REVIEW / THEATRE

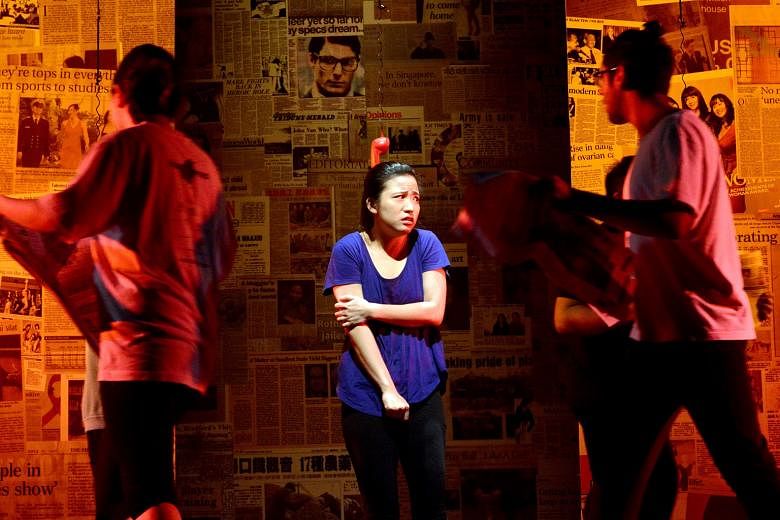

EVERY SINGAPOREAN DAUGHTER By Unsaid

KC Arts Centre

Last Friday

The production Every Singaporean Daughter by arts collective Unsaid, which crowdsourced stories from Singaporean women for its plot, handled thorny topics such as gender, race relations and class divide with maturity and nuance.

Director Praveena Cartelli and playwright Marie Ee strung together multiple plotlines of characters, each struggling to reconcile her identity and desires with the crushing weight of societal and familial expectations.

The protagonist Chloe Lim (Amber Lin) picks wushu as her school activity of choice and her overprotective mother (a brilliant, indefatigable Deborah Hoon) disapproves. Chloe, however, finds her coach (Lyon Sim) making inappropriate advances towards her.

Meanwhile, her brother Daniel (Darren Guo) and his Malay- Muslim girlfriend Iman (Rusydina Afiqah Razali) also fight an uphill battle in finding family acceptance for their relationship.

One recurring theme was vulnerability and the tendency to associate women with that quality.

Chloe justified her choice of wushu by telling her family: "If I stopped fighting, I would stop living."

Her aunt Peggy, who influenced her to switch from "ballerina to batman", also practised wushu to overcome childhood insecurity. Peggy's sexual ambiguity also leads Chloe's father to dub her a lesbian, in a clear display of how society tries to box people up.

Security can be found only in a man and starting a family, as both Chloe and Iman's mothers repeatedly exort them to do. But the irony weighs heavy, as Chloe's life is undone by that in the play's brutal ending.

The tension ratchets up as she persists with wushu, but is repeatedly roughed up by her coach, who even muzzles her screams at one point.

In a stark parallel, Iman, a history graduate with political aspirations, is silenced in an argument with her chauvinistic, overbearing brother Hafiz when he threatens to stop paying for her tertiary studies.

Such scenes stick in the mind as grim reminders of how even the most dogged and vocal women are eventually felled by the power structures in society.

But the play also took pains to portray its male characters with nuance. One effective scene focused on Daniel, who runs through the pressures of growing up as a man: One must ace his physical tests, go to officer cadet school and secure a place in law school to be the perfect Singaporean son.

A revealing scene in which the Malay siblings recalled how their family unravelled in the wake of their father's death also softened Hafiz's image. Barely out of school, he had to become the head of the household.

Ee's writing sometimes veered into melodrama, especially during the family dinner scenes. But there were glimmers of potential. One instance was how Iman and Daniel broached their differences on issues such as abortion and his conversion to Islam with candour and sensitivity.

Cartelli's decision to physically project Chloe's conscience using an actor (Wendi Wee Hian) repre- sented how the character's inner desires were always at odds with her performed self and made for an interesting duality in movement. At other times, an actor's monologue was accompanied by members of the cast, which felt distracting.

But such minor hiccups did not detract from a play that portrayed the silent anguish of women in our modern yet conservative Asian society in a thoughtful and thought- provoking manner.