Nobel laureate in literature Herta Muller writes predominantly in German, although she is fluent in both German and Romanian. But she has admitted that she would never translate her own work from one language to the other.

In a 2012 speech, she honoured her translator Radka Denemarkova, saying: "The art of translation is looking at words in order to see how those words see the world. Translation requires an inner urgency that will make that which is different as close to the original as possible. Finding this eye-to-eye contact is extremely difficult. It is a great art."

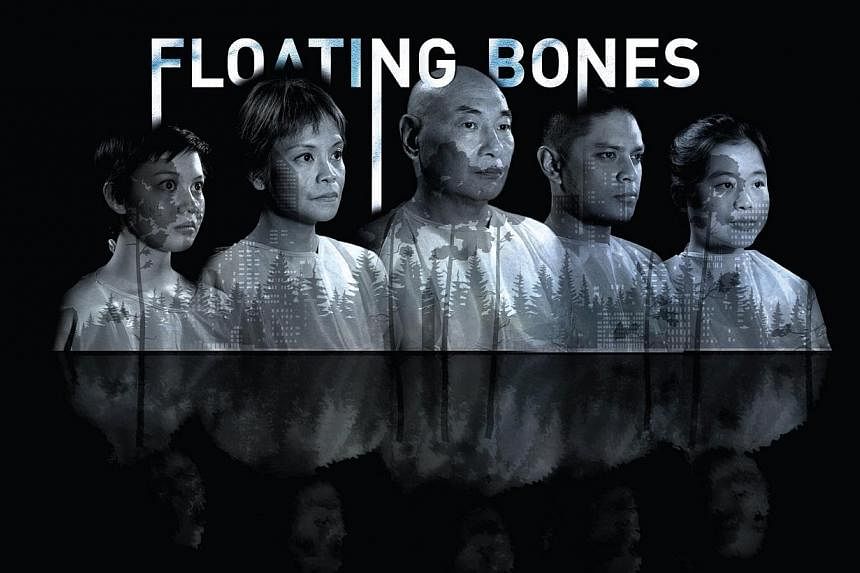

I was reminded of Muller's words during last Friday's performance of the double-bill Floating Bones, which featured two short plays by Singaporean playwrights translated from the Chinese to English, and performed on stage as such for the very first time.

It was a disquieting and lyrical evening of lush imagery and dark, dark humour, featuring Quah Sy Ren's Dragon Bone (2001), where the stories of a fugitive refugee and a young boy experiencing sexual awakening intertwine in an endless cycle of guilt and violence; and Han Lao Da's Floathouse 1001 (1995), a dystopian vision of the future where people are cast off on floating pods because there is no more room on land. The minimalist set-up of The Arts House Play Den becomes a sort of purgatorial wasteland for all these characters, each trapped by their motivations and circumstances.

Both Han and Quah are influential and prominent playwrights in Singapore's Chinese-language theatre scene, and through the thoughtful cadences of translator Jeremy Tiang - as well as other creases smoothened out during rehearsal with the actors and director - the subsequent result in English barely betrays any of the seams of translation, the frayed edges when one makes the journey from one linguistic framework to the next.

In translation, there are often awkward turns of phrase and an abundance of concepts that are difficult to pin down. Han's Floathouse 1001, for example, is rich in language-specific puns that are near impossible to capture as accurately in any language other than its original Chinese.

In this case, the creative team has taken the art of translation a step further into an act of adaptation, altering both the endings to the plays and choosing to adhere to the spirit, rather than the letter, of the works. While puritans might cry foul, I found this exercise in adaptation to be both respectful and sincere, gamely tackled by director Elina Lim and a generally strong cast. The language unfurls naturally, and the actors never have to struggle with clunky, over-literal words or phrases, which then allows them to flesh out their characters more meaningfully.

With its stream-of-consciousness monologues and lurid images of white, bleached bones, Quah's Dragon Bone felt a little more like an abstract diorama to be viewed and admired from a distance, its figures of the ever-fleeing refugee (Bridget Lachica) and boy (Lim Kay Siu) more like concepts than characters.

Young actresses Bevin Ng and Elizabeth Sergeant, while both commendably committed to their roles as strange, wordless spirits, were sadly rather extraneous - even distracting. They vaguely re-enacted the evocative imagery of Lim Kay Siu's monologues, which would have stood well enough on their own without filtering them through yet another layer of obvious symbols.

Han's Floathouse 1001, on the other hand, dove deeper into the lives of its three characters stuck on a floating pod. As the Floathouse is rocked both by unruly waves and their own insecurities, their not-so-secret fears of death and deep-seated regrets rise quickly to the surface when they realise that the end is near.

Sergeant is especially gripping (and well cast) here as an android woman, and the trio of Lim, Lachica and Zachary Ibrahim play off each other well, bringing Han's remarkable ear for dialogue to the fore. Han, a seasoned writer of xiangsheng (Chinese crosstalk) plays, has an illuminating grasp of banter and debate, as he wrestles with ideas of mortality and scientific ethics (regaining youth, reversing time) without ever feeling didactic.

There is a certain beauty to seeing three levels of creation unfolding at once: the core of the playwrights' original scripts, their new lives in English, and the most visible layer of the cast and director's interpretations of the text.

Nelson Chia's Nine Years Theatre is doing strong work in translating and adapting Western classics into Chinese, and I think Floating Bones is another sign of how the process can continue to knit together Singapore's abundance of linguistic and cultural influences.

Follow Corrie Tan on Twitter @corrietan