FICTION

THE GLASS HOTEL

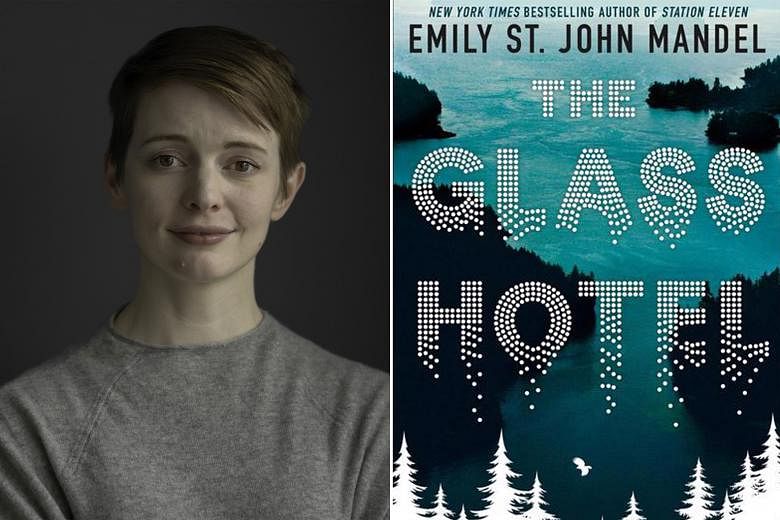

By Emily St John Mandel

Picador/ Hardcover/ 320 pages/ $31.11/Pre-order at bit.ly/TGH_EM/4 stars

"Why don't you swallow broken glass," someone scrawls in acid marker on the wall of the Hotel Caiette, a glass-and-cedar palace on a remote British Columbia island where people go to experience the wilderness - or rather, pay a lot to look at it through glass.

It is an arresting image, one of many that glint throughout Canadian writer Emily St John Mandel's latest novel, a marvel of surfaces that is oddly depthless.

Mandel's last novel was the luminous Station Eleven (2014), in which a deadly flu wipes out most of the world's population.

It is, in this reviewer's opinion, the best post-apocalyptic novel of the last decade and is now, with the coronavirus pandemic, frighteningly germane.

Those looking for a satisfying sequel will not find it in The Glass Hotel, even though these two novels seem to take place in the same universe and share some characters.

The Glass Hotel begins with a woman called Vincent falling from the deck of a ship at sea and then shifts and flickers through a web of storylines with glancing connections.

There is the Hotel Caiette, where a younger Vincent works as a night bartender.

There is Paul, Vincent's dissolute half-brother, an aspiring musician and recovering drug addict, and Vincent's vanished mother, who named her after the poet Edna St Vincent Millay - a name that matches the author's in rhythm.

There is the unimaginably wealthy Jonathan Alkaitis, who hires Vincent as a "trophy wife" for a time and masterminds a massive Ponzi scheme that, in collapsing, destroys countless lives.

At its core, The Glass Hotel is a ghost story - people are literally haunted by the consequences of their actions - and a meditation on the fragmented, transitory nature of life, as themes and characters check in and out of the narrative.

Some segments are stronger than others. Especially captivating is Vincent's time in what she calls "the kingdom of money", as well as The Office Chorus, a virtuoso sequence in which Alkaitis' employees try desperately to cover up the unravelling scam, swinging between second-person plural and third-person singular as loyalties war with self-preservation and guilt.

Paul's section is the weakest and there is not as much of the Hotel Caiette as one would like to see.

St John Mandel remains an alluring writer and there is much to admire in the hallways of The Glass Hotel - but one is not inclined to extend one's stay.

If you like this, read: Hotel World by Ali Smith (Penguin Books, 2002, $18.66, available at bit.ly/Hotel_World). There are five people in this book: four are living, three are strangers, two are sisters, one is dead. A hotel chambermaid falls to her death in a dumbwaiter, while a receptionist offers a homeless woman a room for the night.

- This article includes affiliate links. When you buy through affiliate links in the article, we may earn a small commission.