NEW YORK • In the ever-raging battle between faith and science, neurologist Jay Lombard is one of those rare emissaries who communicate in the language of both camps.

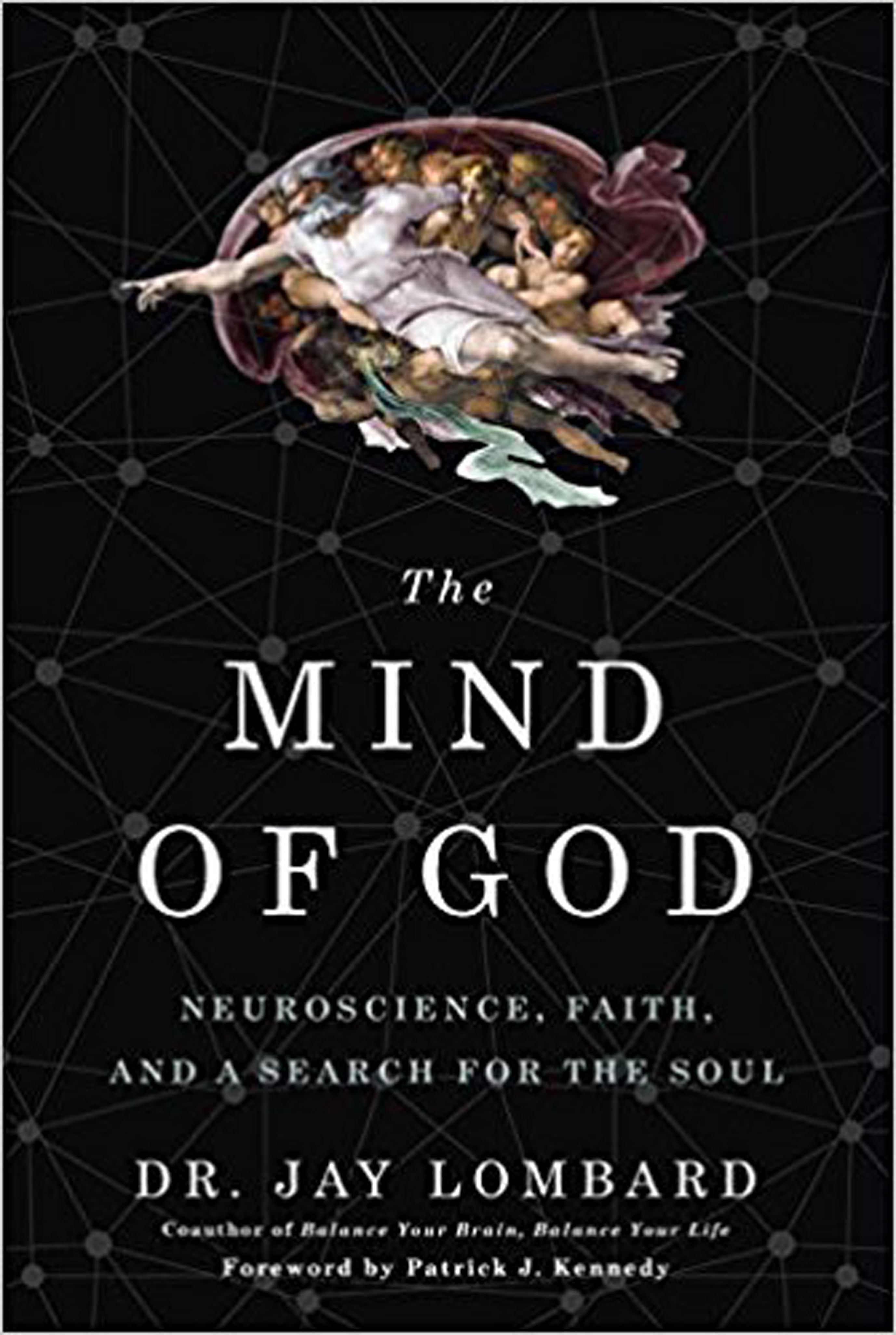

In his new book, The Mind Of God, he uses his experience studying the brain to ask some of the largest philosophical questions: Does God exist? Does life have meaning? Are we free?

