On her first day at work as a choreographer at the then Singapore Broadcasting Corporation in 1984, all eyes were on dance pioneer Angela Liong.

"I was in my hotpants. Nowadays, girls wear hotpants, but you should have seen my hotpants, okay! I wore no bra, a loose top, carried a huge dance bag and marched right into SBC," she recalls, chuckling at the memory.

"People went 'ahh?' But I was a dancer, what do you think?"

Three decades on, her rebellious streak is still as strong as ever. The 63-year-old is now the full-time artistic director of The Arts Fission Company, one of the oldest and most unorthodox contemporary dance groups in Singapore. Alongside regular performances, the group also takes part in medical research, runs visual arts classes for children and conducts creative movement-based therapy for the elderly.

Juggling all these programmes requires an abundance of energy, which fortunately, Liong seems to have plenty of.

During the three-hour interview with her at Arts Fission's office in Cairnhill Arts Centre, she barely pauses for breath. She makes her points swiftly, her hands a flurry of gestures to elaborate on or emphasise a point.

It is this tireless energy that has stacked her shelf full of accolades. In 2009, she received the Cultural Medallion award in dance. In the nascent years of the dance scene here, she founded the first full-time dance diploma programme at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, and also the first dance degree programme in Singapore, in affiliation with the Queensland Technological University.

To her, though, recognition is not as important as tangible support. When asked about her Cultural Medallion, she frowns slightly.

"I don't want to sound crass," she says carefully. "But it's like, so what? I still have to line up and take a number in terms of getting support and resources. It's not an exclusive club membership card which opens doors for me."

This unconventional attitude has been firmly rooted in Liong since young and is most likely the result of a childhood which spanned continents and cultures.

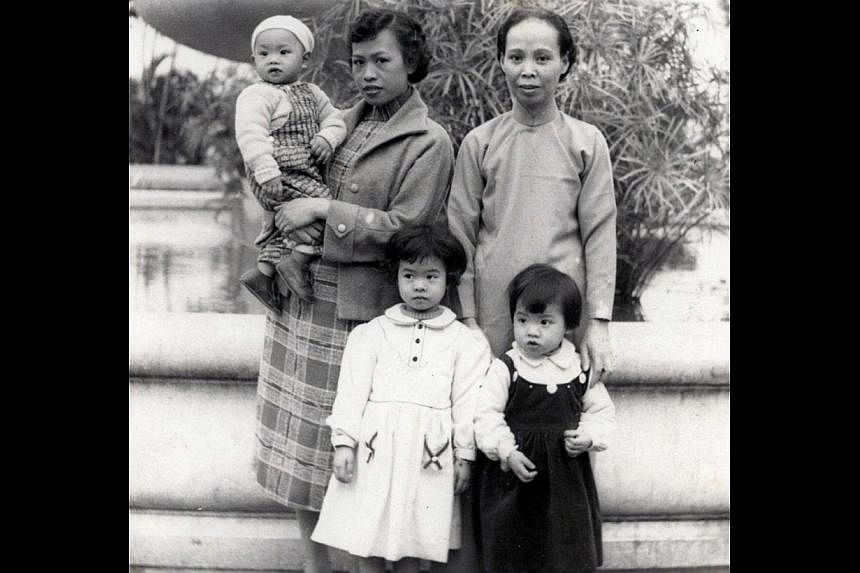

She was born in Guangdong, China, in 1951, the oldest of four siblings. Her mother was a housewife, her father an instructor at a military academy and later chief manager of a steel factory.

Growing up, she was not a typical lass. "I was never a little princess or a Hello Kitty girl. I hated that. I liked to do things in a direct way," she says. "I remember my granduncle gave me a nickname, Captain, because I was always the one who was instigating bad and naughty things, and getting the other kids to listen to me."

When she was five, her family left Communist China for British-ruled Hong Kong. When she was 16, they moved again to Chicago in the United States, where her father was to help out with the family business.

Liong comes from a long line of migrant Chinese. Her great-grandfather built part of the American railway in California, while her grandfather owned a series of Chinese restaurants and other businesses in Chicago and the state of Iowa.

Even today, her parents and siblings are settled in the New England area, near Boston. She tries to visit them at least once a year.

When Liong moved to the US, school life was tough. Alone in an unfamiliar environment, surrounded by blond- haired, blue-eyed jocks and homecoming queens, she went from being a mischievous, outspoken child to a withdrawn teenager.

"I was very out of it. I was very quiet because it was a strange culture. It was almost like I took a vow of silence for three years," she says pensively.

It was then that she began to seek refuge in the arts.

"I found my sanctuary in the choir and in the art club. I was the darling of the art teacher, she loved me in high school and music became a very important part of my life," she says.

It became such a major focus that the lyric soprano attended the music conservatory at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, after high school, and joined a summer opera company.

However, her burgeoning opera career was brutally cut short just a year into her full-time music studies. After she failed a singing audition, the head of the school's voice department told her: "You are an Asian and there are very few operatic performance roles for an Asian."

"I was devastated and totally crushed," she says.

After that blow, she left the conservatory to seek another path. She ended up at the University of Iowa, a two- hour drive away from home.

It was at university that she had her first serious encounter with dance. Although she majored in East Asian language and literature, she took a module in contemporary dance, which covered both technique and theory.

More importantly, her university years were also when she first dipped her feet in the professional arts world. As she took a module in translation, she helped out at the prestigious International Writers Workshop, founded by American writer Paul Engle and his wife Nieh Hualing.

"I got to see behind the scenes of arts and culture. I saw what their interpersonal relationships were like, how you charm and interact with rich potential sponsors. That was lesson 101 for me," says Liong.

