Dane DeHaan is an actor with a baby face, but with eyes that look transplanted from a far older, more angsty man. It's a quality he's used in roles that call for fragility or mental illness, or both.

In Life (M18, 112 minutes, opens tomorrow, ) he uses his eyes to give his portrayal of James Dean its James Dean-ishness, while not leaving out the furrowed brow and high-pitched voice.

The actor hits a bull's eye on Dean's mix of childlike vulnerability and adult cockiness, even if he looks the least like the long-deceased actor among those who have tried, such as James Franco and Casper Van Dien.

Screenwriter Luke Davis relied on published work and his own interviews with witnesses for the timeline and dialogue.

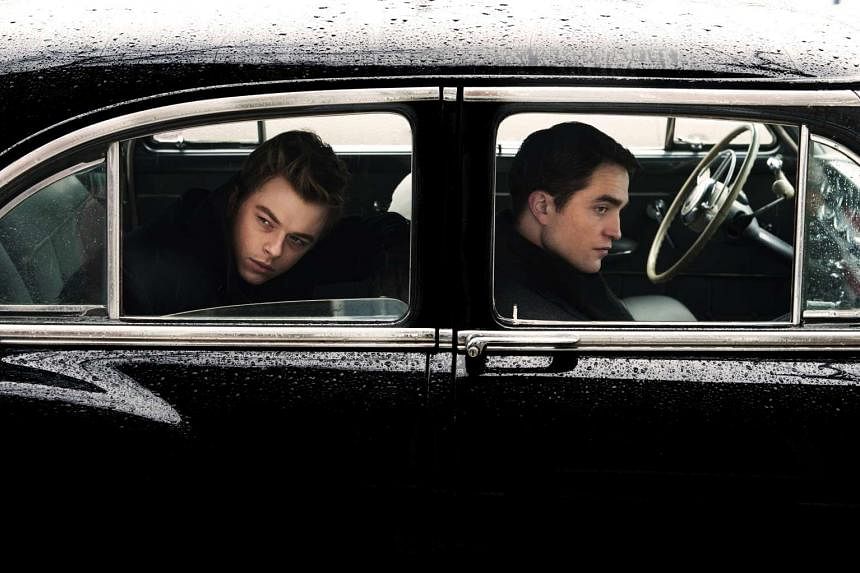

The story starts in the months leading up to his big screen debut in East Of Eden (1955). Photographer Dennis Stock (Robert Pattinson) needs a subject. He is struck by Dean's talent and pitches Life magazine editor Morris (Joel Edgerton) the idea of a photo essay on the young actor. The editor accepts, but Stock is taking a gamble: He has yet to secure the actor's permission. Even if the actor agrees, the photographer still has to put up with Dean's flightiness.

History tells us Stock got his pictures. His shot of a hunched Dean in a raincoat in mid-stride on a wet Times Square is today closely associated with the actor. Dean died in a car crash in 1955, a few months after it was taken.

You don't cast an actor with Pattinson's star power in a supporting role. His character of Stock is a counterpoint to Dean - the photographer is as tied down to responsibilities as a breadwinner as Dean is free of them, and the actor's contempt for career ambition, or even showing up for agreed-upon meetings, is a source of fascination and frustration for Stock.

That two-hander structure of poet versus salaryman can feel stagey, but director Anton Corbijn (The American, 2010; A Most Wanted Man, 2014) edits with care, taking pains to not overstate the contrast. Appropriately, Corbijn's career began in still photography, rising to fame on his sessions with U2 and Joy Division.

He elicits wonderful performances from DeHaan, Pattinson and also Ben Kingsley, who steals every scene as studio boss Jack Warner. Kingsley's mogul cajoles, flatters and threatens, all in the space of two or three lines. Dean could easily have come across as insufferably self-righteous when it came to the purity of his art, but DeHaan and Corbijn balance the sanctimony by showing that the actor was capable of the occasional act of hypocrisy.

'Tis the time of the year for the Oscar contender, as the biopic Life proves. So does Suffragette (PG13, 107 minutes, opens tomorrow, 3/5 stars).

Screenwriter Abi Morgan (The Iron Lady, 2011; Shame, 2011) invents the character of laundress Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a fictional participant in real events of the early 20th century that lead to British women getting the vote.

The passive Watts is radicalised after years of being treated as a slave and sexual object by her boss, and also by seeing the work of women willing to speak out, among them historical figures such as Emmeline Pankhurst (Meryl Streep) and Emily Davison (Natalie Press). The consequences of her work in the women's movement are severe; she is punished both at home by her husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and by the police in the person of Inspector Steed (Brendan Gleeson).

This is a story that needs to be told, but director Sarah Gavron (the critically acclaimed immigrant drama Brick Lane, 2007) fails to get a clear line through the sprawling story or a handle on its large number of characters. Watts embarks on a hero's journey of a sort, but one that sets up expectations that the story fails to satisfy. While the idea of state repression, personified in the cop Steed, might be historically accurate, it is a loose thread, one of several.

The strength of Mulligan's performance saves this work, giving it a backbone without which it would have collapsed.