FICTION

AT DUSK

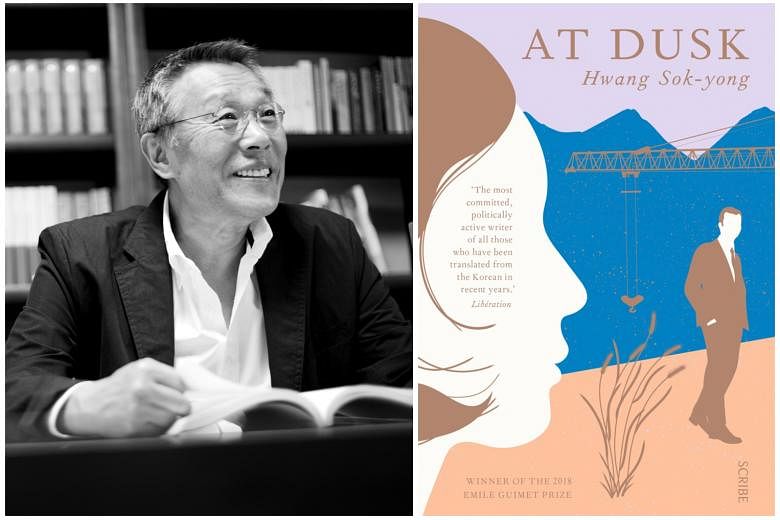

By Hwang Sok-yong, translated by Sora Kim-Russell Scribe/Paperback/188 pages/

$22.95/Books Kinokuniya/

4 stars

With his quiet wisdom, incisive eye for detail and contemplative take on modernity, Hwang Sok-yong, 75, has earned a reputation for being one of South Korea's most eminent and critically acclaimed writers.

The melancholic artistry of his bare prose shines through in At Dusk, with the juxtaposition of the nostalgia of a bygone era and a soulless modernity.

He takes a hard look at South Korea's tribulations as a third-world economy under the dictatorship of former leader Park Chung-hee, who ruled from 1963 to 1979, and the present-day struggles of its youth, in a country where the youth unemployment rate stands at 10.5 per cent.

Besides poverty, he also takes on pertinent themes such as the depopulation of rural towns and these towns' modern upgrades that cause them to lose their former character.

Hwang fittingly taps as his protagonist Park Min-woo, a successful architect who had been born into poverty, but used his street smarts, ambition and talent to climb the social and meritocratic ladder to head a large architectural firm.

But his past catches up with him. A sudden, mysterious message from childhood lover Cha Soo-na one day prompts him to return to his home town where he takes a hard look at his role in steamrolling the past.

"I couldn't wrap my brain around how civilised it had become - my home town, which now had more people who'd left than people who'd stayed. The boxy two-and three-storey cement buildings that occupied downtown from the shopping area all the way to the residential area looked bleaker than ever," Park narrates.

"It was as if me, my long-departed parents, and even my home town itself had never really existed."

Another main character is the young and struggling theatre playwright Jung Woo-hee, who has to juggle rehearsals for an upcoming play and works the graveyard shift at a convenience store just to be able to afford a roof above her head.

"As I lie in bed, looking up at that stain spreading across the wall, I suddenly feel breathless, like I am suffocating, and fight the urge to scream hysterically," she says.

She adds of her peers who are struggling like her: "They reminded me of the tiny mammals who cower among the beasts of prey deep in the jungle and must survive on their wits alone."

In At Dusk, Hwang taps a common narrative trope of having seemingly disparate and unconnected story arcs that converge in the closing chapters - albeit to somewhat unconvincing effect though perhaps typical of a Korean melodrama.

The septuagenarian himself has a dramatic past, having spent years in jail as a political prisoner, including a seven-year sentence in 1993 for an unauthorised trip to North Korea to promote cultural exchanges.

He has earned high praise from fellow East Asian writers, including Japan's Nobel Prize for literature laureate Kenzaburo Oe, 84, who has said Hwang is "undoubtedly the most powerful voice in Asia today".

And this voice is resounding in At Dusk, with its bittersweet meditation of regret.

If you like this, read: Please Look After Mom by Shin Kyung-sook (Orion Publishing, 2012, $18.95, Books Kinokuniya). In this haunting look at what "family" means in Korean culture, family members search for their mother when she goes missing at a subway station, but soon realise they do not really know who she is.