Some would say that it takes a major international award to help a country write a new chapter in the literary arts.

Those who think that way are looking over their shoulders at how Malaysian writers Tan Twan Eng and Tash Aw put writing from their country on the world map by winning major international prizes in the last 10 years, awards which also jacked up their book sales.

Penang-born Tan gave Malaysian fiction its biggest recent success when his World War II novel The Garden Of Evening Mists was shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize and, a year later, won the US$30,000 (S$40,000) Man Asian Literary Prize as well as the £25,000 (S$52,000) Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction.

His way was paved by earlier Malaysian literary successes more than a decade old, including Rani Manicka's The Rice Mother, which won the Commonwealth Writer's Prize in 2003, and Kuala Lumpur- born Aw, whose debut novel, The Harmony Silk Factory, won the Costa First Novel Award in 2005.

Aw's most recent and third book, Five Star Billionaire, about immigration from Malaysia, was also longlisted for the 2013 Booker.

-

We are starting to write books that deserve to be read and international recognition seems to be the only way to get a breakthrough in bookstores for Singapore literature.

We are starting to write books that deserve to be read and international recognition seems to be the only way to get a breakthrough in bookstores for Singapore literature.''MR EDMUND WEE of Epigram Books

If you think a book will be read because it's brilliant, that's rubbish... You have to cultivate contacts and critics, be plugged into the publishing scene.''SINGAPORE POET ALVIN PANG

Writers need time and space. If they don't get that, you're not going to get more novels, good novels.''CRITIC AND POET GWEE LI SUI

We don't have editors who can stand up to writers and kick a**.''NOVELIST KRISHNA UDAYASANKAR

This has led to international publishers becoming more receptive to acquiring manuscripts from or about Malaysia, which, in turn, leaves more writing from the country eligible for major overseas awards. For example, the Man Booker is open only to novels originally written in English and published in the United Kingdom in the year of the prize.

To that end, Singapore publisher Edmund Wee is this year starting a new annual prize to encourage fiction writers and select the best for international competition.

But all this begs the question of why no Singaporean writer of fiction has ever achieved international acclaim for literary quality.

Singaporean poets have a significant international presence in the literary world, from headlining at festivals to winning Britain's Foyle Young Poet Of The Year award for poets under 18 (past winners have included Judith Huang and Dawn Lim).

Observers say this is in part because of the prodigious output of poetry in the past 20 years compared with the trickle of fiction from Singapore.

The reason for poetry's prominence here might be that, considering the difference in word count alone, fiction requires a significantly greater investment in time.

This also leads to writers and publishers wanting more of a return on each book of fiction. As a result, it is mostly commercial novels from Singapore that travel overseas.

In terms of sales and impact, the biggest success is Singapore-born American Kevin Kwan's comic romances of the filthy rich, Crazy Rich Asians (2013), optioned for a movie, and its just-released sequel, China Rich Girlfriend.

Representatives of two international publishers and a literary agent who has been representing Asian writing for more than a decade - they declined to be named - say that while commercial fiction from Singapore is marketable, literary fiction is only just coming of age in terms of quality.

So what is holding Singaporean writers back? First - a point so seemingly mundane that it is easy to be overlooked - is the lack of qualified literary editors who can be counted on to help writers shape work of quality. This goes beyond spell-checking and copy-editing and down to helping writers refine their concepts and narrative structure - expertise that comes at a cost of at least $100 an hour, a price that no publisher or author in Singapore is currently willing to pay.

"We don't have editors who can stand up to writers and kick a**," says novelist Krishna Udayasankar, 37, creator of the best-selling Aryavarta Chronicles fantasy series published by Hachette India, and a Singapore permanent resident.

So currently, the editors in demand are all writers in their own right - poets Alvin Pang and Gwee Li Sui, for example - who do this out of appreciation for fellow authors, giving up time they could use to focus on their own art.

The second weakness is that given the small local market, many books depend on official funding and not all the writers can expect it: Consider the National Arts Council revoking the $8,000 grant given to politically themed graphic novel The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew, which has already won an international publishing contract with Pantheon in the United States.

Professor Robin Hemley, director of the writing programme at Yale-NUS College, says: "One can't, on the one hand, promote Singaporean writing and, on the other hand, impose subtle and not-so-subtle restrictions on writers and think that won't have an impact. It's precisely the kinds of books that tend to make bureaucrats nervous that garner international attention."

Says Mr Fong Hoe Fang, 61, of Ethos Books, referring to Khalid Hosseini's novel of life in strife-torn Afghanistan, which was, of course, written by a US-based writer and published in America: "We're pushing people away from writing about the country and its problems. Look at novels such as The Kite Runner and how successful that was."

Of the Singaporeans who have recently made credible successes overseas, most operate outside the system. Short story writer O Thiam Chin's collection, Love, Or Something Like Love, was longlisted for last year's Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award and the book was brought out by Math Paper Press without an arts council grant. Last year, Australia-based Balli Kaur Jaswal was named one of The Sydney Morning Herald's best young novelists, but her book, Inheritance (Sleepers Publishing, 2013), was written while on a David T.K. Wong Fellowship awarded by the University of East Anglia.

Gwee, 45, says: "Writers write because they are compelled to do so. You can't force the compulsion." He adds that the problem in Singapore is that writing relies on official patrons and that tends to promote self-censorship. He would like to see more corporate patrons supporting authors - anything from a five-figure handout to a reserved table at a coffee shop and free drinks.

