The rise of indie furniture makers offering handmade furniture

Furniture-makers are adding unique touches to their wares with unusual materials and handcrafting

These days, when mass-produced furniture goes for a song from Ikea or Taobao, a wave of indie furniture- makers is bravely going against the grain.

The artisans insist on quality materials, craftmanship and limited-batch productions. Some of them use unusual materials such as industrial pipes, while others upcycle discarded wood to make grungy, industrial- style pieces. Most of the time, their items are unique.

The small studios breathing new life into the old- fashioned carpentry trade include The Woodwork Initiative and Roger&Sons. The Straits Times profiles three of such companies that have kept at it.

Besides more companies selling such artisanal products, there are also more places for people to learn to wield a hammer, chisel and saw.

One popular professional furniture-making course is the six-month-long Creative Craftsman Apprenticeship Programme.

It was launched in 2014 by the Singapore Furniture Industries Council (SFIC) Institute, the Employment and Employability Institute, the Singapore Workforce Development Agency and the Polytechnic of Western Australia. It is held at SFIC's carpentry campus in Yishun.

Since then, 70 Singaporeans have graduated from the programme.

Mr Neo Sia Meng, chairman of the SFIC Institute, says the growing interest in carpentry programmes comes mostly from a younger crowd.

He reiterates what every hipster millennial already knows by heart when he says: "Being in a craft-related profession gives them a sense of satisfaction and achievement when they create something different."

For hobbyists, there are also more informal ways of gaining knowledge, such as by joining online forums and watching YouTube videos to refine their skills.

Mr Greg Swyny, 36, founder of bespoke furniture- and lifestyle product-maker The Woodwork Initiative, says hands-on experience is more important than any academic degree in this field. Although his company is only two years old, he has 19 years of experience in carpentry, having learnt the trade from his father who is a carpenter and contractor.

He also conducts monthly public workshops that teach participants the fundamentals of woodworking and how to make their own wooden items such as a crate.

Mr Swyny says: "Being certified in a course doesn't mean you are the best. It boils down to your experience and how interested you are in improving your craft."

Turning trash into furniture

TRIPLE EYELID

Five deskbound years of working as an interior designer, styling homes on a computer, led Mr Jackie Tan to a crisis.

He felt "stagnant" designing interiors that he only conceptualised, but never built himself. Instead of manipulating shapes on a software, he wanted to get down and dirty with the materials and make his own furniture.

His furniture-making impulse was influenced by his time at the University of Tasmania studying environmental design.

Down Under, there is a strong do-it-yourself culture with big stores such as Bunnings selling building tools and materials. He says it is common for home owners there to build their own furniture and do up their homes.

There is also a great upcycling instinct. Mr Tan, 29, says: "Even with a piece of wood that has been thrown away, they can make something out of it. I wanted to bring that culture here."

In 2014, the bachelor left his interior design job and started an upcycling furniture company called Triple Eyelid with two former classmates at Singapore Polytechnic.

Triple Eyelid salvages materials thrown out by companies such as pallet wood and upcycles them into furniture such as stools, tables, benches and racks. It also makes some products out of concrete and pairs metal pipes with wood.

No two products are alike, says Mr Tan, who is the chief designer and maker of the furniture. Prices start at $35 for a timber amplifier.

Although he retained some knowledge from furniture-design modules he took in university, he had to brush up on his skills by asking carpenter friends for advice and watching YouTube tutorials.

The first products he added to the firm's portfolio were a daybed made of pallet wood, bookshelves from crates and tables fashioned out of old cabinet doors.

The company's location then, a workshop space in Woodlands, was ideal for scavenging as it had a lot of discarded wood. "In the first year, I never ran out of material," he says. "The industrial area was like a shopping centre. I pushed my trolley around and filled it with wood."

Triple Eyelid got its big break when owners of Rabbit Owl Depot cafe in North Bridge Road asked the studio to make its furniture. The project, which included tables and benches, raised the company's profile.

Although Mr Tan gets a good stream of orders now, training himself to be a carpenter was not easy. The usual splinters and cuts aside, he broke out in acne from being exposed to too much dust.

He says the design and building is also filled with trial and error. Once, a concrete stool he made for the cafe broke after a customer sat on it. He realised that the concrete mix he used was not strong enough. Since then, he has improved his quality checks for the furniture he makes.

In 2015, the two partners left the business. He now runs Triple Eyelid on his own.

He has partnered Xcel Industrial Supplies, a company that supplies industrial packaging products.

