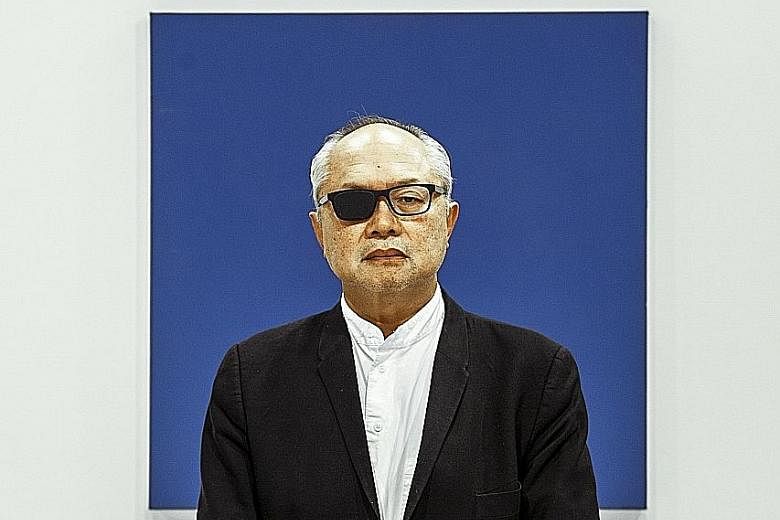

NEW YORK • Twenty years ago, conceptual artist Mel Chin cold- called the offices of Melrose Place, United States producer Aaron Spelling's wildly popular prime- time soap opera, with a proposition.

What if a task force of artists supplied free artworks and props for the show's apartment-complex set, with coded cultural messages on pressing topics such as reproductive rights, American foreign policy, alcoholism and sexual politics?

Deborah Siegel, the show's set decorator, had an instant reaction. "I thought it sounded really interesting," she said in a recent interview. "So I met him."

In late 1995, Chin and a team of 100 mostly unknown artists, called the Gala Committee, began a two- year experiment, placing objects on Melrose Place. They took their cues from scripts and worked with the writers to modify plot lines and develop characters.

From today to Nov 20, at the Red Bull Studios New York, 100 objects from the set go on display in the exhibition Total Proof: The Gala Committee 1995-1997.

The show will be, appropriately enough, a rerun. Viewers of Melrose Place saw a version of it in April 1997, in a television episode featuring an actual exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Uncommon Sense, which included many of the works produced for the set.

In it, actress Heather Locklear, as hard-charging advertising executive Amanda Woodward, has just taken on the museum as a client and brings her love interest, Kyle McBride (Rob Estes), to the opening for an evening of art talk.

Much of it takes place in front of a Ross Bleckner-like painting that alludes to the US bombing of Baghdad. That work was ordered by Carol Mendelsohn, the show's head writer.

This fictional opening, filmed two weeks before the museum's opening, was one of the great meta moments in television history.

The Melrose Place idea began when Chin was shuttling back and forth between the University of Georgia, where he held a temporary professorship, and the California Institute of the Arts, where he was conducting a workshop.

"We discussed pop culture and Hollywood," said Ms Valerie Tevere, one of his Cal Arts students. "How might artists work with TV."

Chin had never heard of Melrose Place. "I was not watching much television at the time," he said in a recent interview.

But he recalled that while on a flight from Atlanta to Los Angeles, he looked out the window and thought "Los Angeles is in the air".

The city existed in the trillions of electronic impulses its residents sent through the atmosphere and around the world, transmitting social content and cultural symbols.

"Our world is transformed by covert information, political messages," he said. "How would that work if it was art?"

Back home, he watched as his wife flipped the remote control and stopped on an arresting image. "I saw this large blonde face filling the screen, with blue eyes," he said. It was Locklear. "When she moved, there was a painting behind her, and I said, 'That's the gallery.'"

He began assembling his troops, including students, professional artists, a media scholar (Ms Constance Penley of the University of California, Santa Barbara) and an actual fan of the show, Mr Mark Flood, an old friend of his from his native Houston.

Frank South, an executive producer for the show, and Mendelsohn decided not to mention the project to Spelling or the network brass. Eventually, word leaked out when The New Yorker ran an article, Agitprop, timed to the opening of Uncommon Sense. South said: "I was busted."

Spelling, tickled at the idea of seeing Melrose Place in the museum world, took the news well. "Just don't do anything to hurt the show," he told his charges.

In early 1996, with the series in its fourth season, the artwork began to arrive. As a safe-sex message, committee members designed Safety Sheets for womanising Dr Peter Burns (Jack Wagner) - bedsheets in an all-over pattern of cylindrical shapes that, on close inspection, turned out to be unrolled condoms.

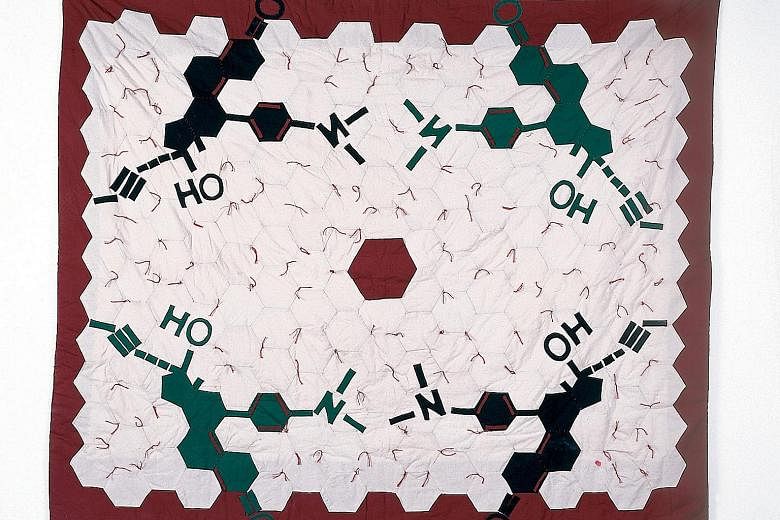

When Alison Parker (Courtney Thorne-Smith) became pregnant, the Gala Committee made her a quilt appliqued with the chemical symbol for the morning-after pill RU-486.

Ms Penley said: "In network TV, no matter how strong you are, you cannot have an abortion. You either have the baby or you fall down the stairs. We wanted to put reproductive choice back on network TV."

The Gala Committee called it a day after the museum episode in 1997, but the series continued until May 1999. "We were exhausted, basically," Chin said. "It was very stressful, producing on deadline."

NYTIMES