PARIS • Was the paradigm- changing architect known as Le Corbusier a fascist-leaning ideologue, whose plans for garden cities were inspired by totalitarian ideals, or a humanist who wanted to improve people's living conditions - a political naif who was eager to work with almost any regime that would let him build?

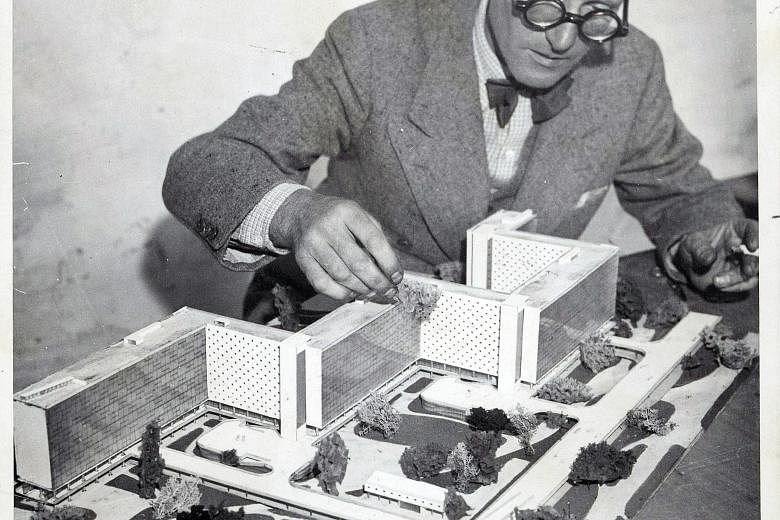

These questions, long debated by experts, are at the heart of fresh controversy in France set off by three new books that re-examine that master modernist's politics and an exhibition on Le Corbusier at the Pompidou Centre here through Aug 3, commemorating the 50th anniversary of his death.

In the light of the books, the exhibition has been criticised for glossing over, in particular, Le Corbusier's well-documented involvement with far-right elements in France from the 1920s to the 1940s.

The polemics in the French news media have grown so pointed since the show opened in April that the Pompidou announced it would hold a symposium next year on Le Corbusier's politics. The attacks also come amid the rise of the far-right National Front in France and within a broader debate on that country's World War II-era past and the legacy of modernism.

"We were very surprised by the violence of the criticism," said Mr Frederic Migayrou, one of the curators of Le Corbusier, Measurement Of Man, at the Pompidou. He said the architect's politics were well known and the museum never intended them to be the focus of the fairly modest exhibition.

It draws on Le Corbusier's post- cubist sculpture and painting to demonstrate how he used the human form as an organising principle in his architecture. But from what angle did he approach the individual?

Authors of Le Corbusier, A French Fascism, by journalist Xavier de Jarcy; Le Corbusier, A Cold Vision Of The World, by journalist Marc Perelman; and A Corbusier, by architect and critic Francois Chaslin argue that the architect's aesthetics cannot be separated from his politics, which leaned more to the right than the left, despite work he did in Moscow under Lenin.

"There's still a myth surrounding Le Corbusier, that he's the greatest architect of the 20th century, a generous man, a poet," de Jarcy said. That vision, he added, is "a great collective lie".

Some of the recent criticism has centred on a section of the Pompidou show about the Modulor, a human silhouette Le Corbusier developed in 1943, at the height of the war, as the basis for a system of proportion he used in his later work.

The show's organisers and many scholars see it as a humanist expression that helped form the basis of human-scale architecture.

"For me, it's the opposite," Perelman said. "It's the mathematicisation, standardisation and rationalisation of the body."

Born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret to a petit-bourgeois Protestant family in Switzerland in 1887, Le Corbusier was highly complex.

He built some of his largest projects in Soviet Russia in the 1930s, admired Benito Mussolini and, in 1940 and 1941, spent 18 months in Vichy, France, trying to curry favour with the fascist regime of Marshal Petain, which ultimately found his ideas too avant-garde.

During World War II, he was friendly with Dr Alexis Carrel, a Nobel Prize-winning surgeon, and had enthusiastically underlined Dr Carrel's 1935 best-seller, Man, The Unknown, which argues that parts of the French population should be gassed to preserve the most "virile" elements. Le Corbusier died in 1965.

In their books, de Jarcy and Perelman say Le Corbusier's architecture was inspired by Dr Carrel's ideas about how to clear out the old to make way for the new.

They cite his unrealised Plan Voisin for Paris in the 1920s, in which he wanted to replace the urban blight of the Marais quarter with 18 glass towers on a rectangular grid with green space.

But other scholars say the new books - which brought material previously known to experts to the attention of the broader public - have taken the most damning elements of a complex life out of context.

"Le Corbusier reflects the problems of the 20th-century temptation for radical reform," said Mr Jean-Louis Cohen, an architectural historian at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, who was a curator for, among other shows, an exhibition at the Pompidou in 1987 that addressed his politics.

"He is someone who thought reform, social change, could be made only by an authority."

But he added: "That's why Le Corbusier is interesting because of his passions and the way he crosses the passions of the century."

NEW YORK TIMES