The Life Interview With Ching Wei Hong

Families For Life Council chairman wishes he spent more time with family

OCBC Bank chief operating officer Ching Wei Hong, who wishes he got to spend more time with his kids over his 30-year banking career, now fosters a pro-family culture as chairman of the Families For Life Council

Mr Ching Wei Hong hesitated when he was approached to head the Families For Life Council, an organisation that promotes strong families, in 2013.

The chief operating officer of OCBC Bank, who was approached by a representative from the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), wondered if he was fit for the role. His main concern: that he did not actually spend much time with his family due to his demanding job.

Though weekends and holidays were set aside to spend time with his wife and children, it was typical for the 58-year-old to leave the office after 9pm daily.

In a career in the fast-paced banking industry spanning more than 30 years, he felt as if he "could count the number of dinners" he had with his children during the work week.

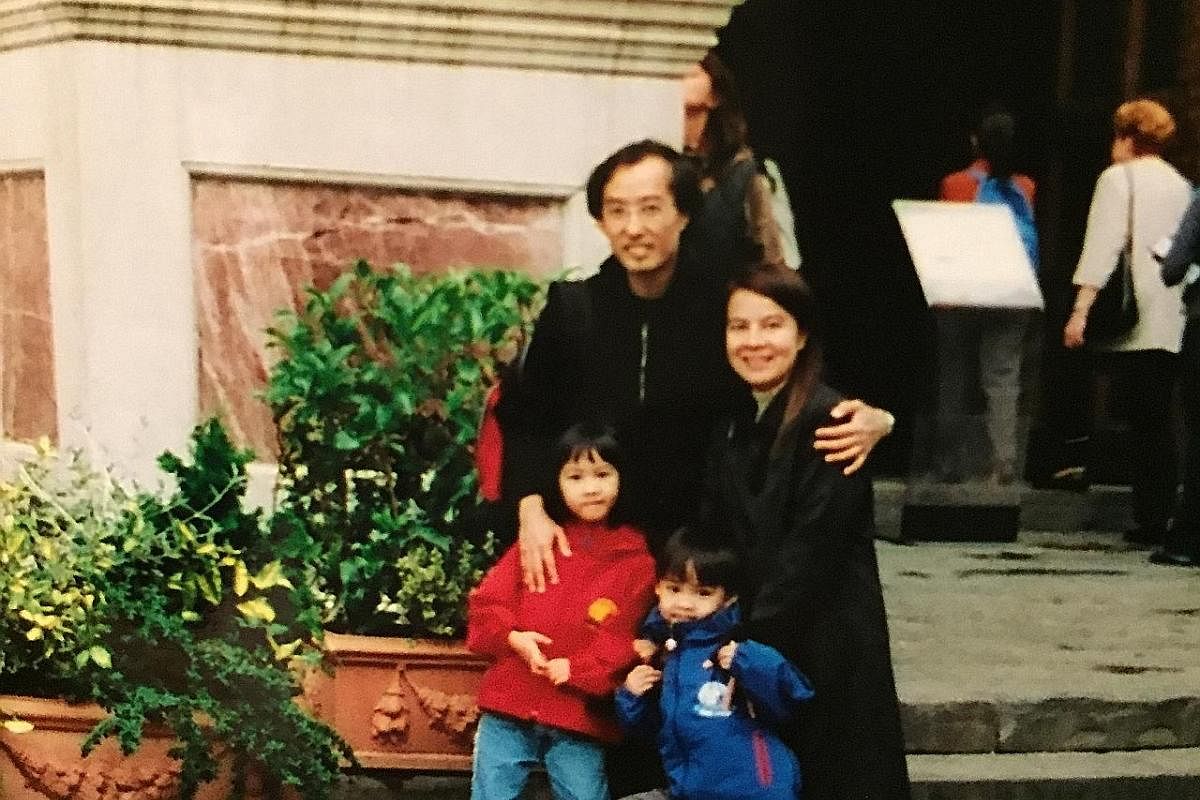

His wife Irene Oen, 57, is the managing director of a Mandarin enrichment centre. Their children are Marianne, 21, an undergraduate, and Christian, 20, a full-time national serviceman.

Mr Ching eventually took on the chairmanship at Families For Life, however, because work-life balance is a subject close to his heart.

At OCBC Bank, where he has worked for about 17 years, he encountered hard-working staff juggling multiple roles, such as a father of three who was also a foster parent, and a caregiver whose parents both had dementia.

His own commitment to being a family man stemmed from a childhood "spent pretty much on (his) own", despite having five siblings.

The Families For Life Council, formerly the National Family Council, advises and provides feedback on family-related policies to the Government. It aims to build resilient families and encourages quality family time.

The council comprises 13 volunteers appointed by the MSF and includes Mr Ching, who was recently appointed to his third term as its chairman. Since its rebranding in February 2014, it has organised programmes - such as its signature family picnics and an annual conference, the Singapore Parenting Congress - that have reached 128,000 people.

Mr Ching is the youngest of six sons - his late housewife mother's "last chance" at trying to have a daughter, he quips. His late father was a Shanghainese dressmaker who immigrated to Singapore after World War II.

"My generation had a lot less facetime with our parents," he says, tracing his resolve to do differently to his childhood.

An independent child, his parents had little spare time for him and his siblings, with whom he does not share close bonds because of the large age gap between them, he says - the brother nearest in age to him is 10 years older.

