psychiatric intervention - not giving them a syringe and life-ending drugs."

SLIPPERY SLOPE

One of the biggest - and perennial - concerns of legalising physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia is that it will lead to the "slippery slope".

The slippery slope argument contends that even a relatively conservative law like the Victorian model would evolve over time, becoming more permissive and with the right to receive assisted suicide extending to many others: from physician-assisted suicide for the terminally ill and fully consenting adults to euthanasia for patients who cannot give consent - the unconscious, severely disabled children, and the mentally ill.

And it seems to be happening in a couple of countries.

In the Netherlands, which was the first country to legalise euthanasia in 2001, there is the Groningen protocol. Written in 2004 at the University Hospital of Groningen, it was authorised by the Dutch Association for Paediatric Care the following year as a national guideline to help doctors decide when to actively end the life of a newborn. These include infants with severe underlying disease who will die despite optimal care; infants with severe brain abnormalities or extensive organ damage who are dependent on intensive care; and infants with a hopeless prognosis who do not need intensive care but experience what parents and medical experts deem to be unbearable suffering. An example of this last group would be a child with the most serious form of spina bifida (a congenital birth defect of the vertebrae and spinal cord) who is expected to have an extremely poor quality of life despite many operations.

Belgium, which legalised euthanasia in 2002, further amended its law in 2014 to allow for the euthanasia of terminally ill children. The law also allows euthanasia for patients suffering "unbearably" from any "untreatable" medical condition, terminal or non-terminal, including mental disorders. The law has been used for patients with autism spectrum disorder, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depression - which, as a psychiatrist, I find profoundly disturbing.

Psychic suffering is often temporary and with proper treatment, patience and time, would lessen. I would consider the labelling of even severe mental illnesses as "untreatable" truly questionable, as the course of these illnesses may fluctuate; the prognosis is uncertain; and in no way would mental illnesses be considered "terminal". Further, the presence of a mental disorder could affect the mental capacity to make an informed decision.

The slippery slope argument also raises a practical concern: If assisted suicide were legalised, there must be regulations to ensure that a patient's decision for suicide is informed, competent, and made without any external coercion. There must be a tight process of robust vetting, assessment and consultation. The doctor has to provide detailed information, including the diagnosis and prognosis, and possible treatment options, and assess the patient's mental capacity to make that fateful decision.

But the danger is that such regulations and safeguards cannot be adequately enforced in practice, and that particularly vulnerable patients - for example, the aged and those with severe disabilities - might be pressured into accepting assistance in dying when they do not really want it.

There may be that additional indirect pressure when the onus of responsibility is being shifted to these patients who may then be seen to have the power to end their suffering; and refusing would be seen as the patient's own doing - something which might even engender resentment in overwrought caregivers who are physically, emotionally, and financially exhausted.

PALLIATIVE CARE

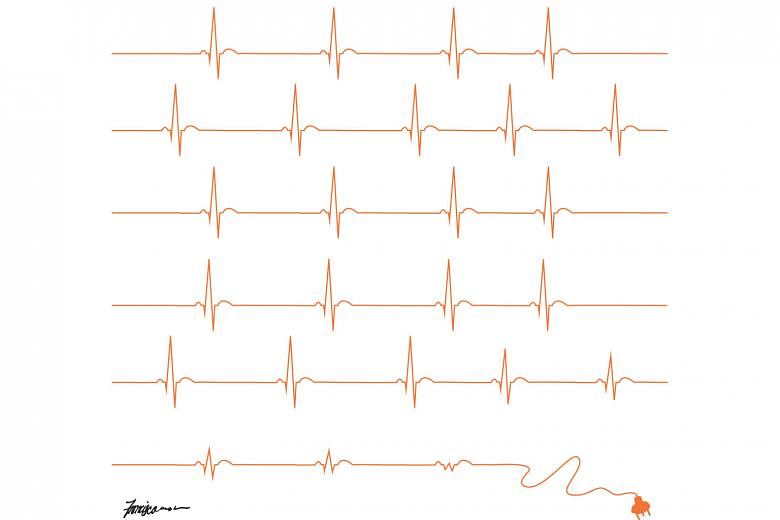

I have lived long enough and worked long enough as a doctor to witness heart-wrenching cases of individuals who suffered a slow and difficult death, and in such instances, assisted suicide and even euthanasia seemed to be the most humane option.

