-

GETTING THERE

-

I fly from Singapore to Amritsar in India on Scoot (www.flyscoot.com), which makes the 5 1/2-hour journey four times a week.

Vivid Amritsar

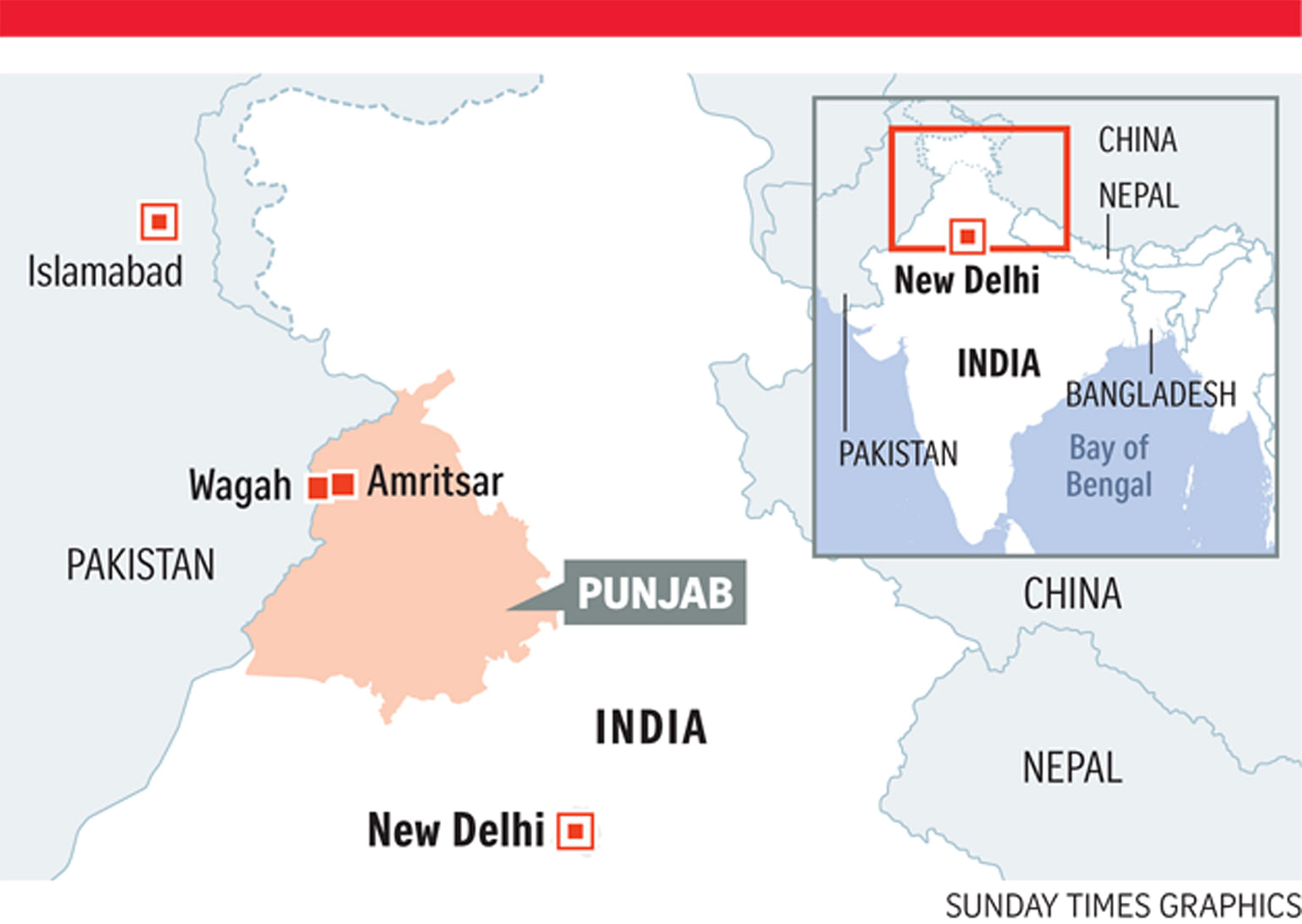

The home of the famous Golden Temple is also a base to watch the festive India-Pakistan border closing ceremony

Dust swirls, clouding the labyrinthine streets in Amritsar's Old City. It rises from the juddering wheels of an auto-rickshaw and from beneath my slippers as I walk through sandy ochre paths in this corner of Punjab in northern India.

The 10-minute walk to the Golden Temple, from Jugaadus Eco Hostel (www.jugaadus.com) where I am staying, is a colourful little journey itself.

Conversations with fellow backpackers are punctuated by frenetic honking and the ceaseless revving of sputtering vehicles laden with more passengers than they can carry.