She refers to that period of time as her "wild days". She adds: "Hey, when you're around a whole bunch of international writers... I had a Romanian writer feeding me grapes. That was the life. It was wild, it was drinking, smoking and everything else."

It was only towards the end of her university life, "when I was just starting to calm down", that she met her husband, Dr Liong Shie-Yui. The Indonesian-born Chinese was studying engineering. Now, he is acting director of the Tropical Marine Science Institute at the National University of Singapore.

Liong says that after a series of tumultuous relationships, meeting him was like a breath of fresh air.

"He's a very level-headed person, very generous. I think that's what really impressed me," she says, breaking into a smile. "I think after a lot of complex and dark relationships, that came like a ray of sunshine."

Dr Liong, who is in his mid-60s, was enamoured with her fierce singlemindedness.

"Her perceptive nature to see through things, her unwavering focus on and passion for projects and issues she started and the determination to bring them to fruition; her resilience and her curiosity about everything and her warm companionship are the qualities which attracted me most," he says.

The couple met in 1976 and, after a whirlwind courtship, registered their marriage a year later.

They moved around the US for work, staying in Washington DC for a year and Mississippi for five. There, Dr Liong worked as assistant professor at the University of Mississippi, while Liong completed her master's degree in English and dance at the same institution.

But there was a dark cloud on the horizon of the Liongs' newlywed bliss, as Dr Liong's father, who was living in Indonesia, developed Parkinson's disease and glaucoma. Wanting to be closer to him, the pair moved to Singapore in 1984, with the intention of "just passing though".

Little did they know that they would end up staying here for the next three decades.

"Sometimes, looking back, especially when work has been so intense, you don't realise that all this time has gone by," she muses.

Her first job in Singapore was to choreograph for the now-defunct Singapore Broadcasting Corporation. However, working in local television meant having an intimate knowledge of local culture, which she did not yet possess. Her first work for the station was an outdoor, food-themed concert.

"They told me, you have to do a dance about roti prata. I said, 'What's roti prata?'," she recalls with a laugh.

Despite her initial cluelessness, she quickly laid down roots in her adopted country and was granted permanent residency the following year.

She stayed with the broadcasting station for six years, until she began to feel the familiar tension between doing commercial and artistic work.

In 1989, she was invited to the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts to create and spearhead its dance diploma programme. However, a lack of administrative support and student registration meant that running the course was an arduous task.

"In the early days, if I can be frank, it was a mess," she says. "In our first batch, we had only nine students. Every management meeting, they would say, this is not sustainable, let's close it down."

The curriculum which she designed featured Western ballet, contemporary and jazz, as well as traditional Indian bharatanatyam, Malay folk dance and Chinese dance.

While enrolment in the dance diploma programme never surpassed 20 students a year, the course did produce several notable dance practitioners.

Ricky Sim, artistic director of contemporary dance company Raw Moves, first trained under Liong as a part-time student in 1988.

"She made me question everything and from this inquisition, I've learnt to love the subject of ontology, of questioning what is being," says the 44-year-old. "She taught me to stretch my mind in different directions and that's important in the making of who I am today."

She left the academy in 1996 to join Lasalle College of the Arts as head of contemporary dance and head of the junior school of creative arts. A year later, she was promoted to dean of the school of the performing arts.

Despite the plum job, she left Lasalle just three years after she joined, in 1999. Again, she faced disagreements with the school's management.

"The president told me, 'Your dance department is still small, you should affiliate yourself with some of the local ballet companies'," says Liong. "But I thought no, we need to strike out on our own. I'm a creative artist, I'm not your usual administrator."

After she left the education industry, she threw herself into running Arts Fission full-time.

"The time was ripe and the scene had just started. You need to put 200 per cent into anything, if not, it won't happen."

It was also this sense of untapped potential that kept her in Singapore: "It was the unformed stage of making art that made me stay. It's opportunity, possibility, potential. These elements made me slow my step."

However, earning her place as one of the forerunners of the industry has taken a toll on her personal and social lives. Liong does not have any children, and when asked why, she fumbles for the first and only time in the interview: "I think after a while, I umm... I just think you can't... things probably, we were very adamant about, you know, but again, it didn't work out."

"Work was too consuming," she finally manages. "At such a pioneer stage of art development, the work was too time- consuming, it consumes your personal life, it consumes everything you have."

Her company, with five full-time dancers, has staked out a very unusual spot in the dance landscape here. Arts Fission does not just create dance productions, it also explores, questions, researches and works with the less privileged sectors of society.

The company conducts weekly creative movement-based sessions at eldercare homes and is developing training manuals and instructional DVDs to facilitate the teaching of the programme at other centres. It has also worked with oft-overlooked groups, such as at-risk youth and samsui women for productions.

Its works are also not just about the visual impact of dance, but using movement as a tool to explore, understand and communicate.

A lot of her work is rooted in her surroundings: The 1998 haze triggered a series of pieces on environmental change, and Follies For E Birds, at the National Museum and part of the annual Singapore Night Festival, is about animal and human migration.

In short, the company feels like an extension of her, a cerebral limb that explores the world around her. However, such a deeply personal involvement in the company also makes finding a successor difficult. Liong, almost predictably by now, is nonplussed.

"If I can't find anyone, we will just close the company. Everybody's had fun, everybody can go home now. This is not a dynasty. This is not a corporation," she shrugs.

That attitude, a strange blend of frankness and flexibility, sums her up. Speaking to her, you get the sense that she flows around and through obstacles like water, and that there are no wrong turns in life, only unexpected ones.

"Regrets?" she laughs when asked if she has any. "No, I have no regrets and I think that feeling regret or opportunities missed is meaningless. Life is an ongoing journey."