AUTOBIOGRAPHY

ON THE MOVE

By Oliver Sacks

Picador paperback/397 pages/$34.95 with GST from Books Kinokuniya or on loan from the National Library Board under the call number English 616.80092 SAC-[HEA]

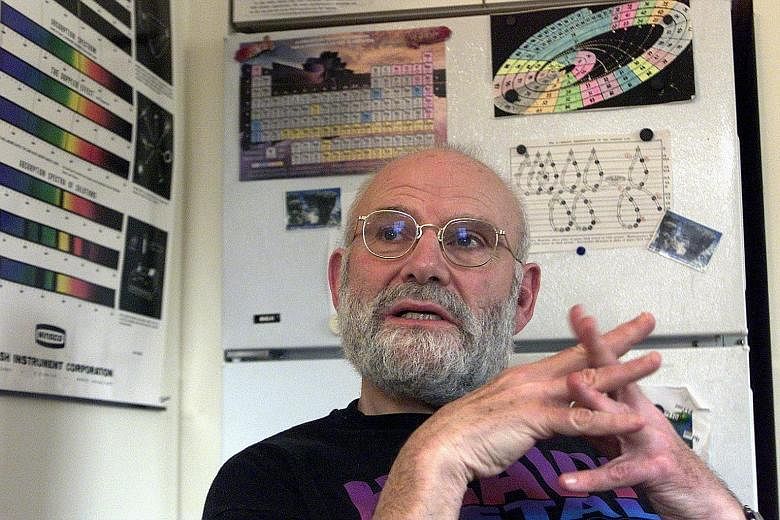

British-American neurologist and author Oliver Sacks, who died aged 82 on Aug 30, liked to say that he lived "a certain distance from life", with all the "selfishness" and "self-absorption" that it brings.

That view might surprise the many fans of his books, notably Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat and An Anthropologist On Mars. All of his books are shot through with compassion.

His earliest, 1970's Migraine, had Booker-winning British writer Hilary Mantel hailing him as her hero. Mantel, whose headaches were so bad that she found it hard to see or hear, said Sacks' book gave her so many insights into her ailment that she found the will to overcome it, eventually writing the much-lauded Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies.

As she wrote in The Guardian in February 2013: "Informed by 25 years of hospital experience, he sees the soul within the symptoms."

The first thing you need to know about Sacks' latest and last book, On The Move, is that it dwells largely on his struggles with himself and so there are only glimpses of his greatness in alleviating the suffering of his patients, whose brains have developed or been injured such that they, say, cannot see colours, are conscious but unable to move a muscle or whose bodies jerk and shake without warning.

On The Move continues where he left off from his 2002 autobiography, Uncle Tungsten. After his boyhood, which he and his elder brother Michael spent at a dour boarding school run by a sadistic headmaster, Sacks grew up juggling many intellectual passions, chief among which were writing, chemistry and marine biology.

When he was 12, a teacher wrote in his school report: "Sacks will go far if he does not go too far."

The youngest of four sons of two revered doctors, he went up to Oxford at the age of 23 to study anatomy and physiology to prepare to emulate his parents. By then, he knew he was homosexual and had to hear his mother, gynaecologist Elsie Landau, call him "an abomination".

He had been her favourite son but after he confessed to being gay at the age of 18, she told him: "I wish you had never been born."

The second thing you need to know about the book is that he revelled quite a bit in machismo. He would do things like ride about 1,600km around California on his motorcycle every weekend, take part in weightlifting championships and surf the waves so avidly that he once dislocated his shoulder.

The hedonistic bubble he lived in outside of work soon burst when his work responsibilities got heavier. None of that was leavened by love, though, as he recoiled from a string of failed relationships. After his fourth break-up, he said, he stayed celibate for 35 years, finding true love only at the age of 77, which helped him endure cancer of his right eye.

For 70 years before that, he mused, he was fighting fit.

But, it is humbling for the reader to learn that, throughout, this titan of knowledge lacked "intellectual self-confidence" and took to drowning his sorrows in drink and then drugs. Then he found a better outlet - in writing.

"In those rare, heavenly states of mind," he said, "I may write non-stop until I can no longer see the pages."

The most wrenching parts of this memoir deal with his elder brother, Michael, a schizophrenic.