But I'm troubled by the potential effect that the legalisation of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia would have on doctors should such measures become routine and we become too comfortable in prescribing and giving injections to end life. It seems anathema to what doctors do, and violates a core tenet of the Hippocratic Oath that we had sworn the day we became doctors, which is "first, do no harm".

And, it could also undermine the nature and quality of the doctor-patient interaction which is a relationship that is built on trust; most dying patients, even when suffering, would also want to live as long as possible and expect their doctors to respect this and trust that they would help them and not push them to end their lives. We certainly would not want to raise the spectre of Jack Kevorkian, the Michigan pathologist who went on a zealous crusade to assist some 130 people to end their lives with his makeshift "suicide machine" that administered a lethal injection to them or allowed them to inhale carbon monoxide before he was convicted of second-degree murder and imprisoned.

Professor Ezekiel Emanuel writes: "Providing the terminally ill with compassionate care and dignity is very hard work. It frequently requires monitoring and adjusting pain medications, the onerous and thankless task of cleaning people who cannot control their bladders and bowels, and feeding and dressing people when their every movement is painful or difficult. It may require agonising talks with dying family members about their fears, their reflections on life and what comes after, their family loves and family antagonisms. Ending a patient's life by injection, with the added solace that it will be quick and painless, is much easier than this constant physical and emotional care."

And he warns that resorting to this quick way of exiting, which also obviates all this hard work, would be tempting and makes it difficult not to use it, particularly in an overburdened healthcare system.

In his book Being Mortal, surgeon and writer Atul Gawande also cautions that this "capacity" of assisted suicide could "divert us from improving the lives of the ill". He thinks that the growing number of assisted suicides in the Netherlands, where the system has existed unopposed for decades, is not a measure of success but a measure of failure.

He posits that it could be because the Dutch have been slow in developing a system of palliative care and this tardiness stems from their entrenched system of assisted suicide and euthanasia that might have "reinforced beliefs that reducing suffering and improving lives through other means is not feasible when one becomes debilitated or seriously ill".

The goal of assisted suicide/euthanasia and palliative care is purportedly to relieve suffering, but their means are different: the former does it by stopping life while the latter tries to reduce suffering by treating physical, psychosocial and spiritual distress.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010, which evaluated the potential benefits of early palliative care among a group of patients with terminal lung cancer, described the "specific attention" given to assessing "physical and psychosocial symptoms, establishing goals of care, assisting with decision-making regarding treatment, and coordinating care on the basis of the individual needs of the patient" as part of palliative care. The researchers found that those who received palliative care not only chose less aggressive therapies but also lived longer and had better quality of life compared to those who received the usual care.

The truth is that even if the most terrible pain in a terminally ill patient can be eased, there could be other distressing symptoms like nausea that is the side effect of powerful pain-relieving medication, extreme fatigue, breathlessness, the humiliating loss of bodily functions, and the terror of impending death.

But these may be indicators that not everything possible has yet been done and perhaps, we have to hunker down and do more of the sort of hard work described by Prof Emanuel.

If we could ensure that terminally ill patients have access to good palliative care and compassionate mental health attention, then we would probably think less and want less of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

The medical profession is dedicated to preserving life when there is hope of doing so, and even if there is no more hope and death is imminent, we should and could alleviate suffering. "Our ultimate goal, after all, is not a good death," Dr Gawande said, "but a good life to the very end."

- Professor Chong Siow Ann, a psychiatrist, is vice-chairman of the medical board (research) at the Institute of Mental Health.