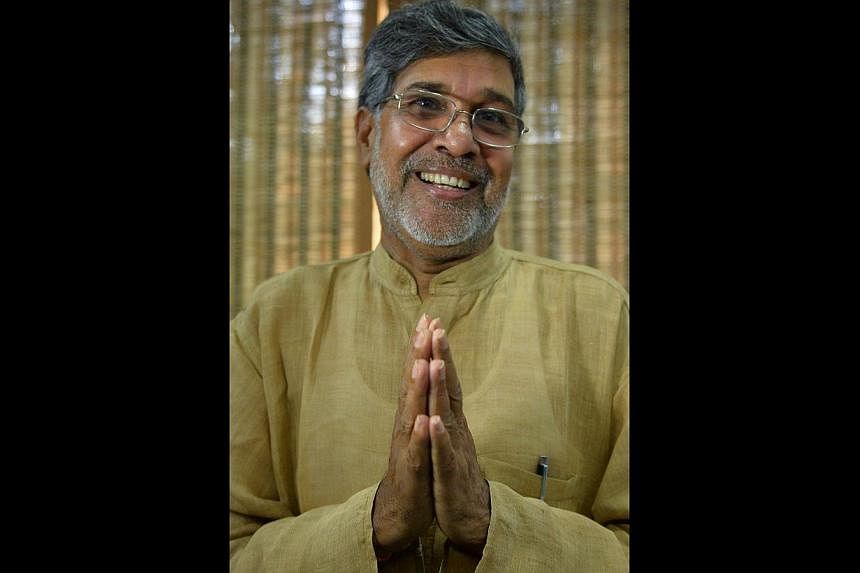

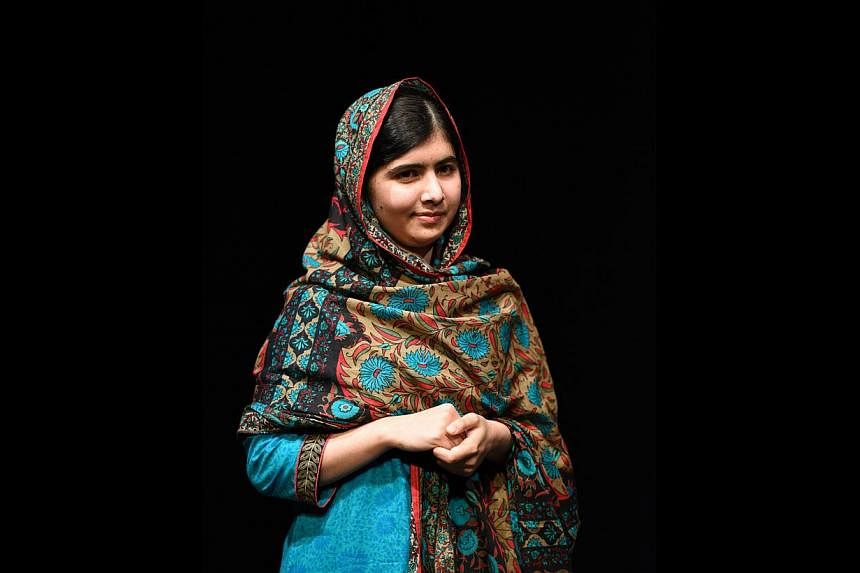

This year, the coveted Nobel Peace Prize went jointly to India's tenacious child rights activist Kailash Satyarthi and Pakistan's teenage "Braveheart" Malala Yousafzai, who has stood up for the cause of girls' education.

In announcing the decision, the Nobel Committee considered it an "important point for a Hindu and a Muslim, an Indian and a Pakistani, to join in a common struggle for education and against extremism".

The Nobel Committee has symbolically rebuked the forces of bellicosity and regression in the sub-continent.

There are many cynics who criticised the move. Yet, Mr Satyarthi - echoing the Nobel Committee and much of the civilised world after he and Malala spoke on the telephone - declared "we must also work for peace in the sub-continent. It is very important that our children are born and live in peace".

Both winners, in their efforts to eliminate child labour and provide education to deprived children, have taken up the real enemy the countries jointly confront - a jeopardised future for millions of their children.

The route to the Peace Prize for the two was totally different.

Malala, 17, the daughter of an activist school teacher, started writing her own blog for the BBC Urdu (Pakistan's national language) service at the age of 11, describing life under the Taleban who had taken over her native Swat Valley and announced a ban on girls' education.

She won instant fame when on Oct 9, 2012, a Taleban militant boarded her school bus and asked, "who is Malala?" then shot her in the head for the cause she had undertaken. Miraculously, after multiple surgeries, she survived. Her rehabilitation process continues in Birmingham in the United Kingdom, where she goes to school.

She has set up the Malala Fund and supports local advocacy groups with a focus on Pakistan and some other countries. Her bestseller autobiography is appropriately titled I Am Malala.

Speaking to reporters, she said: "I think this is really the beginning. I want to see every child going to school." The award, she says, is only an "encouragement" to do more.

Mr Satyarthi gave up a career as an electrical engineer in 1980 and has instead campaigned for 30 years against the traumatic practice of child labour in India and across the world. He founded Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Children Mission), an NGO dedicated to rescuing children from bondage and working for their rehabilitation across 140 countries. His organisation is credited with freeing nearly 80,000 children from slavery.

When others defend child labour as a social necessity for poor families, Mr Satyarthi points out that "child labour causes poverty since it leads to illiteracy".

"Without education, there can be no jobs and so people stay poor," he says. "It is a disgrace for every human being if any child is working as a child slave in any part of the world."

A Gandhi follower deeply troubled by the caste-based discrimination, Mr Satyarthi is reported to have dropped his Brahmin family name in favour of Satyarthi, which means "seeker of truth".

Child labour and child education are amongst two of the myriad social issues India and Pakistan face. For South Asia, where a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line, the absence of opportunity deprives the poor of education and a chance to climb the social ladder.

Unesco's 11th Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2014 says 94 per cent of children from poor families in India remain illiterate. Pakistan's total literacy rate is 46 per cent, but for girls, it is a much lower 26 per cent. About 28 million children, aged six to 14, are working in India, according to Unicef, the United Nations' children's agency. And in Pakistan, there are up to 10 million child workers, says Unicef child and adolescent protection specialist Mannan Rana.

According to the 2013 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Report, Pakistan ranked 146 out of 187 countries in the Human Development Index, partly due to a fall in social sector spending. India fared somewhat better at 135.

Yet, India and Pakistan have budgeted US$38.35 billion (S$48.9 billion) and US$7 billion for defence during the current financial year - 2.4 per cent of India's GDP and a wrenching 3.4 per cent of Pakistan's GDP.

By awarding the Peace Prize simultaneously to child rights activists from these two belligerent neighbours with a combined population of 1.4 billion, the Nobel Committee has thrown a challenge to the political and military leadership of both India and Pakistan. Hopefully, this awakens their conscience.

The writer is an adjunct professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He was Pakistan's High Commissioner to Singapore from 2004 to 2008.