CANNES (Reuters, NYTimes) - French cinemas were right to object to Netflix' appearance at Cannes, the film festival's director said on Tuesday (May 16), ahead of the competition that this year has been marked by a fight between the theatres and the American streaming giant.

Netflix, which streams films and television shows to subscribers, has two of the hottest movies in contention for the Palme d'Or - its first time in competition at the festival.

But, in a country where movies shown in cinemas cannot be streamed for three years, Netflix refused to arrange distribution across France - meaning Okja, starring Tilda Swinton and Jake Gyllenhaal, and The Meyerowitz Stories, starring Ben Stiller and Dustin Hoffman, will not be seen on the big screen after their Cannes premiere.

The outcry from French cinemas was such that there were rumours that the two Netflix movies would be excluded at the last minute.

That has not happened, but the festival has tightened its rules so that in future any competition film will have to get a French theatrical release - effectively barring Netflix after this year.

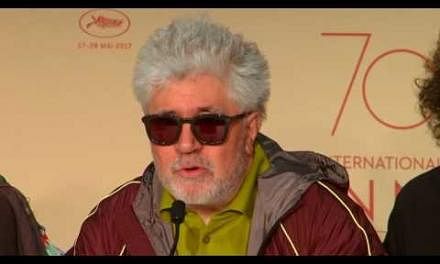

"Cannes is a film festival in theatres, and, for the territory of France, we would like to have all the films competing in Cannes available in theatres," festival director Thierry Fremaux said in an interview. "Netflix decided to go first via the internet, so French theatres protested, and they are right, because cinema is first of all in theatres."

At the heart of the Cannes-Netflix clash is what's known as the French cultural exception, a law that requires a percentage of all box office, DVD, video on demand, television and streaming revenues to be pooled to finance homegrown films and help finance foreign films. The law also mandates a 36-month delay between theatrical release and streaming date. Netflix has not wanted to participate in the French system, and that offended some in the film industry here.

"They are the perfect representation of American cultural imperialism," said Christophe Tardieu, director of the National Cinema Centre, known as the CNC, a state entity that coordinates public financing of films. It also underwrites more than half the budget of the Cannes Film Festival and has seats on its board, as do French movie theatre owners.

"I deplore Netflix's attitude in this affair, which showed total intransigence and refusing to understand and accept how the French cultural exception works," Tardieu added.

In contrast, another streaming company, Amazon Studios, says it aims for theatrical releases for its films. It has a film in competition at Cannes this year, Todd Haynes' Wonderstruck, which will be shown in theatres in France.

"Cannes misjudged," said Thomas Sotinel, a film critic and journalist at Le Monde. Festival programmers thought "they could get away with showing Netflix movies", he said. "But they found out Netflix wouldn't move, and at the same time they were reminded that on the board of Cannes sit people like the theatre owners, who don't want to budge either. So they were caught between those two very immovable protagonists - or rather, antagonists."

Netflix has not responded to requests for comment but CEO Reed Hastings said on his Facebook page: "The establishment closing ranks against us." He added that "Okja" was an "amazing film that theatre chains want to block us from entering into Cannes film festival competition".

Fremaux said the Netflix titles were short-listed for their artistic merit, "directed by two directors who are real movie guys": South Korean Bong Joon Ho and American Noah Baumbach.

The Cannes rule change has also revealed fault lines within the French film world. While the president of the National Federation of French Cinemas last week said the festival had been "taken hostage" by Netflix, the Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers said in a statement that the Cannes flap was just a distraction from the "inertia" that had led to the breakdown of talks.

The French screenwriters guild on Tuesday issued a statement supporting Baumbach and Bong, saying the controversy had "the benefit of putting back on the table" the unresolved discussions. "There are idiotic rules that don't let Netflix films come out for 36 months; I understand it's complicated," said Pascal Rogard, director general of the authors' society. "The real open question that will be given to the next culture minister is, 'Can we create a modernised media chronology so a film doesn't have to wait three years to go to Netflix?'"

When asked whether Cannes risked missing out on new ways of movie-making, Fremaux said he wanted to talk about the movies, not the "Affaire Netflix" which has grabbed the headlines. "The festival is always changing and is always the same," he said. "The only thing, as we are talking about movie theatres, is that at a certain moment in the day, several times a day, the lights go out and we watch a film - together - and that's cinema."