While Pompeii eerily conveys the brevity of life, Rome seems to glorify Man's ingenuity in grasping eternity through art, engineering marvels or faith.

Walking through Pompeii (www.pompeiturismo.it; admission starts at €11 or S$19), I try to conjure up a sophisticated city of 13,000 souls who walked on streets embedded with white-pebble reflectors.

They snacked on "fast food" from storefronts, where petrified food remains in terracotta pots. Like us, they relaxed in spas and saunas. On the women's side of the spas are little pots of make-up.

The rich lived in fancy villas, remarkably preserved under 6m of ash. Pompeii had legal and political systems, evident in its courthouse and Roman forum.

An intricate drainage system was woven into the city. There were brothels with little drawings that advertised the erotic specialities of the women.

Founded in the seventh century BC, the prosperous merchant city is an unparalleled picture of old Rome for two million visitors annually. For nearly 1,700 years, the city in the Naples region lay buried, before excavation by the French and British began in the 1700s. The 66ha site is still being dug out.

Most poignantly, there are hundreds of plaster casts of inhabitants, both humans and animals, captured in their dying moments, that symbolise the tragedy of Pompeii.

In recent years, Pompeii has endured fresh tumult, with walls and columns in the Unesco-listed site suffering damage or collapsing. Just this month, the wall of a tomb fell. Blame it on heavy rains and mismanagement.

I do not discern egregious neglect when I visit, possibly because a massive €105-million restoration, funded by the European Union, had began last year.

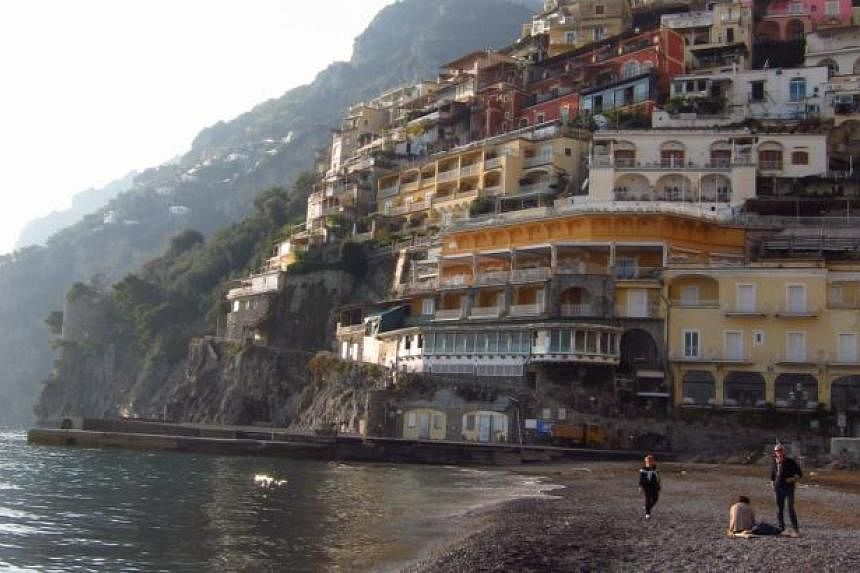

Vesuvius, 8km away, last erupted in 1944 and looms over the ruins. Fatalistic Neapolitans have returned to live and farm on its fertile slopes.

Both Pompeii and Rome illuminate the past. The Roman past is very present in the imposing Coliseum with its gladiatorial brutality, Michelangelo's Renaissance art on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and even a small, spiral staircase in the Vatican.

The Bramante Staircase, generally closed to the public but open to Trafalgar guests, was built as a secondary entrance for Pope Julius II in 1505. The step-less staircase was also a ramp for mules and horses.

The double-helix staircase is an optical illusion - I look up and down and it seems very high, though it is set inside a 19m tower. Clever Romans. The concept has been copied across Europe.

In Rome, a new friend and I explore the city soon after we get off the plane, so immediate is the city's allure. Rome is really an immense archaeological site, very walkable, and awaiting discovery with a map.

We walk along the banks of the Tiber, which divides the city, and pop into the Villa Medici with its Borghese gardens.

We get a little lost looking for a gelato shop - but will return to it a couple more times for my icy rum-andchocolate treat - and find the Trevi Fountain and Spanish Steps meanwhile.

Everywhere, there are echoes, of geniuses, of gladiators, and of life fully embraced in eras past.

Rome makes me reflect again on Pompeii, which has fascinated me since I learnt about it as a young traveller.

Now that I have stepped through its door to the past, I see a beautiful fallen city that epitomises for me what is curious and transforming when we wander.