We arrive at the temple after dusk. As I deposit my footwear, put up my hair in a requisite headscarf and wade through a cleansing foot bath at the entrance of the temple, I feel myself relax.

I have arrived in Amritsar on Scoot's inaugural flight on May 24 with four other Singaporeans and we will spend five days in this city, where the primary attraction is the Golden Temple (www.goldentempleamritsar.org).

I enter the temple courtyard (admission is free) by descending a short flight of stairs. According to our guide Gourav Sharma, this symbolises man denouncing his ego and Sikhism's denial of the caste system.

Anyone can visit the temple, which is also known as Sri Harmandir Sahib, or the Temple of God. Most Sikhs try to visit at least once in their lives.

The temple is a mass of shimmering gold rising dramatically from the pool of water it seems to float on.

Mr Sharma calls it nectar and, indeed, the city derives its name from this - Amrit means nectar and Sar means pool - a divine lake where Sikhs believe all afflictions can be cured.

"If you have faith, it is nectar," says Mr Sharma, who says he has seen a deaf and mute man speak again after praying at the Golden Temple, which was completed in 1604 and filled with rare art. "If not, it is just dirty water."

While the courtyard throngs with devotees - about 80,000 people visit the Golden Temple every day, and up to 150,000 on weekends and festive occasions - many find their own contemplative space.

A young woman sits in a corner with her eyes shut, crossed-legged, meditative. Two men, middle-aged and barrel-chested, bathe in the pool of water, seeking its therapeutic properties.

DINING WITH DEVOTEES

Besides opening its doors to visitors of all faiths, the temple also serves free vegetarian meals every day. I move along with the crowd, a river of barefoot devotees and visitors streaming from the main temple grounds into a two-storey dining hall.

We sit in rows, strangers facing one another, cross-legged on the cool marble floor. A rotund, turbaned man, carrying warm chapati in a rattan basket, drops one onto my metal plate, compartmentalised for the dhal and curry that will come later. Across me, devotees receive their bread in cupped, outstretched palms.

There is no ceremony - devotees start eating once the food lands on their plate. I follow suit, tearing the chapati into shards to mop up the fresh, spicy dhal. Dessert is a sweet, watery rice broth that would not be out of place at a Chinese dessert stall.

We eat quickly and speak little. Only our spoons clink on plates, a metallic hum that fills the cavernous hall. I finish my meal in fifteen minutes and as I rise to leave with my row, there is another line of diners already filing in to take our place. More than 50,000 people will eat tonight.

It is a system powered by thousands to feed the city's thousands.

ESCAPE FROM THE CROWDS

To escape the heat and crowds, I wake up early for a farm visit, setting out at 6am.

The farm is a half-hour journey by auto-rickshaw. Jugaadus bills it as a village tour (400 rupees or S$8 a person), but there is nothing touristy about this laid-back visit to the family home of hostel staff Jagroop Maan. Instead, entering his newly built home is like visiting an old friend.

His mother speaks no English, but welcomes us with freshly fried vegetable pakoda and masala tea. The pakoda fritters taste like spiced thick-cut French fries.

Masala tea, full-bodied and mildly sweet, is ubiquitous in Amritsar, with every restaurant serving a slightly different rendition. Fresh milk is essential in making good masala tea, and it does not get any fresher than straight from the cow.

The family owns five of them, tethered to posts in their backyard, and we try our hand at milking one. It is hefty but placid as Mr Maan shows us how to grip its teat and where to apply pressure.

It is harder than it looks. I squeeze with all my might, but manage to elicit only a thin stream. Mr Maan offers me a taste of the milk, aimed straight from the udder into my mouth. It tastes surprisingly mild, lighter than the supermarket variety I am used to.

Later, we pile onto a bullock cart and head to a freshly ploughed field, where Mr Maan and his cousins introduce us to the Indian contact sport of kabaddi. It is a mix of catching and wrestling, where the aim is to tag a member of the opposing side without being tackled to the ground.

We shed our footwear, sunglasses, cameras, mobile phones and square off. The dirt is soft under my feet as I run. A member of my team grabs his opponent by the legs and they go down writhing, grappling for the upper hand. On both sides, we whoop and cheer.

Behind me, the sun is climbing to its peak, warming the expansive fields in a part of Amritsar where there is no pulsing throng, no frenetic buzz - just us and our laughter.

DANCING AT THE BORDER

When I next encounter the crowds, it is at the India-Pakistan border crossing that lies along the village of Wagah. It costs 700 rupees to hire an auto-rickshaw that seats five to eight passengers, and we set off from Amritsar at 3pm.

I am here for the border closing ceremony that takes place every evening, along with a patriotic crowd of thousands.

