In September 2003, I found myself in the German city of Hamburg for a significant event in Singapore's legal history - the city state's first appearance before an international court.

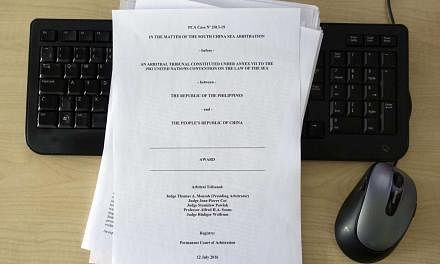

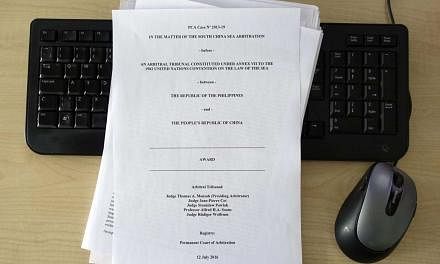

Unhappy with Singapore's reclamation works off Tuas and at Pulau Tekong, Malaysia had launched legal proceedings against its neighbour, as provided for by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, or Unclos. This action, known as compulsory dispute settlement, was similar to that taken by the Philippines against China over the South China Sea. One difference was that while China refused to participate, Singapore took part and took pains to argue its case.

A three-day hearing was scheduled at short notice because Kuala Lumpur sought a stop-work order. I was one of two journalists sent to Hamburg to report on it; the other was from Malaysia.

The court in question was the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, also known as Itlos. It has 21 judges. I noticed that when the Singapore delegation arrived at the court, several of those judges greeted Ambassador Tommy Koh, Singapore's agent for the case, with great warmth and shook hands with him as though they were old friends.

I realised later that this might have been due to the important role Ambassador Koh played in the passage of Unclos, a landmark treaty negotiated over nine years to bring law, order and peace to the world's oceans and seas. He had presided over those difficult negotiations in their last three years, from 1980 to 1982, when Unclos finally became international law and set a new record by being signed by 119 countries on the first day it was open for signatures.

Unlike Ambassador Koh, I am not trained in international law. The reclamation hearing was my introduction to it. I would receive a deeper immersion five years later, in 2008, when I would report on Singapore and Malaysia's oral arguments in their territorial dispute over Pedra Branca, which went before the International Court of Justice at The Hague. That hearing took not three days but three weeks.

I saw up close Singapore's leading minds in public international law work flat out with colleagues from various other agencies, to defend, in the first case, Singapore's right to reclaim land in its own waters, and, in the second case, to continue its exercise of sovereignty over Pedra Branca. Ambassador Koh, then Deputy Prime Minister S. Jayakumar, then Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong and Judge of Appeal Chao Hick Tin were passionate about international law, as citizens of a small state have cause to be.

As Ambassador Koh explained in a recent commentary for The Straits Times, international organisations like the United Nations and international law have helped to create a safer and better world governed by laws, rules and principles. "It is a world," he wrote, "in which states, big and small, are held accountable for their actions towards other countries as well as towards their own citizens. It is, of course, true that great powers have often resorted to the use of force to achieve their political objectives. However, even great powers do not want to live in a chaotic and lawless world. They prefer to live in an orderly world.

"At the same time, they claim to have the right to act against the law of nations when their vital interests are at stake. Life is, therefore, a constant struggle between the rule of law and the rule of might. It is the ambition of small countries to strengthen the rule of law and weaken the rule of might. It is the aspiration of small countries to curb the unilateral use of force by the great powers."

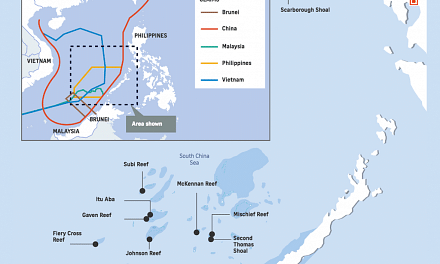

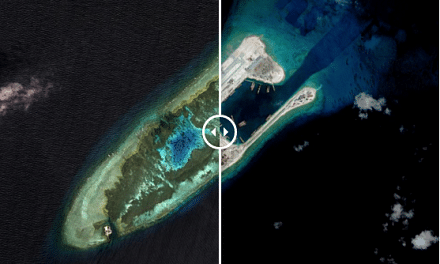

Today, the two great powers that almost all small states have to engage with are the United States and China, both of which are active in the waterways around Singapore, namely the South China Sea. The current rules-based world order is largely an American construct, and accords with American norms in areas ranging from free trade to human rights to the use of force. China is, by contrast, a regime taker.

When it opened up to the world, it found that the international community it was joining was already well regulated. It realised it had to learn the rules of the game and play by them, said Professor James Li Zhaojie, for otherwise, there was no way it could communicate, trade or conduct relations with other nations, especially "these Western law-minded countries". The professor of international law at Beijing's Tsinghua University was speaking at a 2011 panel discussion organised by the University of Pennsylvania Law School on the question: Are superpowers above the law?

Still, there is the issue of trust, Prof Li said, as international law originated in the West and was, for a long time, Eurocentric. "And China was the underdog, victimised by this Eurocentric international law for more than a 100 years, ever since the Opium War of 1842. So... should China trust Western-oriented rules of law governing relationships among nations?" he asked, before adding that, by and large, "today China does feel that it is a beneficiary of the present international legal order".

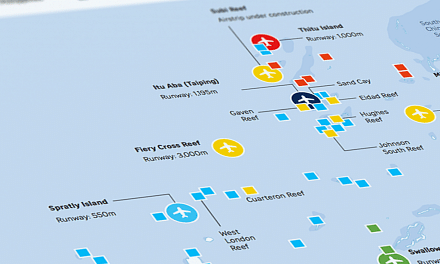

But the differences between the US and China do not end there. The gap in their approach to international law can be seen in, for example, their differing views on military activity in an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles out from a state's coast. During negotiations for Unclos, China had proposed that states should exercise some form of national security control over the waters in their EEZ, said Professor James Kraska of the US Naval War College during the panel discussion cited above. China's view was not accepted.

Now, having signed on to Unclos as a package deal, China knows that, by law, the US navy can operate in its EEZ but it nevertheless objects to such activities. Prof Kraska observed that "whereas the United States approach is very legalistic and black letter, the Chinese approach is much more of, it may be lawful but it's just not nice. It's rude and it's akin to a Peeping Tom looking in your window while walking along the sidewalk. There's nothing in the law that says you can't look in somebody's window as you're walking along the sidewalk... but it's just not nice and your neighbour doesn't like it. So I think that it gets to a difference of what global order ought to look like."

That cultural difference may also lie behind China's consistent rejection of the arbitral proceedings which the Philippines launched unilaterally, as allowed under Unclos' framework for compulsory dispute settlement.

It is significant that in the White Paper China issued the day after the arbitral award, it said on dispute settlement: "Based on an in-depth understanding of international practice and its own rich practice, China firmly believes that no matter what mechanism or means is chosen for settling disputes between any countries, the consent of the states concerned should be the basis of that choice." It also reiterated that it had held multiple rounds of consultations with the Philippines on proper management of disputes at sea and reached consensus on resolving them through negotiation and consultation. In other words, the Philippines' unilateral action, even if lawful, was not nice.

But even as China hopes for, and expects, other countries to be sensitive to its feelings, it must also appreciate that smaller states may feel they have no choice but to seek refuge in international law, which levels the playing field between them and a giant neighbour - especially one with a habit of flexing its muscles.