-

GETTING THERE

The Luoyang area is served by Luoyang Beijiao Airport, 20km from downtown Luoyang.

More than 20 international airlines connect Luoyang with Chinese metropolises, as well as Hong Kong and a smattering of overseas destinations, such as Nagoya and Okayama in Japan.

Meanwhile, Luoyang has five train stations. High-speed rail services all arrive at Luoyang Longmen Station, a short taxi ride from the grottoes, and about 20 minutes from downtown.

High-speed rail is for many tourists an excellent way to arrive in Luoyang: from Xian, home of the terracotta warriors, there are 25 daily services between about 7.30am and 8pm, with a journey time of about 11/2 hours.

WHERE TO STAY

Luoyang has many low-end to mid-range hostels, with a sprinkling of top-deck accommodation, although international chains are, for the moment, thin on the ground.

Prices are generally about half what you might expect in a more fashionable city.

Christian's Hotel (56 Jiefang Road, Xinduhui, Xigong District, tel: 0379-6326-6666) deserves its status as Luoyang's classiest high-end hostelry due to its central location within easy reach of Luoyang shops, malls, restaurants and public transport, comfortable, well-appointed rooms and friendly and professional staff who are always ready to help arrange taxis, tours and airport pickups.

WHAT TO DO

The Peony festival is held from early April to early May each year. Tickets are priced higher during the middle of the month, when the greatest variety of peonies is in bloom.

City of a ruthless empress

In Luoyang, travellers can retrace the footsteps of Empress Wu Zetian, the only female monarch in Chinese history