Lombard writes that he is interested in a "large faith", rather than a specific religion - "a faith invigorated and enlightened by science rather than being at odds with it". Below he discusses the debates over brain and mind, his editor's unpromising reaction to an early manuscript, his appreciation for musician Jerry Garcia and more.

When did you first get the idea to write this book?

When I was in full-time clinical practice and some of the most unusual cases seemed to find me, these bizarre cases that made author and neurologist Oliver Sacks' look mundane.

The first part of the process as a neurologist is to figure out the anatomy and structurally where the origins of behaviours come from. That's the first dive. But from there you ask more fundamental questions about the brain and mind and where they interface.

Trying to find the biological origins of psychiatric disease is much more difficult than for a stroke, hypertension or ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a progressive neurodegenerative disease). But it's there.

And you see that no matter how reduced you get, you're left with sand going through your hands. That took me to a completely opposite place, which was to ask questions about purpose and meaning; about suffering and about how patients themselves make sense of their suffering; and about how I make sense of it as a clinician.

I wrote a screenplay about it, a tragicomedy I still have in my drawer somewhere. It was my first attempt to make sense of it.

What is the most surprising thing you learnt while writing it?

How much we are dependent on our own brains for whatever form of faith we experience in our lives. How reliant we are on the physical aspects of our spiritual being.

What I learnt personally is that neuroscience is totally wrong. Neuroscientists don't believe that such a thing as the mind exists. They flat-out reject the concept of mind. I find that a very scary, slippery slope. I think psychiatry has lost its mind, both literally and metaphorically. A lot of the book is about that part of our brain that connects us to our deeper, spiritual underpinnings. It's not our rational brain; it's our narrative brain.

Mainstream psychiatry is really just: symptom, check, this is the right medication for you. We don't do therapy anymore as psychiatrists. If you need that, go to a psychologist. It's kind of ludicrous. You're taking care of people's minds, but you don't want to know anything about the mind.

In what way is the book you wrote different from the book you set out to write?

The whole first version of the book, a 400-page manuscript, was thrown out by Random House. I thought it was great. My editor, Gary Jansen, forced me to really understand the content of what I was trying to do and how to explain it to others, whereas the first version of the book wasn't concrete enough for people to grasp - even though we're talking about something that is fundamentally not concrete: spirituality. So it was a big challenge.

The question Gary had for me was: "Does neuroscience prove there's a god?" I said, "Really? You want me to try to answer that?" And the second question was, "Does it prove there's an afterlife?" I said, "What do I know? You've already given me the advance. Can I give back this money?" He asked me, "Do you know what you're talking about?" And I started laughing, and said, "Does anybody know?"

Who is a creative person (not a writer) who has influenced you and your work?

Jerry Garcia from the Grateful Dead. He wasn't the greatest virtuoso guitarist, but he created such beautiful music. I've always wanted to express myself as a writer, all through my life. And there are a lot of writers I take inspiration from - such as Milan Kundera, but from Garcia I took the idea that you can find art and beauty in imperfection, and true art is from your soul.

My daughter is 15 years old and she loves the Grateful Dead. How is that possible? It's like, "You're a Deadhead? Oh, that's genetic. We'll find a gene for being a Deadhead."

And the rabbi in college who stopped me and asked if I was Jewish. I had never stopped to consider that and, 40 years later, I still have a relationship with that person. He's the living version of Job. He's gone through the most catastrophic events of anyone I've ever known, and his faith in God is completely unshakable.

Persuade someone to read The Mind Of God in fewer than 50 words.

I believe we are living in a time of huge existential crisis in our society. I want people to ask themselves, first and foremost, if they have a sense of purpose. If they say yes, but they don't know what it is, they should read the book.

NYTIMES

•The Mind Of God: Neuroscience, Faith, And A Search For The Soul is available on Amazon.com