Violinist Min-Jin Kym made international headlines seven years ago when her rare Stradivarius violin was stolen at a London train station, and again three years later when it was miraculously recovered by the police.

But this happy ending - the ecstatic musician reunited with her £1.2-million (S$2.1-million) instrument - would turn out hollow.

Opening up years later, the 38-year-old reveals that due to insurance complications, her beloved violin never truly returned to her.

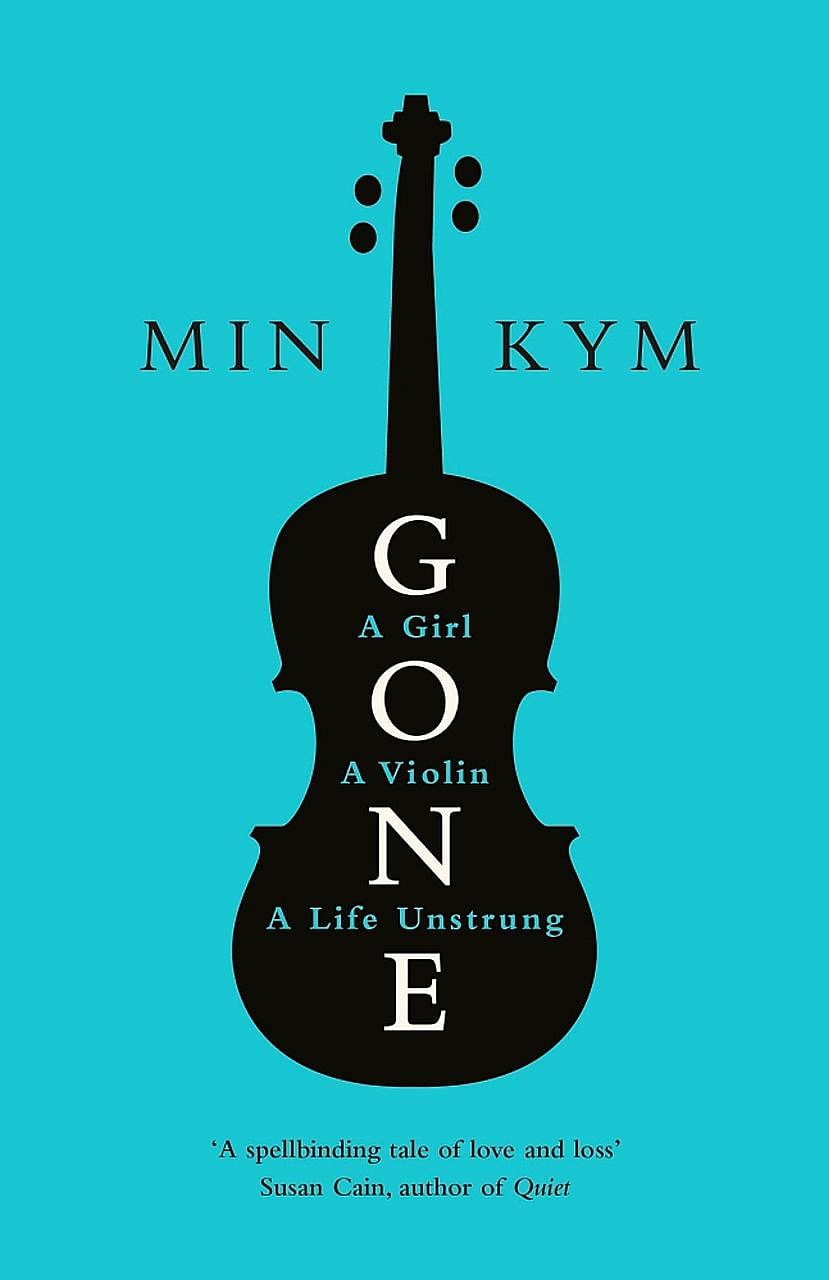

Her new memoir, Gone, is an insight into the life of a child prodigy and an attempt to convey to the layman the incredible bond a musician forms with his or her instrument, and how the theft of her Stradivarius unstrung her life.

"It's not something I'd expect somebody who's not a musician to understand," says Kym over the telephone from London, where she lives. "Why should they?"

Kym, a South Korea-born prodigy who grew up in Britain, became, at the age of seven, the youngest pupil to join the illustrious Purcell School of music. She won her first international music competition at the age of 11.

She met her violin when she was 21 and it was a little more than 300 years old. It had been crafted in 1696 by Italian luthier Antonio Stradivari, considered the greatest violin-maker to have lived.

Drawing her bow across its strings for the first time, she writes, was her Cinderella moment, the glass slipper sliding perfectly onto her foot.

"All my life had been a rehearsal... everything leading up to now, when I would meet my violin and we would begin."

They were together for 10 years, until a fateful night in 2010, when she and her then boyfriend, a cellist, stopped on their way home to grab a bite at a train station cafe.

Kym recounts how she normally sits with the strap of her violin case around her ankle, but her boyfriend persuaded her to pass it to him because she looked uncomfortable.

Thus, they did not notice when it was lifted by three thieves who, at that point, had no idea of its value or the distress its loss would cause.

It would be three years before the violin was recovered, during which the police would chase several false leads, including one in Bulgaria, and the real thieves were arrested. One was jailed for four years, while his teenage accomplices were sent to youth detention centres.

During this period, Kym sank into depression, made worse by criticism in the press that she had been careless to take public transport with a million-pound violin.

She stopped playing and her career suffered, with a prestigious record deal fizzling out.

When her violin was recovered, she could no longer afford to buy it back from the insurance company. It was sold at auction and now belongs to another musician, who plays in a consortium.

Kym, who did not speak directly to the press during this period, decided last year that she wanted to reclaim her story.

"I wanted to put the record straight, to draw a line in the sand and take ownership of my life."

Much of her life, she says, has been marked by passiveness. In her family, she and her sister bowed to their elders and never began meals until after their father, a mechanical engineer, had finished.

This subservience persisted as she passed from teacher to teacher - her first regarded her as a trophy, "a little diamond" to be "polished".

When she was 11, she developed anorexia after an older girl saw her eating pasta and remarked: "Nobody wants to see a fat performer."

The school, she says, was aware of her eating disorder, but a tutor warned her to hide it. "It will kill your career," she was told.

Writing the book helped her realise the subtle ways in which she, as a female and child performer, had been conditioned to relinquish control over her life. "Writing gave me the strength to recognise that it's an incredibly important thing to listen to your gut instinct," says Kym, who is single. "Without that, what are you?"

She is slowly returning to the world of music. She has a new violin, an Amati which she is learning to love, and is doing a series of festivals for music and literature around Britain over the next few months.

Putting her experience down in words has been cathartic, she says.

"The most unexpected thing about writing the book was discovering that I had a voice outside of music and the violin.

"What I've learnt is that we have such little control over our lives. But what you do have some control over is how you deal with things and how you move forward."

•Gone ($30.98) is available at major bookstores.