Although the ceremony is characterised by dramatic military posturing from both sides, there is a festive atmosphere when I alight from my auto-rickshaw after an hour-long journey from central Amritsar.

Vendors sell ice cream and cold bottles of water, refreshing in the late afternoon heat. A young boy runs up to me, paint and brush in hand, offering to paint the Indian flag on my face. I decline, but later spot the orange, white and green stripes adorning the cheeks of many locals.

The queue for locals seems endless, but I am ushered through a separate entry for foreigners, where my passport is checked and I am patted down by a female guard, security measures that have been heightened since the 2014 suicide bombing that killed at least 55 people.

By 4pm, I am seated in the rapidly filling bleachers, even though the ceremony will not start for another two hours. Two rows of bleachers flank a strip of tarmac where the marching will later take place. Statuesque female guards patrol its length.

Bhangra music kicks in after an hour, thumping out of large speakers. Women and children holding Indian flags aloft run down the length of the bleachers, and when they pass our section of the crowd, we cheer.

This is all part of pre-ceremony festivities, complete with an emcee who rouses the crowd.

"Hindustan!" they thunder in unison, responding with fists pumped high. Seated on a concrete step, I shimmy my shoulders to the rhythmic bhangra beat, nodding in time to lyrics I do not need to understand.

The music is infectious and women spill from the stands, dancing in the street. Later, I learn from the hostel guides that this takes place every day and that only women are allowed to join the party.

The crowd grows swiftly, fuelled by young and old alike, while men watch from the stands with cameras and smartphones in the air. I join in too, though I never quite keep up with the footwork of the locals.

One teenage girl stops dancing long enough to ask where I am from, and she tells me: "We don't dance with the body, we dance from the heart."

Then she disappears back into the crowd, arms aloft, hips shaking.

The fading of the music signals the start of the ceremony. On the Indian side, about eight guards march out, wearing khaki uniforms and fan-shaped red headgear resembling a rooster's comb.

They goose-step towards the high metal gate that separates both countries, executing a dramatic, almost acrobatic series of high kicks and turns along the way.

I peer across the high metal gate that separates the countries, but can catch only a glimpse of the guards on the Pakistani side. I imagine they are performing a similar routine, each side striving to outdo the other in pomp and pageantry.

The lowering of both flags and the final clang of the metal gate slamming shut signal the end of the ceremony.

When our auto-rickshaw shudders away from Wagah at 8pm, the dust is rising again, the sky rapidly darkening.

Then our driver turns on the bhangra and I shut my eyes, finding the beat again as we dance our way back to the city, back into Amritsar's nightfall.

• Clara Lock is a freelance writer.

Where to eat

I am wary of the dreaded "Delhi belly" whenever I am in India, but these places come recommended by a hostel staff member, Mr Gurnoop Singh, and my stomach and palate agree. They are within walking distance of the Golden Temple in Amritsar and although the addresses do not contain shop numbers, locals will be able to point you in the right direction. I visited all the establishments in a morning.

BHAI KULWANT SINGH

Where: Bazar Bikanerian, near the Golden Temple

This 35-year-old stalwart is a local favourite for kulcha, a stuffed Indian bread traditionally eaten for breakfast or lunch. I try the four-mix kulcha (60 rupees or S$1.20), which is filled with potato, onion, cauliflower and cheese. It arrives crispy and flaky, gently blackened, topped with butter and served with chickpea curry.

GURDAS RAM

Where: Near the Golden Temple

Round the corner from Bhai Kulwant Singh is 65-year-old family business Gurdas Ram, which sells Indian sweets jalebi chowk and gelab jamun. These are made from wheat flour, deep-fried and served in syrup. A serving costs 50 rupees and can be shared as it is too cloying for one.

TELEPHONE EXCHANGE PANEER BHURJI

Where: Pyara Lal (telephone exchange), near the Golden Temple

This hole-in-the-wall shop serves an aromatic stir-fry of tomatoes, onions and paneer (cheese), which I spoon onto slices of white bread that accompany the dish. One portion, which goes for 120 rupees, comes with four slices of bread and can be shared by two.

KESAR DA DHABA

Where: Chowk Passian, near the telephone exchange

Palak paneer, or spinach with cheese, is a common dish that this hundred-year-old restaurant does well. I order it with paratha, crispy flatbread that I dip into the spinach puree (150 rupees).

GIAN DI LASSI

Where: Opposite Regent Cinema, Katra Ahluwalia

I round off my food trail with a tall steel glass of lassi. The yogurt drink (35 rupees for a full portion, 20 rupees for half) is available in sweet or savoury, topped with a dollop of cold butter. I pick the sweet option, passing on the butter, and it is rich and creamy - a refreshing end to the morning's indulgence.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on August 14, 2016, with the headline Vivid Amritsar. Subscribe