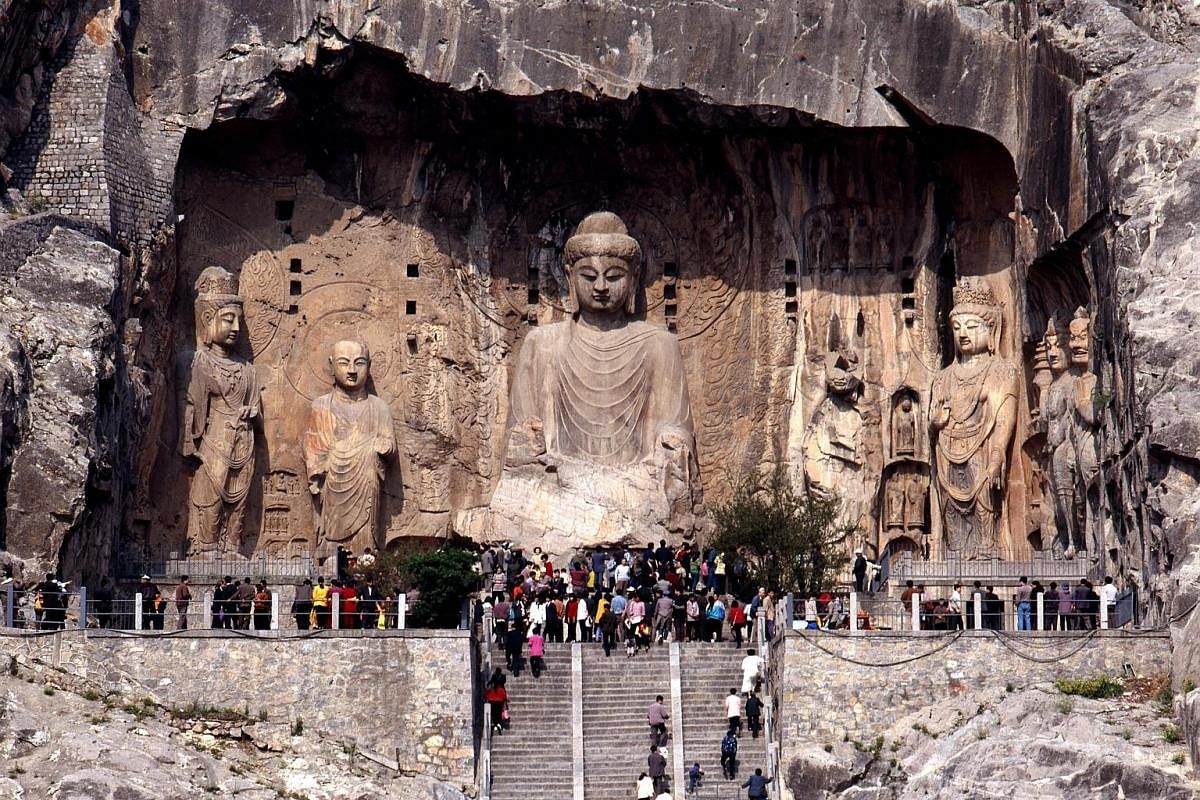

Our steep ascent to Fengxian Temple at the heart of the Longmen Buddhist grottoes in central China is observed by an impassively smiling 17.14m-tall statue of Vairocana Buddha.

The stone deity's plump face, flanked by 2m-long elongated ears, is supposed to mirror ruthless Empress Wu Zetian (624-705), the only female monarch in Chinese history.

The spectacular Buddhist carvings of the Longmen Grottoes line the cliffs of a 1km stretch of the Yi River, 25km from the city of Luoyang, where Wu was among 97 emperors to rule.

For more than 2,500 years, Luoyang was centre stage in China's history as legends walked its streets - from philosophers Confucius and Laozi to generals like Cao Cao from the Three Kingdoms era to Tang bards Du Fu and Bai Juyi.

Now, more of the city's ancient heritage, long buried underfoot, is gradually being opened to visitors and I am lucky enough to receive an invitation from one local history enthusiast to look around.

Many of Luoyang's heritage sites are associated with Wu, a former royal concubine who rose to power after apparently smothering her own infant and framing the then Empress Wang.

