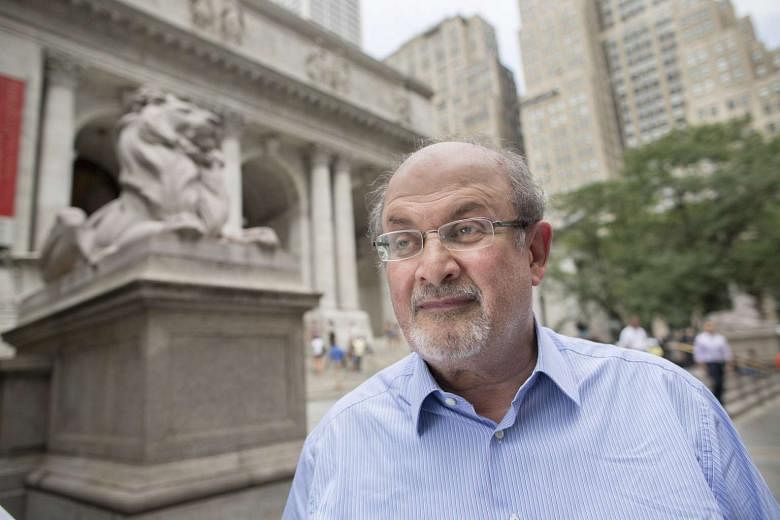

NEW YORK • Salman Rushdie was a teenager when he first learnt that his last name was invented rather than inherited.

"My grandfather wasn't called Rushdie," he said. "My father just made it up. He made a really good choice. It came from his interest in the philosophy of Ibn Rushd."

Later, Rushdie came to share his father's obsession with the work of Ibn Rushd (pronounced Roosht), a 12th-century philosopher known in the West as Averroes.

Now, he has made him a central character in his new novel, Two Years Eight Months And Twenty- Eight Nights. The novel opens in 12th-century Spain, where the philosopher has unwittingly fallen in love with a beautiful woman named Dunia, who is actually a jinnia (or genie) in disguise.

The story jumps to New York City in the near future, as Ibn Rushd and Dunia's distant descendants discover they have superpowers or turn tree branches into gold. (Some of their superpowers are more like minor inconveniences: A gardener named Geronimo hovers a few inches off the ground, but is otherwise fairly average).

In the final chapters, the supernatural beings take part in an epic war being fought by powerful genies over the future of humanity, leading to an action-packed climax that reads in places as if Kafka had written a blockbuster superhero movie.

During a recent interview at his publisher's office in Manhattan, Rushdie spoke about his love of science fiction, his failed television series and his falling out with novelist Peter Carey.

This novel shares some of the themes you have explored in the past, like the conflict between religious belief and reason, but, stylistically, it feels looser, mashes up mediaeval philosophy and Islamic mythology with an almost Marvel Comics-like sci-fi universe. What inspired you to create these superhero characters and a War Of The Worlds- style fantasy plot?

Science fiction is where I started out, really. When I was a kid, I was a complete addict of science fiction. It was one of my earliest interests as a writer and I've just taken a long time to circle back around to it. It was also a reaction against writing my memoir. I'd spend two or three years trying really hard to tell the truth, and, by the end, I was sick of the truth - enough truth, let's make some (expletive) up.

One of the narrative threads in the novel has to do with the centuries-old philosophical debate over reason versus faith, which you bring to life by having powerful jinn wreak havoc on the world, upending the laws of physics. Why was fantasy a good vehicle to illustrate these abstract ideas?

It connected in my mind to this idea I had about living in a world where the rules are breaking down, where the world is changing so fast in all directions that a lot of people have a sense of bewilderment. You don't actually know what the rules are anymore and you have a sense that maybe there are other people much younger who do know what the rules are and are thereby making billions by inventing, what, Snapchat? What the hell is that? That, apparently, is worth billions. Novels are worth, if you're lucky, a six-figure sum.

Do you use Snapchat?

No. I know that it exists.

A few years ago, you were working on a sci-fi series for Showtime. What happened to that?

That died, like all these things do. The thing that I had been developing for Showtime was also a kind of a parallel - world story, in which it was our Earth and another variation of it, and they somehow come into contact with each other. Anyway, that didn't happen, but I had been thinking a lot about these parallel world ideas, and how do you make that happen, and what are the complications of it. So I now see that as having been interesting preparatory work for the way this book turned out.

Will you maybe revive the sci-fi plot for another network?

I've got the rights back because I've got a good lawyer. But I'm not sure the creative juice is there anymore. I've already used that idea.

I hear you watch Game Of Thrones.

I like the girl with the dragons, and I like the short guy, and I want them to win.

You were very vocal in supporting the PEN American Center's decision to honour French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo this year, something that some other writers including Carey and Francine Prose opposed because they said the magazine perpetuated bigoted ideas. Were you surprised to be on the other side of an ideological divide from some of your peers?

I could not believe it. Still can't believe it. So many writers who are old friends. It was really shocking. Now, of course, the lasting damage is in some of those friendships. I haven't seen any of them nor have any of them been in touch with me.

I felt a sense of injustice that these people were executed for drawing pictures. If we're a free-speech organisation, how can we not be on their side? For Carey to say to The New York Times that he didn't see it as a free-speech issue, I thought, "What?"

He's a friend of yours, right?

Well, was. It's bewildering and saddening.

The United States is on the brink of possibly ending sanctions against Iran and opening up diplomatic relations. As someone who was given a death sentence by the country's religious leaders, how do you feel about this development?

Truthfully, I really do not know what I think. I am quite conflicted about it. On the one hand, the last decade or so shows us that war hasn't worked, so maybe try peace. The other argument is, we're talking about Iran. These are, how shall I put it, unreliable people. I'm on that strange ground where I don't quite know what I think.

Which is all right - I'm a novelist. Fortunately I don't have to rule the world.

You have taken to Twitter to engage with your fans and occasionally trade barbs with critics. What appeals to you about it?

I have very up and down feelings about Twitter. There are long periods where I can't be bothered. I like it for bringing me information. And, of course, it's useful to be able to tell people you just published a book when there's a million people following you. Then you look at Neil Gaiman and then you begin to feel ashamed of just a million people. And then you get to the real enormous intellectuals of Twitter, you get to Justin Bieber and Kim Kardashian, and then you just feel like a worm. Just a million. There are times when I kind of agree with Jonathan Franzen's view that you should just stay away from the stuff.

You've teamed up with other artists on various projects (including a sculpture with Anish Kapoor and a ballad with U2). What appeals to you about working with artists in other mediums?

I don't look for these collaborations. There was this very funny moment, just after U2 and I made that song. When it got out that U2 and I had collaborated, there was, like, five minutes when every British pop group thought, oh, Salman Rushdie, we could write a song with him.

So, can we look forward to a One Direction album with Salman Rushdie?

I'm open for offers. Talk to my agent, as they say.

NEW YORK TIMES