His father, Mr Ching Foo Kun, ran his own business with about 20 staff. He worked late into the night, making bespoke dresses for women in prominent families, while Mr Ching Wei Hong's mother had her hands full keeping house for a husband and six boys.

On weekends, his parents were enthusiastic mahjong players and he served beverages as a "tea boy" during their games, which lasted hours. His father lived with him and his family for 10 years until he died at the age of 100 about three years ago.

While Mr Ching is not a particular fan of the game, he used to organise short mahjong sessions to keep his elderly father occupied, using their dining table in lieu of a mahjong table and paperweights to hold down the papered surface.

One of Mr Ching's favourite childhood memories is of doing errands with his dad, when they had rare "one-on-one time" as they grabbed the bus and moved around town together with fabrics, haberdashery or finished garments in hand.

His father's drive to put food on the table for his large family influenced Mr Ching who, upon completing a business administration bachelor's degree from the National University of Singapore, decided against a further honours year as he was keen to start work and ease his father's load.

His father retired a year after the younger Mr Ching started his first job in 1983 as a Singapore-based executive with the Bank of America, where he stayed for about 14 years, taking some years off in between to work for chemical manufacturer Union Carbide and electronics firm Philips Electronics.

Mr Ching got married 29 years ago and he and his wife, who was then working at technology giant IBM, faced a domestic situation familiar to many families with two working parents.

The couple had demanding careers involving frequent long-haul travel. From the time their children were babies, they were cared for by domestic helpers.

"We had limited support as our parents were aged and I was not close to my siblings, hence my obsession now with going (beyond) three-generational families," says Mr Ching, explaining that Families For Life hopes to encourage family bonding and support within the extended family, including uncles, aunts and cousins.

He and his wife had a policy of having at least one of them at home in Singapore with their children while the other was travelling for work. He gave up the time-consuming pursuits of sailing and golf when the children were born.

Despite their best efforts to be hands-on parents, however, he says they experienced a "heartbreaking" incident when the children were both younger than three.

Neither of them was at home when a neighbour noticed that their two domestic helpers were "rough-handling" the children and notified the couple, who dismissed the helpers. The incident heightened their resolve to spend as much quality time with their children as they could, Mr Ching says, adding that employers are key to helping their workers in this respect.

In fact, when employers help staff manage their family and professional goals, this can boost workers' motivation, loyalty and performance, he adds.

"How you drive performance is not all about pushing people to work harder," he says. "We want to recognise that what happens at home has a very strong downstream effect in how people perform at work, and foster a pro-family culture within the organisation."

More than 90 companies and other organisations were involved in programmes such as allowing staff to telecommute and company family days encouraging family bonding in a recent Families For Life project between Aug 31 and Sept 3.

Mr Ching also walks the talk at OCBC Bank as part of a senior management team that has introduced family-friendly policies at the bank, which has about 8,000 employees.

In recent years, the senior management there have introduced programmes such as a career break scheme, which lets employees apply for a three-month sabbatical for any reason they choose.

OCBC Bank also has a PSLE Leave Scheme, which enables parents to carry forward up to three weeks of annual leave from the previous year if their child is sitting the Primary School Leaving Examination. The bank also has in-house childcare facilities at its Chulia Street headquarters and Tampines office.

Ms Germaine Tan, 28, an assistant vice-president at OCBC who has worked with Mr Ching on various projects in the past five years, says: "He wants to do right by his employees. He doesn't bug me after office hours and on weekends. When you have a boss like that, you have a certain comfort level."

Mr Ching's wife, Ms Oen, says they also prioritise bonding as a couple, with weekly date nights since the children were babies.

"We used to watch movies at midnight. Now we're older, it's at 9pm," she says.

During her 30-year career at IBM, which spanned most of their children's growing-up years, she had flexible work arrangements.

Mr Ching is frank about their various work-life approaches. He designated weekends and holidays as family time, while her flexi-hours meant she was part of the children's daily round for their dinner, bedtime and reading routines. She sometimes worked from home after the kids were tucked in at night.

"If I look back, the kids are closer to her today. That constant engagement (with them) makes a difference. She has a deeper understanding of their thoughts and issues," he says.

"(Work-life balance) has to be actively managed. It takes a conscious effort to plan so that important dates for the children are part of your diary without compromising your work."

These included birthdays and school competitions. During secondary school, Marianne was in the school band and Christian played rugby.

Mr Ching says: "Was that enough? There's no magical solution. I don't think I did a very good job planning."

Marianne says, however, that she is close to both her parents in different ways.

"My dad is the fun dad with whom I can hang out and do activities we enjoy, such as tennis and photography. My mum tends to be a slightly better listener, so I go to her for relationship advice."

Her father is always thinking of new things to do as a family, she adds.

On his encouragement, the children took up diving like their parents had.

Two years ago, Mr Ching and Ms Oen were there when Marianne qualified as a diver in Cebu in the Philippines, months after Christian got his diving certification in Manado, Indonesia.

In his office at OCBC Centre in Chulia Street, Mr Ching has six hourglasses that he collected during his travels over the years. They seem to be a metaphor for his consciousness as a busy parent of the fast-flowing passage of time.

He says: "School, work and values are important. There's a limited amount of time and a priority in terms of the things that I want to impart to my children."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on October 09, 2017, with the headline Families For Life Council chairman wishes he spent more time with family. Subscribe