Sacks' sibling was bullied and beaten regularly from the age of 13 in boarding school, and he soon developed the psychosis. Sadly, Sacks' response was to flee Britain for the United States.

Despite having what he called "a passionate sympathy" for Michael's suffering, he said: "I had to keep a distance also, create my own world of science so that I would not be swept into the chaos, the madness, the seduction, of his."

The reader can only imagine how that abandonment hit Michael; both brothers had weathered World War II together.

Michael died before Sacks, after holding down a simple, steady job till the age of 56.

One of the book's few points of light comes when we learn from Sacks that even beleaguered Michael found a way to give back to others, by being a "virtual encyclopaedia" whom those in his nursing home would consult, after years of reading the books that Sacks sent him regularly.

Perhaps the most winning quality about Sacks' brutally honest book was his consistent willingness to consider the points of view of others, especially those who had hurt him deeply. For example, he said that his mother's utter disgust with him was "the anguish of a mother who, feeling she had lost one son to schizophrenia, now feared she was losing another son to homosexuality".

He continued writing long, loving letters to her until her death in 1972. That was entirely in keeping with his warm, slow-burning and empathetic nature, which the late actor Robin Williams played so well in the 1990 film of Sacks' book, Awakenings.

In the end, as this book shows, Sacks' most bewildering patient was himself, but with all his contradictions, he proved to be one who really understood what it meant to be fully human.

Here are three of many take- aways from this book:

• Do not call anyone "mentally ill"

While this may be factual, convenient shorthand for those suffering from brain ailments, using that phrase on someone usually guarantees that he will be treated as a source of bother, and not a human being, in the health-care system.

• Rethink the use of tranquillisers

Sacks saw from observing his brother Michael that such supposedly calming drugs actually sapped a person of hope and purpose and so should be used sparingly, if at all. Otherwise, those popping the pills would wind up even more depressed than they already were.

•Distrust mechanical, clinical healthcare systems

Sacks said the best care was to give a patient an environment that was as understanding and comforting as his own home, such as the residential "manors" of the Little Sisters of the Poor, which he supported for 40 years.

Just a minute

The good

1. The late American neurologist Oliver Sacks' last book is suffused with compassion, yet his brand of human kindness is not cloying. He disarmed personal and career demons with warmth and a willingness to listen to, understand and comfort his patients and loved ones.

2. Better yet, he paid detailed tributes to the many experts in various fields who showed him how best to alleviate suffering. You will learn from the greats who taught him how to put people at the heart of all your endeavours. For example, Sacks recalled the British psychiatrist R D Laing urging everyone to see schizophrenia not as a disease but, as Sacks puts it, "a whole, even privileged, mode of being". That is akin to seeing the Dustin Hoffman character in the 1988 movie Rain Man not as a mumbling nutcase, but an inspiring genius.

3. Fans of the poets W. H. Auden and Thom Gunn will enjoy fresh insights about their literary heroes, as Sacks recalled his long friendships with them in this tome.

4. He used footnotes cleverly. He tucked the technical bits about his patients' afflictions under these. The result is an unthreatening series of capsule-sized references that enlighten, rather than put one off the niceties of science.

The bad

1. In his lifetime, Sacks had more than 1,000 diaries and letters. The drawback to having such a rich trove is that he was able, and indeed wont, to chronicle every year of his life since World War II. So, at page 169 in a 384-page memoir, readers are still with Sacks circa 1966. This makes the book a curious case because while his prose is terse, clear and smooth- flowing, you will likely find reading it rather a plod.

2. While he was an avid chronicler, he was less concerned about chronology in this book. He darted about the decades of his life throughout the book and often within chapters. As each chapter's theme is not immediately discernible, readers will sometimes find his narrative disorienting because he cuts fast and loose with dates.

The iffy

1. Even allowing that it is a memoir, two-thirds of this book is navel-gazing, if often quite moving.

FIVE QUESTIONS THIS BOOK ANSWERS

1 Why might failing your examinations repeatedly not make you a failure?

2 Why is resilience a journey and not a goal?

3 What sort of people might best work well together?

4 Why is pain so hard to bear?

5 Why should you never label anyone as being mentally ill?