1967: The Death Of The Author, an incendiary little essay by French theorist Roland Barthes that changes the face of literary criticism forever, is published. "The birth of the reader," he writes, "must be at the cost of the death of the Author."

1980: The death of its author. Barthes, crossing the road after lunch, is hit by a laundry van and dies a month later in hospital. A stupid accident that just happens to kill one of the leading critical minds of the time - or is there something more?

What if Barthes, in his last moments, was carrying an all- important secret document? What if it unlocked an unprecedented power of language, a weapon of mass linguistic destruction that must at all costs be kept out of the wrong hands?

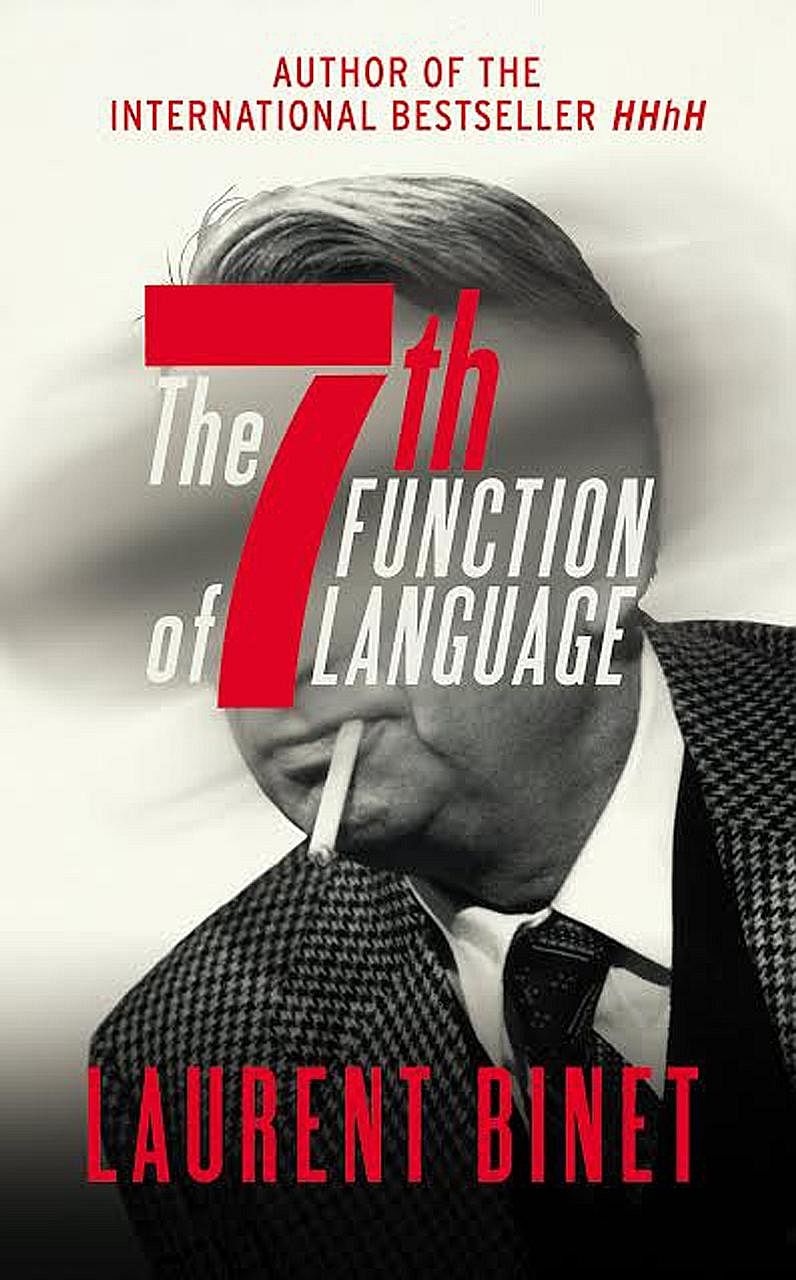

So French novelist Laurent Binet would like to think. In The 7th Function Of Language, this motoring mishap morphs into a manic murder mystery, featuring continental philosophy, Bulgarian spies with poison-tipped umbrellas (a historical fact, by the way) and what is, theoretically speaking, an underground fight club.

Binet was awarded the Prix Goncourt, widely considered France's most prestigious literary award, for a first novel for his debut HHhH (2010), about the assassination of Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich.

He wrote The 7th Function, his second novel, in French in 2015, with an English translation that came out earlier this month.

Barthes, says the 44-year-old over the telephone from Paris, has had an enormous influence on his thinking since he encountered him as a literature student at the University of Paris.

Barthes was a semiotician - semiotics being the study of signs in linguistics - who produced seminal texts such as Mythologies (1957), which analyses modern cultural phenomena such as wrestling, soap advertisements and the face of film star Greta Garbo.

"He gave me a guide not just to read texts, but also to read the world," says Binet, who is single. "He made me smarter, or at least less stupid."

So he owes Barthes a debt, although the semiotician is not his favourite philosopher - this honour is reserved for Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction theory.

"Derrida's thoughts are very sexy," he says. "I like the way he questions the root of everything and I try to do the same with my book. I want my novel to deconstruct itself."

Barthes, Derrida and a bevy of other famous critical thinkers parade through the novel as characters. Michel Foucault lounges naked in a bathhouse; Umberto Eco is attacked by hippies in a Bologna bar; Deleuze and Guattari have their own brand of drugs, hawked at university parties.

But Binet hopes everyone, not just erudite fans of critical theory, will enjoy the novel. The reader's guides into the complex world of continental philosophy are Bayard, a policeman investigating Barthes' death, and Simon Herzog, an academic press-ganged into helping him. It helps that there are car chases and explosions galore.

One of the novel's highlights is the Logos Club, a secret society that melds sophistry with the heady violence of Chuck Palahniuk's cult novel Fight Club.

The first rule of Logos Club may be that you do not talk about Logos Club, but once inside it, you had better know what to talk about. Its members duel one another verbally to rise through the ranks, but losing an argument will cost one a finger.

Who would Binet fight, if he found himself defending his digits in Logos Club? "Augustine," he decides, naming the second-century Christian monk behind works such as Confessions and The City Of God. "One of the great thinkers of the church. These would be very hard to defeat, but they are such strong believers, I'd like to fight them. I could not fight somebody I despised."

Above all, Binet explores the power of language, which in the novel becomes something worth killing for. The characters get caught up in the French presidential election between the centrist Valery Giscard and the leftist Francois Mitterand. Both want to get their hands on the seventh function to defeat the other at the polls.

It is sheer coincidence, says Binet, that the book's new translation emerged at the same time as the recent election that saw independent Emmanuel Macron beat far-right Marine Le Pen to the French presidency.

"There is no power without the art of discourse," says Binet, who is working on a third novel set in the 16th century. He is no stranger to politics, having written a book about being embedded in the campaign team of former French president Francois Hollande.

The seventh function, he adds, is but a tool and, like all tools, can be used for good or bad. "The one who gains control of the discourse gains domination and power.

"But to be the king of language these days, you have to be good with short sentences because now, it is Twitter time," he quips, referring to the social media addiction of United States President Donald Trump. "More than ever, you need a punchline."

•The 7th Function Of Language by Laurent Binet ($29.95) is available at Books Kinokuniya.