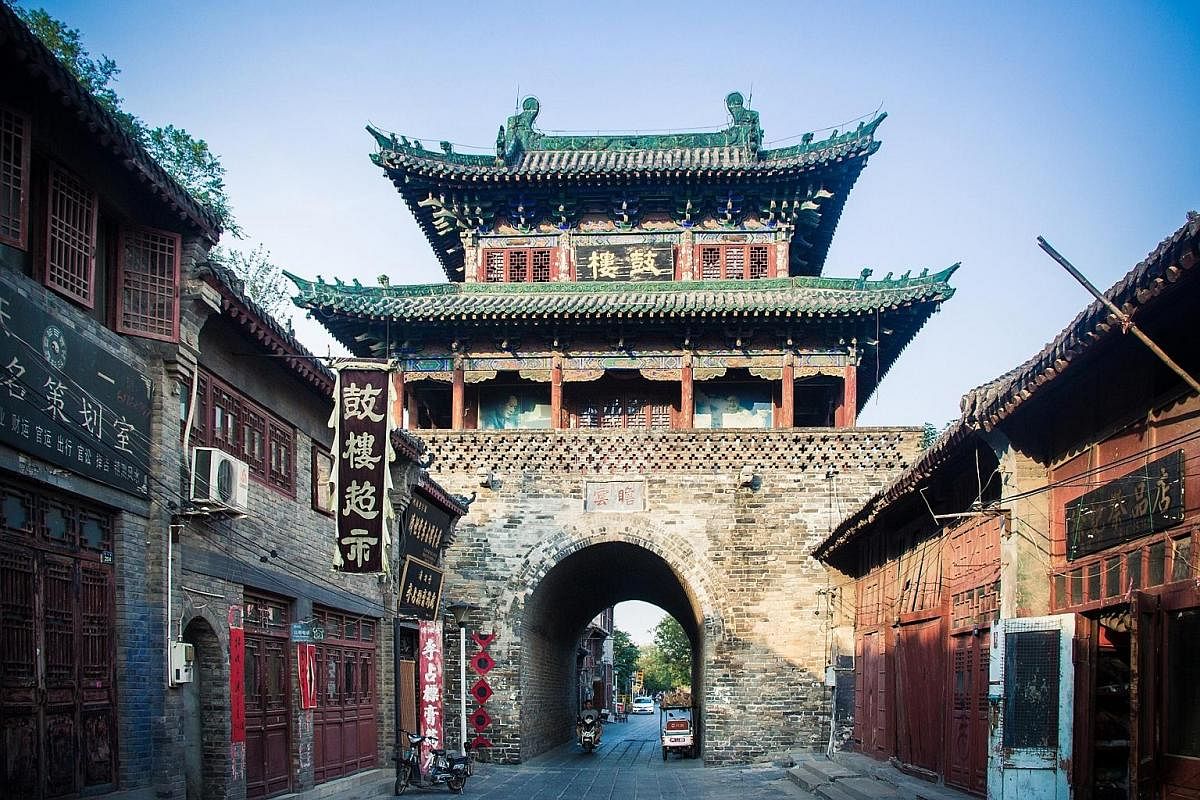

Luoyang had many incarnations during dynastic times, but our exploration begins with an ascent of the Lijing Gate - a brand-new refurbishment of a famous older Sui-dynasty (518-618) edifice.

During Wu's time, the Lijing Gate was known as the East Gate and it marked the divide between the residential city and the palace quarters.

The gate is open from 8am to 9pm (admission: 30 yuan or S$6) and, climbing the steps just before sunset, we are rewarded with a sweeping view of the modern town on one side and an eerily beautiful vista of the alleyways of the old town stretching out into yellow-tinted darkness along the river.

The lane pattern of the historic old quarter has persisted over the millennia, but in Tang times, the central axis West Street was 110m wide and paved with flagstones that carriages could roll along.

In the area around the Lijing Gate, we discover the well-stocked emporium of the Tang Tri-Colour Pottery Museum, devoted to this acclaimed cultural product of the Tang period.

As we wander the lanes, we observe the remnants of temples, including one built by Wu for Monk Huaiyi, her lover after the death of her second husband, to keep him close to her: This was the only temple built within a palace city in the entire dynastic period of China.

The love story of Huaiyi and Wu is associated with the spectacular palace of Wu, first excavated in 1986 when its two most important sites, the Mingtang and the Tiantang, were discovered. The gilded palatial complex has been comprehensively reconstructed upon the ruins of the original edifice, which are visible at the lowest level under a well-lit glass floor.

Admission is 120 yuan, but half-price for students and those aged over 60.

We gaze down at four enormous pits, 10m in diameter and 4m deep, which used to house the mighty wooden section that held up everything that was above.

The second hall, Tiantang, was for religious ceremonies and stands at an auspicious 88.88m, the ultimate symbol of Wu's royal prerogative. Legend has it that Mingtang and Tiantang were destroyed by the same man who oversaw their construction, Monk Huaiyi.

Devastated over losing her affections to her doctor, he burntdown the palace before she made him rebuild it - and then had him killed anyway.

By Wu's time, Luoyang already had a more than 2,000-year pedigree as a power centre of 13 dynasties. In this nook of central China between the Luo and Yi rivers, core elements of Chinese culture developed.

Luoyang was also one place where neolithic seeds of civilisation sprouted as China's semi-mythical first dynasty, the Xia, linked to an excavated palace at Erlitou in Luoyang, where a new museum is set to open.

The earliest mention of Zhongguo, the Chinese name of China, dates from a Zhou-era inscription referring to Luoyang.

Perhaps a good place to appreciate this larger historical context is the Luoyang Museum, its spacious halls awash with treasures of rare significance, the biggest museum in Henan province. Admission is free and this is a place to appreciate the ancient continuity of Chinese civilisation, from Shang to Han to Tang, and to touch the lives of the past.

Luoyang's proud boast indeed is that it is home to more than 60 museums and other standouts include the Zhou Carriages Museum, where 3,000-year-old royal carriages and horses are interred; and the Ancient Tombs Museum, the largest labyrinth of dynastic tombs in China.

