Far off the tourist trail, the dilapidated port-city Kawthaung has a secret.

This greying town at the southeastern tip of Myanmar is an unlikely gateway to paradise, and it is here that I begin my unforgettable voyage.

The Mergui Archipelago, 800 islands of pristine tropical paradise, begins west of Kawthaung in the Andaman Sea and extends some 300km up the coast.

It is what Phi Phi Island and Phuket, down the coast in Thailand, were 100 years ago - crystal clear water, spectacular snorkelling and fiery sunsets in places still undiscovered and unspoilt by mass tourism and resorts.

Its beaches rival the best of those in the Maldives and Boracay, with one supremely satisfying difference: the splendid solitude.

Only a couple of small resorts have been built on the islands - though there are reportedly plans to develop more in the future - so the only way to explore this semiremote paradise at the moment is by boat. With so few people venturing to the Mergui, and so many islands to choose from, it is easy to feel like you have discovered your own private paradise.

Burma Boating is one of four companies - including Intrepid, Mergui Princess and Island Mergui Safari tours - which are authorised to charter cruises in the archipelago, a national park.

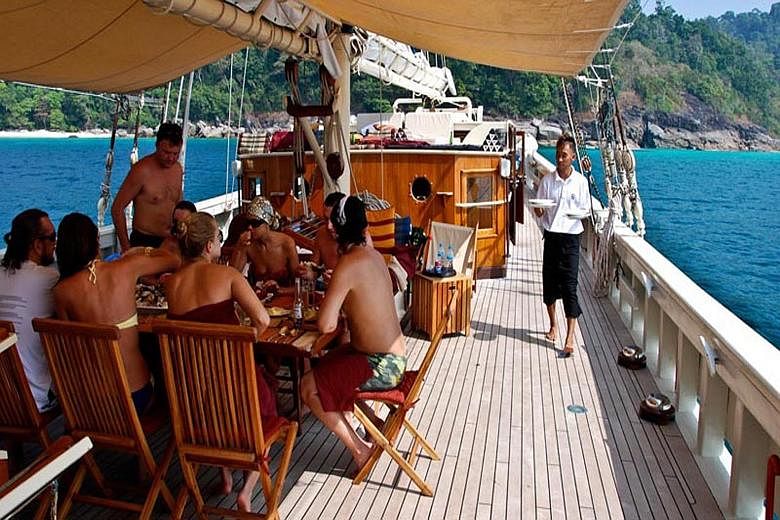

In the four days I spend touring the islands aboard the SY Raja Laut, a 30m gaff-topsail schooner run by Burma Boating (www.burmaboating.com), which organises sailing holidays in South-east Asia, we see only one other small group of tourists, who are also on a Burma Boating cruise, as we anchor off a fishing village.

Most of the time, when we enter a bay to snorkel or drop anchor, our beautiful 19th-century-styled boat, with four cloud-coloured sails and an ironwood hull, is the only vessel there.

When we are ferried by a small speedboat to an unpopulated beach, ours are the only toes which touch the crystalline waters and walk its crescents of powdered sand.

Here, there are no umbrellas, beach chairs or beachside table service. There are just eight of us - a Bangkok-based French couple, four Germans, one Spaniard and me - on board the five-night charter, enjoying a vast stretch of virgin beach, sitting in the shade of a low hanging branch and floating on waters which are the essence of aquamarine.

-

GETTING THERE

Kawthaung, a port city on the southern tip of Myanmar, is the gateway to the Mergui Archipelago.

How you get there depends on your overall itinerary.

If the Mergui is part of a greater tour of Myanmar, you can fly into Kawthaung's regional airport on Myanmar National Airlines (www.flymna.com). The flight from Yangon to Kawthaung takes two to three hours, with a stop in Dawei or Mawlamyaing. Tickets cost about US$200 (S$270) for a round trip.

Air Mandalay and Yangon Airways also have flights from Yangon to Kawthaung, though their flights are less frequent and take a longer time.

Most of the airlines operating in Kawthaung have a tendency to be unreliable, and delays, cancellations and earlier departure times are common. Burma Boating is aware of these difficulties and is typically able to accommodate last-minute changes in travel plans.

