SINGAPORE - At 4am, encircled by smoke from the various wildfires blazing through California, renowned travel writer Pico Iyer turned on Zoom and beamed at more than 950 viewers half a world away in Singapore.

Iyer, 63, seemed chipper given the early hour and the environment, especially for someone who, in 1990, watched his house burn in one of the worst man-made fires in Californian history.

The house was surrounded by 25m-high flames, he recalled. From the road, he watched them systematically burn through the living room and reduce everything in his bedroom to ash, wiping out eight years' worth of writing for his next three books.

If somebody had asked him then where his home was, he would have had nothing physical to point to.

"Home is not the place where you live," he said. "Home is what lives inside you. And I think these days, even somebody who's got a very fixed sense of home has to have a global perspective."

Iyer was speaking on Tuesday night (Sept 8) about localism and globalism as part of the Lien Fung's Colloquium series, organised by Singapore Management University.

"It's impossible to have globalism without the local component," he said. "And it's dangerous to have localism without global vision."

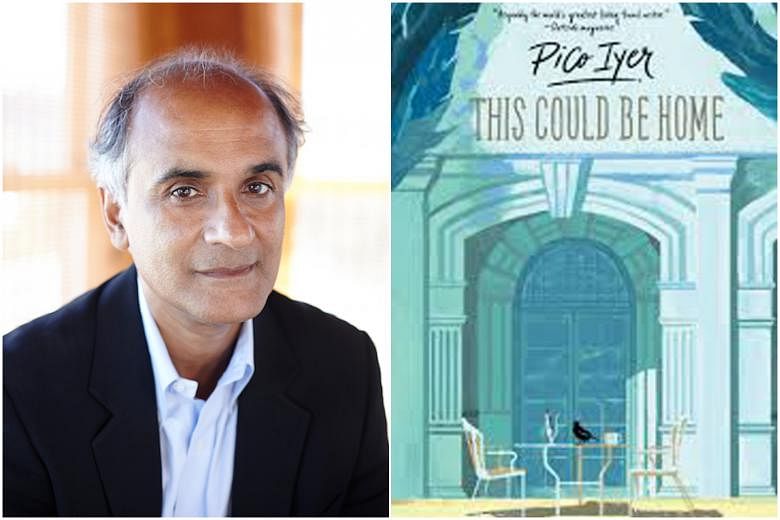

Iyer, who is among the best-known travel writers living today, has written more than a dozen books, including last year's Autumn Light, A Beginner's Guide To Japan and This Could Be Home, about Singapore's Raffles Hotel.

In the webinar, he spoke of his own background as an "international co-production" who transcends borders. Born to Indian parents in Britain, he divides his time between the United States and Japan, where he lives with his wife Hiroko Takeuchi and two children.

He sees not belonging to any one tribe - and its attendant loyalties and enmities - as a "great liberation".

"Somebody like me can in some ways be defined not by my passport, but by my passions," he said. "Home doesn't have to be the place that you come from. Home can be the place where you go. In all kinds of ways, I think this frees us from some of the problems of yesteryear.

"In my case, home became almost a collage, a stained-glass hall to which I was constantly adding new elements and trying to keep them in harmony. Home became a sentence I would never complete."

He thinks that nationalism seems to be on the rise because it is in fact "on the run", as globalism increases inexorably.

"Every time one of you falls in love with somebody from another tradition or another culture, the children who might arise out of your union will fling another black-and-white division out of the window."

He has seen such changes occur in his lifetime. "I remember how, when I was very small, 98 per cent of Americans disapproved of mixed-race marriages. The number in 2014 was 3 per cent. That's an extraordinary change in one lifetime."

2020 has served to illustrate everything good and bad about globalism, he said. "The story of this curious year is how much a local sneeze has global consequences, that what began with one individual in a little market in Wuhan can to some extent paralyse the entire world.

"On the one hand, the virus began locally and spread across the world very quickly. On the other, a vaccine will arise at one lab and, we hope, will spread across the world very quickly.

"On the one hand, nearly everybody in every country has had to stay at home. On the other, in ways I literally couldn't have imagined 20 years ago, I get to talk to you and see you onscreen while being 8,000 miles away.

"That was not possible in the year 2000 or 2005. And it means that even as we're all sitting apart, we're in some ways standing together."