It provides him a space in its Joo Koon warehouse and supplies him with old reclaimed pallet wood it no longer needs. Mr Tan also gets to work with bigger machines such as panel saws and a standing drill press. He does not pay rent, but shares some of the profits with Xcel.

While Singapore's indie woodworking community is still small, he is happy to see more people trying to make a living out of it.

"I'm proud there are more people starting their own business. It's not a competitive scene and I try to help fellow crafters and share knowledge. There's a sense of accomplishment when you make things with your own hands."

Creating only bespoke wooden pieces

EVERYDAY CANOE

Most nights, Ms Ng Xin Nie stays in her room listening to music and carving small wooden objects. These could be spoons, animal- shaped brooches or mini vases in the shape of houses.

The pieces are sold under Everyday Canoe, a small woodware accessories business she started in 2013. The goods are not sold in stores, but made to order. Prices start at $30 for a customised brooch.

Woodcraft started as a soothing hobby for the 28-year-old, who is single and also works as an illustrator.

While her illustration work is done on the computer, she says she can "switch off and work on something analogue" with her chisel and gouge.

She made her first wooden object when she was studying industrial design at the National University of Singapore. For a design course where she was tasked to redesign an everyday object, she chose to remake a rice scoop in wood - a change from the regular plastic products in the market.

She loved the experience, but never got to be as hands-on with wood after she graduated.

Her first job out of school was as a designer at a furniture company, where all of the sketching and modelling of furniture and homeware were done on the computer.

However, while the prototypes were being built, she spent some time with carpenters in the workshop. "(That experience) made me realise there's also a gap between designer and maker."

After two years, she left her job and thought about what she would enjoy doing every day. "The answer was woodworking and illustration," she says. "That university project stuck with me all this while. I still have the prototype. I didn't want to leave industrial design completely."

That was when she started Everyday Canoe, a name that reflects her "journey with woodworking".

To hone her woodworking skills, she watches YouTube tutorials and reads specialist forums.

A friend whose family runs a carpentry business provides hardwood offcuts such as teak, cherry and maple wood. She says: "These pieces are too small to make into bigger furniture pieces. If I didn't use them, they would just be binned."

Everyday Canoe started as a hobby, but after positive responses from friends and shoppers at a Christmas market, she decided to take orders.

Her work has a refined minimalism. Each piece may look simple, but a lot of work goes into it.

For example, crafting a single spoon is a labour-intensive process that takes about 10 to 12 steps.

She starts with drawing the general shape of the spoon on a larger piece of wood and cutting it with a bandsaw. She does this in her office because the saw is noisy and may disturb her neighbours.

At home, she uses a gouge to hollow out the well of the spoon and then a carving knife to sculpt its silhouette and soften its edges.

When she is happy with the form, she sands the spoon down. The final step is a coating of food-safe oil to protect the wood from moisture.

Those who are keen to try out the process can attend one of her workshops, which are conducted at Itchy Fingers, a studio-workshop space in Jalan Besar, at least once a month. It costs $140 a person for a class on how to make a dessert spoon.

She has no plans to mass-produce her pieces to be sold in stores, preferring instead to discuss the design of each customised piece with her clients. "Then I deliver something that I know someone will have for life," she says.