The more reliable entry point is through Thailand. Kawthaung sits across the Kraburi estuary from the Thai town of Ranong.

Visitors from Singapore can fly into Bangkok, then take a Nok Air flight (www.nokair.com) into Ranong, followed by a 30-minute, 500 baht (S$20) taxi ride to the longtail pier. Alternatively, fly into Phuket and take a four-hour drive north through forested mountainside and rubber plantations to Ranong.

I chose this option and found the drive in an air-conditioned taxi pleasant. It costs €140 (S$210) and can be organised through Burma Boating.

Once at the longtail pier, travellers must go through immigration before taking a longtail boat - which can also be arranged through Burma Boating - for the 40-minute ride across the border and directly to the boat.

Burma Boating's embarkation at 3pm and disembarkation at noon are based on the morning and early afternoon arrivals of flights into Kawthaung and Ranong.

The Raja Laut sleeps 12 in six comfortable rooms below deck - three double and three twin bunks, each with air-conditioning and small ensuite bathrooms with hot showers and electric toilets.

Eight seems to be the ideal number of passengers, however. We fit perfectly around the dining table at meals and, when lounging on deck, each of us has enough space to find solitude, where we read, write or take a nap as the boat moves between islands. There is rarely the feeling of being in one another's way, as is common on smaller boats.

Sometimes there is a flurry of activity as the wind picks up and the deckhands race around to tug ropes and unfurl the sails, but this does not happen often. We are sailing in April, when the winds are low, so there is rarely more than a cooling breeze whispering across the bow. The sun is strong and the deck is calm and quiet.

Occasionally, we pass a fishing boat or see the lights of a fishing village in the distance, but rarely do we see any signs of civilisation.

The Mergui Archipelago is so remote, in fact, that there is no Wi-Fi and phone service on board. For me, this is one of the most magical aspects of the voyage. No e-mail or text messages and no alerts or phone calls. No one to check in with, no social media to scroll. We are completely disconnected from the rest of the world and the freedom of it is indescribably peaceful. It is as though, beyond our boat and our beach, no other world exists.

I spend four tranquil, carefree days reconnecting with the simple life.

All our essential needs, from the day's itinerary to snorkelling equipment and magnificent meals, are taken care of by the incredibly friendly staff on board.

Food is expertly prepared by Malaysian chef Ben Amirul in the boat's small galley kitchen. He bakes bread for breakfast, served with eggs, bacon, yogurt and fresh fruit.

Lunch is fresh and flavourful. A lightly breaded chicken cordon bleu atop a very garlicky aglio olio spaghetti and Caesar salad, and an expertly grilled fish, its moist and flaky flesh topped with a bell pepper, onion and tamarind sauce, are highlights.

Dinner is a hearty affair and another opportunity for chef Amirul to show his breadth with dishes such as a delicious beef rendang, which is served wetter than I am used to, but still full of flavour.

On one memorable night, we are served tapas and a wonderful, homemade chicken liver pate, followed by roasted lamb - served well done - with peas and roasted carrots, but my favourite that night is a giant grilled lobster, its sweet, tender meat topped with a mango, avocado and bell pepper salsa.

The meals are more than enough to fuel our lazy days on board. After breakfast, we are dropped by the tender - the boat's speedboat - to spend a couple of hours snorkelling or at our next beach or village.

Sailing in April, unfortunately, means we have hit spring tides, which have brought up silt and sand, somewhat clouding visibility in the water. The best diving conditions are from December to March, when the water is clearest and there is the least chance of rain, with whale sharks and manta rays visiting from February to May.

Still, each beach and snorkelling destination seems better than the ones before. On the last full day, we visit Say Tan Island, which has sand so fine it rises in a milky cloud as I walk through the water, turning the clear blue sea into iridescent opal.

Later, we visit Cock's Comb Island (also known as Kyet Mauk Island), where low tide reveals a 1.5m-tall, 10m-long passageway worn into a sheer cliff. We take the tender through the passage and into a turquoise lagoon.

All around the edge of the lagoon is a reef blooming with hard and soft coral. Rainbows of parrot fish, clown fish and blue-green chromis dart around sea anemones and boulders coated in the palest orange and pink pulp. The rocks and sea bed are polka-dotted with sea urchins, and feathers of cobalt blue, magenta and burgundy sway in the current.