Beyond these highlights is a vast range of relatively obscure institutions dedicated to seemingly every aspect of the city's ancient heritage, from porcelain to the game of Go.

The area around Luoyang also has numerous profound associations with the introduction of Buddhism to China.

By tradition, White Horse Temple was China's first Buddhist temple, established around AD68 after the emperor dispatched emissaries to the West and they returned with two Indian monks bearing scriptures on a white horse.

The temple was situated just outside the walls of the Han city, but today, it is about 13km from Luoyang city, with the No. 56 bus going directly there. Admission to the vast temple costs 35 yuan.

Behind the big red gate, the Shan Men, which contains a few Han-dynasty bricks and is flanked by two white stone horses, the temple is laid out along a central south-north axis of five halls and courtyards.

Most of the current temple is of Ming provenance with a few older buildings, and the two Indian monks are interred in the courtyard.

Yanshi County, location of both the Xia and Shang ancient city sites, hosts a charming low-key and free museum of Shang-dynasty treasures.

The county's biggest draw, though, is the charming, if modest, courtyard residence of Xuanzang (602-664), the scholar-monk whose own later journey to India collecting scriptures inspired the Chinese literary classic, Journey To The West.

There is no charge for admission to Xuanzang's abode. We raise water from a well used during the great monk's time and chat with one of his descendants who, until recently, lived in the house.

Equally resonant is the nearby tomb of the great poet, Du Fu, which lay apparently neglected in the backyard of a village middle school: a lone stele in the foreground bears the poet's name and, charmingly, someone had left a bottle of Chinese spirit on the tomb.

However, for all the richness of Luoyang's historical associations, it is Wu's influence which resonates most powerfully down the ages in everything from cuisine to the city flower, the peony.

The tradition supposedly dates back to a fit of pique by Wu, when a peony refused to bloom in her presence: She furiously ordered all peonies to be "imprisoned" in Luoyang, where they would be punished with the city's harsh weather.

But they instead flourished there and Luoyang is now famous for the more than 1,000 varieties of the flower, which is celebrated in an annual festival, held from April through May.

On our final night in Luoyang, we are invited to the century-old Zheng Butong restaurant to sample Luoyang's premier culinary experience, the water banquet, supposedly designed by Wu.

The banquet has many dishes, most of which revolve around soup and all have obscure allegorical associations, which our waiting staff delight in explaining.

One highlight was Peony Bird's Nest, which comes with a curious tale about Wu being presented with a giant radish, which her chef took as a challenge to make peasant food into something the court could eat.

The dish turns radish shavings into the twigs of an illusory bird's nest and - alas, for me as a vegetarian - flavours these with pork/ chicken/vinegar.

Many water-banquet dishes drew on local culinary traditions and have now come full circle by being reinvented as street food.

The best area to explore this is the Xinghua Road Night Market, which comes alive after dark, when convoys of carts roll in with an eclectic range of foods that allude to the city's past as a capital and Silk Road trade hub.

Sit in a back alley noodle joint near Yunhe Street, once a central axis of Tang Luoyang, enjoying a bowl of Luoyang tofu soup, with the sounds and smells of the old city all around and you can almost reach out and touch the past.

And with the city bent on exploiting its potential for heritage tourism, and new museums and heritage sites opening regularly to showcase new discoveries, Luoyang's future could be as exciting as its past.

With Xian and Beijing respectively only 11/2 and four hours away by high-speed rail, and Shaolin Temple a 40-minute drive, it is worthwhile making Luoyang part of your China itinerary, particularly if you are fascinated by the legacy of this ancient civilisation's only empress.

• Harvey Thomlinson is a Hong Kong-based writer, translator and publisher who has authored China guidebooks, including Lijiang: In Search Of The Forgotten Kingdom and Luoyang: Ancient Capital.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on September 23, 2018, with the headline City of a ruthless empress. Subscribe