BEIJING • Sunshine and playtime are not the hallmarks of Cao Wenxuan's stories for children. Instead, they are about mass starvation and displacement, flooding, plagues of locusts, and mental and physical disabilities.

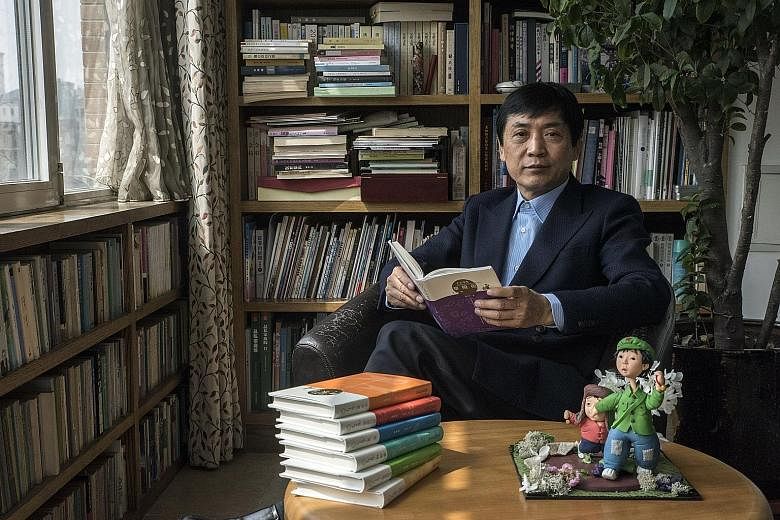

Yet the 62-year-old is among the most beloved writers in China.

Last month, he became the first Chinese author to receive the Hans Christian Andersen Award, which is regarded as the most distinguished international honour for children's literature. He shared the prize, handed out every other year, with German illustrator Rotraut Susanne Berner.

"Cao Wenxuan's books don't lie about the human condition," the International Board on Books for Young People said in announcing the award. "They acknowledge that life can often be tragic and that children can suffer."

At the core of the stories are his experiences growing up in the eastern coastal province of Jiangsu in the 1950s and 1960s, an era of social upheaval and political tumult throughout China.

In his apartment in the Haidian district here, he said his memories of those experiences continued to be his greatest asset.

He said: "China has given us so many heartbreaking stories. How can you avoid writing about them? I can't sacrifice my life experience in order to make children happy."

In his own childhood, he said, there was not much home-grown children's literature. In China then, the concept of literature for children was relatively new, dating to the early 20th century, when translated stories by foreign children's authors began to appear along with local children's works including the fairy tale Ye Sheng- tao's The Scarecrow and Bingxin's Letters To Young Readers.

Through his father, an elementary school principal, Cao said he read some of those stories, Soviet children's literature and Chinese modern literature. He says Lu Xun, a leading writer and social critic, had the greatest influence on him.

As Cao approached adolescence, political tensions in China were escalating, culminating in the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Schools were closed for many years.

The young Cao travelled the country as part of a movement in which young activists were encouraged to spread the message of revolution. But as the student groups, known as the Red Guards, wreaked havoc on the lives of intellectuals, officials and others, he said he was one of many students who held back.

"I was only 12 or 13, we didn't do much. We weren't violent," he said.

"All we did was wear red armbands and write dazibao," he added, referring to the "big character posters" that spread political messages during the period.

Before long, he returned to Jiangsu and resumed classes. As part of the larger upheaval, some of the top Chinese language and literature teachers in nearby Suzhou and Wuxi had been sent to work at his rural school.

As a result, he said, "the Cultural Revolution years were the best education I received". Later, as the movement was winding down, he enrolled in Peking University, where he is now a professor of Chinese language and literature. He published his first short story for children in the 1970s and has not stopped writing since. By his own count, his publications number more than 100 works - novels, academic texts, short stories, essay collections and picture books.

The chaotic years of the Cultural Revolution form the backdrop for many of his stories. His 2005 book Bronze And Sunflower is about the friendship of a girl, Sunflower, who follows her father to the countryside, where he has been sent to do hard labour, and Bronze, a boy unable to speak.

Cao insists that the Cultural Revolution is "merely a setting, not the main subject" of his books. Still, some say his straightforward descriptions of life then are needed now more than ever. In schools today, children are taught only officially approved versions of what, for their parents and grandparents, was an intensely formative and frequently traumatic time.

Today, children's literature is a large and profitable industry in China. Cao and other prominent children's authors have benefited from the rapid expansion of the middle class and a growing obsession with children's education.

Cao's novel Straw Houses is estimated to have sold more than 10 million copies in China. Four of the top 10 richest Chinese authors last year wrote literature for children or young people, according to the newspaper China Daily.

Although Cao has won several important prizes at home, his work has not been without controversy. He has been criticised for promoting outdated gender stereotypes: Boys in his stories are often bigger and stronger, and girls are weaker and more prone to tears. "It's the same in Western children's literature," he said.

But as he has grown older and more experienced, he said, he has become firmer in his belief that, above all, children's literature should provide "a good foundation for humanity and a correct and accurate moral outlook".

That is why, he said, he will continue to write about growing up in China during the Mao years, even if that time feels far away to many children.

"The world is always changing. Fashion trends change, but the fact of people wearing clothes doesn't change. That's what I'm interested in, the continuity. It doesn't matter what the setting is, universal values and humanity always show through," he said.

NEW YORK TIMES

•Straw Houses (bilingual) is available for order from Books Kinokuniya at $15.93; the English version of Bronze And Sunflower is available at $17.49.