Ours is a snorkelling trip, but the area also has a host of top diving spots for those who prefer going deeper. Outside the lagoon is a 40m drop, a highlight for divers.

Each charter's itinerary varies slightly according to the group's diving preference and the weather, as captains do their best to capitalise on available winds.

Burma Boating has six sailboats which charter three-night, fivenight and six-night cruises, which cost between €1,700 (S$2,545) and €3,400 a person.

The cost includes accommodation, snorkelling and scuba gear as well as food and drinks, though alcohol costs extra - beer is US$2 (S$2.70), wine starts at US$20 and spirits start from US$50 a bottle.

The boats are also available for private charter, at a cost of €1,500 to €6,900 a day, depending on the size and quality of the boat. A private charter on the Raja Laut, for example, costs €4,500 a day, and itineraries and menus are fully customisable to the needs and desires of those on board.

I cannot imagine anything better than spending a week or more snorkelling and island-hopping around the archipelago.

Every evening, we sip cocktails and watch a fiery sun set into the waves, painting the sky shades of amber, crimson and pink.

Every night, I fall asleep to the sound of waves lapping against the hull, lulled by the gentle rocking of the boat.

For every stress, every anxiety and every problem you never knew you had, Mergui is the antidote. Here, I do not have a care in the world and there is no where else I would rather be.

•The writer's trip was sponsored by Burma Boating.

Water babies

Moken children are said to swim before they walk. From an early age, they learn to fish and dive to great depths without any equipment, their eyes adapted to see twice as well as ours underwater.

Our first glimpse of the Moken, one of South-east Asia's last huntergatherer populations, is off Jar Lamm Kyunn, where a small flotilla of boats races to us on the Raja Laut; half a dozen dugout canoes are nimbly rowed by Moken children standing at the oars.

Many Moken do not have a nationality or identity card, so their citizenship is unclear. They have sailed the Mergui Archipelago for centuries aboard kabangs, family-sized boats hollowed from the trunk of a single tree.

But for the past decade, the Myanmar government has limited the Moken's access to their traditional fishing grounds and tried to place them in permanent settlements in the Mergui, detaching them from their unique, nomadic way of life.

About 400 Moken now live in stilt houses on the island, and the children greet us with smiling faces painted in swirls of Thanaka, a natural sun protectant made of ground tree bark. They have come to collect gifts of potato chips and cans of soda from the crew. When we venture ashore to their village, the children eagerly hold our hands to show us their homes.

Scattered around the cove are dozens of buildings on stilts, connected by plywood walkways. Some are homes, while others are small stores holding essentials such as dried fish, toiletries and beer.

The children assume control as our guides and lead us on a cement path up a steep hillside to their school and a new temple; a singleroom structure painted white with fluorescent coral motifs on the ceiling, walls and central pillars.

It is a vibrant, kitschy contrast to another temple, simple, cosy and dark and made of wood planks 15m down the slope, where a monk offers us cups of water and leads us in prayer, the children bowing reverently at our sides.

But as soon as the prayer is over, it is clear that the children are more excited about the new temple, and eagerly point out the burlesque statues of hearts and goddesses and fresh flower beds being installed along the pathway.

It seems the village is hoping to become a tourist stop like the Moken village on Surin Island in Thailand, which makes most of its money as a popular daytrip for tourists from Phuket.

The Moken used to be fishermen, but because their fishing grounds have been turned into national parks, they are often arrested or fined for not having the right fishing permits. Tourism has become an attractive source of income.

Seeing the construction, it is conflicting to realise that while our visit is doing its part to educate us on the plight of the Moken, it might be contributing to their downfall.

Government and anthropological estimates say there are fewer than 3,000 Moken living in the waters off Myanmar and Thailand, many of whom have little knowledge or memory of their nomadic life.

As we head back to our boat, I look around the village and realise the most troubling aspect about the community is that it exists here at all. It is a joy to share smiles with the Moken, so clearly at home in the water and not yet jaded by a tourists' flash, but it is also hard not to feel like an interloper.

The corruption of the Moken culture has already begun and the kabang - once an essential aspect of Moken life - is nowhere in sight.