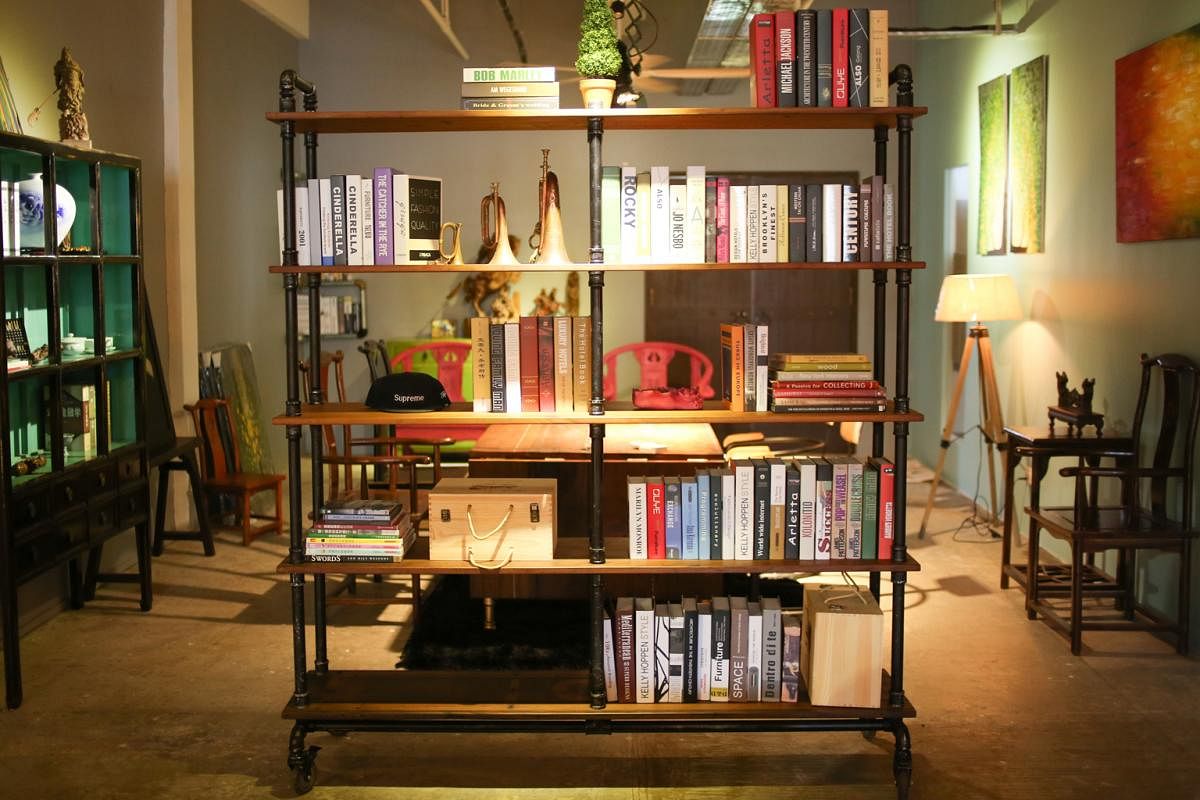

Industrial pipes are his signature

PENG HANDCRAFTED

For a friend's housewarming gift five years ago, Mr Bernard Peng built a 1.7m-long wooden dining table with industrial steel pipe legs.

With the help of a carpenter friend who had the necessary tools, he assembled the pipe legs and worked on sanding the wooden table top and coating it with a natural oil.

Visitors to his friend's home were suitably impressed. They started commissioning him to make furniture for them.

Soon, they were bugging him to put his work on social media so others could find the elusive designer easily.

He finally set up a Facebook page in 2014 and the positive reaction was overwhelming. He received more than 10 calls a day, with many others dropping him texts and private messages on the site.

Mr Peng, 43, whose Facebook page now has about 41,000 likes, says: "I just built a table for a friend. I never expected it to be so popular."

In 2015, he launched Peng Handcrafted officially. He also owns a niche retail business selling replica armour, guns and swords.

At Peng Handcrafted, he works mainly with industrial pipes, incorporating them into tables, dividers, chairs, shelves and lights.

Other materials he uses are American white oak wood and timber salvaged from the wooden beds of scrapped lorries.

He has grown up around pipes as his family business deals with sprinkler pipes. There, he learnt to join the pipes so that they line up correctly.

Mr Peng, who is married and has a three-year-old daughter, says: "Even though I'm not trained as a designer, I work well with technical things."

While he started out alone, he now has two designers working with him.

His design process does not involve any fancy drawing programmes, but the humble Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

In his office in Bendemeer, he maps out the dimensions of each piece on the computer.

His team of four other workers helps him build the designs in a Kaki Bukit workshop.

Bigger pieces are dismantled into smaller parts before they are re- assembled in a client's house.

On average, a client can get his order in about three to four weeks. Mr Peng works on only one order at one time.

A light fixture goes for $80 while a shelving system starts at $1,200.

He is all about experimenting with materials to build better products. For example, if a particular castor wheel does not fit a pipe opening used as a leg for a table or bench, he would try different models or modify the pipe.

He prides himself on not welding or nailing pieces together.

"That's an easy way out," he says. "I believe in the 'marriage' of hardware, rather than just forcing them together."

Clients have come to him with interesting requests such as fitting an iPhone dock or light fixture into a shelf, which he has managed to incorporate into his designs.

Mr Peng, who has made products for Housing Board showflats, has had many learning moments.

Because many of his clients live in high-rise apartments, pre-assembled parts have to fit into lifts.

Once, he and his workers had to climb up 19 storeys with shelves - the parts were still too big for the lift because of his miscalculation.

Constantly learning, he refers to non-furniture sources such as car or graphic design magazines to get inspiration.

"I don't see myself as a designer, but rather a problem-solver who helps people get the right furniture for their homes. The satisfaction, for me, comes from the smile on a customer's face."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on February 04, 2017, with the headline The rise of indie furniture makers offering handmade furniture. Subscribe