Full disclosure: I was involved in this production, quite by accident. I was seated in the third row. Actor Lim Kay Siu surveyed the audience, pointed at me, and summoned me on stage for my Fringe Festival debut. Another disclaimer: while I will do my best to avoid major spoilers, this review will contain them, and I would advise those who have not seen White Rabbit Red Rabbit, or who plan on watching it, to save their review-reading for after the show.

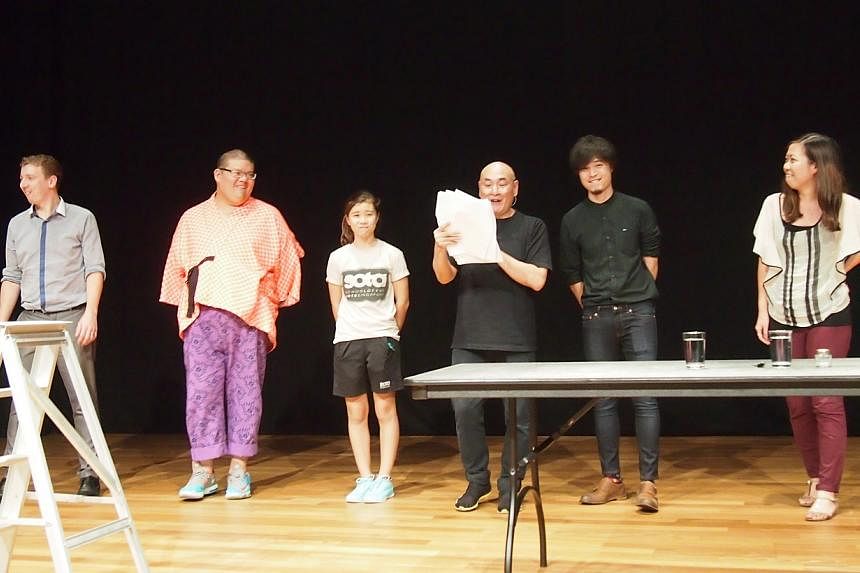

The facts are these: Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour, who was 29 at the time of writing this play about five years ago, does not have a passport and cannot leave his home country. The sole actor literally receives the script only when he steps on stage for the performance. Festival manager Jezamine Tan brandishes the script in a sealed envelope at the audience in the Esplanade Recital Studio before gleefully handing it over to Wednesday evening's performer, seasoned actor Lim Kay Siu.

What starts out as a bit of playful mischief, an Aesop's Fable-type story about animals in a circus, turns into a rabbit hole of layered meanings and intentions - some gimmicky, some moving and profound. Rabbit is as much a treatise on censorship and constraints as it is a dissection of performance and the theatre.

Sure - meta, self-referential theatre is hardly a new device, and neither is confronting the audience nor cajoling them into participating. But so much of the excitement of seeing live theatre lies in the unexpected; there is a frisson of delight when something goes wrong and an actor has to ad-lib, or when a well-timed plot twist kicks in. Rabbit takes this to the extreme, setting the stage for an actor to confront an audience at his most vulnerable, and that sense of being on one's toes does transfer to the viewer.

Soleimanpour constantly, and sometimes frustratingly, darts ahead of the audience, trying to pre-empt their doubts and any smidge of cynicism ("this (spoiler; redacted) is probably fake because it's the theatre", he remarks at one point), but he does so with such charming self-deprecation and such wistfulness that the actor, reading his script fresh off the page, inadvertently channels the first emotion that surfaces, and one cannot help but sympathise with him.

Is it terribly narcissistic to expect an audience to welcome you and to engage with you? Soleimanpour offers his e-mail address to us at one point, and then plaintively and movingly asks if we can save a seat for him, in the front row, to 'watch' a play he might never be able to see for himself.

Some points are belaboured and there are moments where Soleimanpour seems to be throwing in devices to sustain the trick on which this play is built, to keep the rhythm of the show going, to distract and to entertain. But Lim soldiers through the script quite impressively; he has a generous, engaging presence and the audience warms to him quickly after a few sets of what could be described as 'warm-up' interactions.

The play can be as manipulative or as permissive as the audience and actor makes it out to be - we are free to leave at any time, actor included, and yet we stay. Soleimanpour reminds us of the spectre of an oppressive regime in Iran: when Lim says "this is not in the script", one is never sure if they are his own words, said of his own free will, or if they are actually scripted.

Is it particularly "Singaporean" that the audience on Wednesday night wielded power that it did not exercise, dutifully following Soleimanpour's scripted instructions? I understand from friends abroad that, in one instance, audience members intervened to prevent an actor from doing something. The playwright almost rubs his hands in glee at having made an audience member make another audience member do something, exerting a grip over his spectators while completely absent from the room.

This travelling play, which has journeyed from the United Kingdom to Australia and now to Singapore - it was also staged at the National University of Singapore Arts Festival last year - has become a metaphorical passport for its playwright. It cannot be staged in Iran, so it goes elsewhere. There is something startlingly familiar about Iran's mandatory national service for men; if Soleimanpour had been a Singaporean who refused to do his national service, would we be reacting in the same way to his play, with such fervent excitement? Or would he be labelled unpatriotic and a coward?

Soleimanpour wonders, through the conduit of the actor, if the police in the country of performance even care about what happens in the theatre. Perhaps it's good that they do, because it means that theatre still has its power.

book it

WHITE RABBIT RED RABBIT

Where: Esplanade Recital Studio

When: Jan 22 (featuring Pam Oei), Jan 23 (featuring Benjamin Kheng) and Jan 24 (featuring Karen Tan) at 8pm

Admission: Very limited tickets at $22 from Sistic (call 6348-5555 or go to www.sistic.com.sg)

Info: www.singaporefringe.com