"The key is to help writers make writing their full-time job," he adds. "Writers need time and space. If they don't get that, you're not going to get more novels, good novels."

MARKETING SAVVY NEEDED

This is not to say that the quality of fiction-writing here has not grown, or that official funding has not helped to sow the seeds.

If there is more and better fiction coming out of Singapore now than 20 years ago, this is because of more investment in the literary arts, both from official sources and small presses dedicated to bringing out local writers.

Ethos Books, Epigram Books and Math Paper Press invest in local literature at a cost which is defrayed by arts council grants or by other paying projects. Ethos Books and Epigram Books offer pagesetting services, while Math Paper Press is supported by the founder's bookstore, BooksActually.

There has always been little money in literary fiction, which is why the output of the 1990s was limited. It included brilliant writers such as the late neurosurgeon Gopal Baratham and lawyers Daren Shiau, Claire Tham and Simon Tay - but all concentrated on bread- and-butter careers over literary production.

Writers from Japan's Haruki Murakami to poets Pang and Gwee point out that writing novels is akin to running a marathon, requiring intense effort sustained over a long period of time. Poetry is more like a 100m dash - neither is superior to the other, but one form requires more time and dedication. And this time could go into work that pays better.

Recognising that writers and publishers need to make a living, the arts council offers a Creation Grant - formerly Arts Creation Fund - giving $26,000 to writer Felix Cheong, for example, so he could write his collection of short fiction Vanishing Point, published by Ethos Books in 2012.

Arts council funding for the literary arts has more than tripled, from more than $1 million in the 2010 financial year to $3.44 million the last financial year, spent on publishing grants, writing residencies and scholarships, among others things.

There are more Singapore writers than ever putting out short story collections or working on their first novel, including Amanda Lee Koe, whose 2013 debut collection Ministry Of Moral Panic (Epigram Books) won the Singapore Literature Prize last year.

Mr Wee, 63, says: "We are starting to write books that deserve to be read and international recognition seems to be the only way to get a breakthrough in bookstores for Singapore literature."

His Epigram Books Fiction Prize offers a $20,000 advance on royalties and publication for the best submitted manuscript, with the aim of finding a Singaporean novel good enough to co-publish in London and get onto the Man Booker longlist within five years.

To date, home-grown literary fiction has rarely been a bestseller - 2,200 copies of Ministry Of Moral Panic sold in Singapore since 2013 versus more than 100,000 copies of E.L. James' Fifty Shades Of Grey. Asian literary writing in English is relegated to speciality shelves rather than front-of-store displays unless one or more authors make headlines.

Mr Wee is not the only one who thinks that international marketing and recognition is critical for Singapore writing to make the next leap.

Pang, 43, says: "If you think a book will be read because it's brilliant, that's rubbish. That's not how the world market works." He reads and judges submissions for major literary journal Granta and is involved in prizes such as the upcoming A$5,000 (S$5,000) Vice- Chancellor's International Poetry Prize offered by the University of Canberra. "You have to cultivate contacts and critics, be plugged into the publishing scene. So who succeeds? The people who leave."

Malaysians Aw and Tan, for example, studied in London and have agents who market their work around the world.

Pang's poetry has a significant overseas following and he is a familiar face at international festivals. He has led a delegation of Singapore poets to the Austin International Poetry Festival in 2002 and was featured at the 2003 Edinburgh Book Festival.

In part because of this sort of exposure, Singaporean poets have had critically acclaimed collections acquired by elite publishers overseas. Sydney-based Eileen Chong's Burning Rice was shortlisted for the 2013 Prime Minister's Literary Awards in Australia.

The arts council and the National Book Development Council of Singapore have, in the past few years, taken local publishers to major overseas book fairs in London and Frankfurt to network, but publishers say there has been little interest so far in their literary titles.

What is needed is for publishers and writers of Singapore literary fiction to become more savvy at marketing themselves. Take the case of The River's Song by Suchen Christine Lim, published by London- based Aurora Metro Books last year. The publisher recently took advantage of the influential Kirkus Reviews' Kirkus Indie programme to support small presses. Under this service, publishers pay for a review from "experienced professionals who honestly and impartially evaluate the books they receive".

The gamble paid off when Lim's novel earned a starred review last month. This will make it easier for her books to enter overseas bookstores and possibly, eventually, the notice of an awards committee.

Observers such as Prof Hemley think it is only a matter of time before a work of fiction from Singapore is noticed by the literary powerhouses of New York and London. "I do think Singaporean literature has been coming on strong of late and you should give it time," he says.

"Winning literary prizes is a mix of timing, luck and good writing," agrees Mr Wee. "All we need is that one breakthrough."

•Why do you think Singapore fiction has yet to win international acclaim? Write to stlife@sph.com.sg

Writers to watch

What makes a Singapore writer? Of the fiction writers to watch, two were born here or to Singaporean parents and now reside elsewhere, while another is a new citizen.

PP WONG

PP Wong, 33, is British-Chinese but born to Singaporean parents. She studied at Methodist Girls' School and Anglo-Chinese Junior College and spends much of her time here with her family.

Her debut novel, The Life Of A Banana, published by Legend Press in Britain and Monsoon Books in Singapore, draws on her experience of racism and bullying while at school in London.

It was longlisted for the Bailey Women's Prize for Fiction this year, but lost out to Ali Smith's How To Be Both.

Wong is working on her next book and also helms an influential writing group, Banana Writers, for Asian writers to discuss their experiences and share advice on finding editors, agents and getting published.

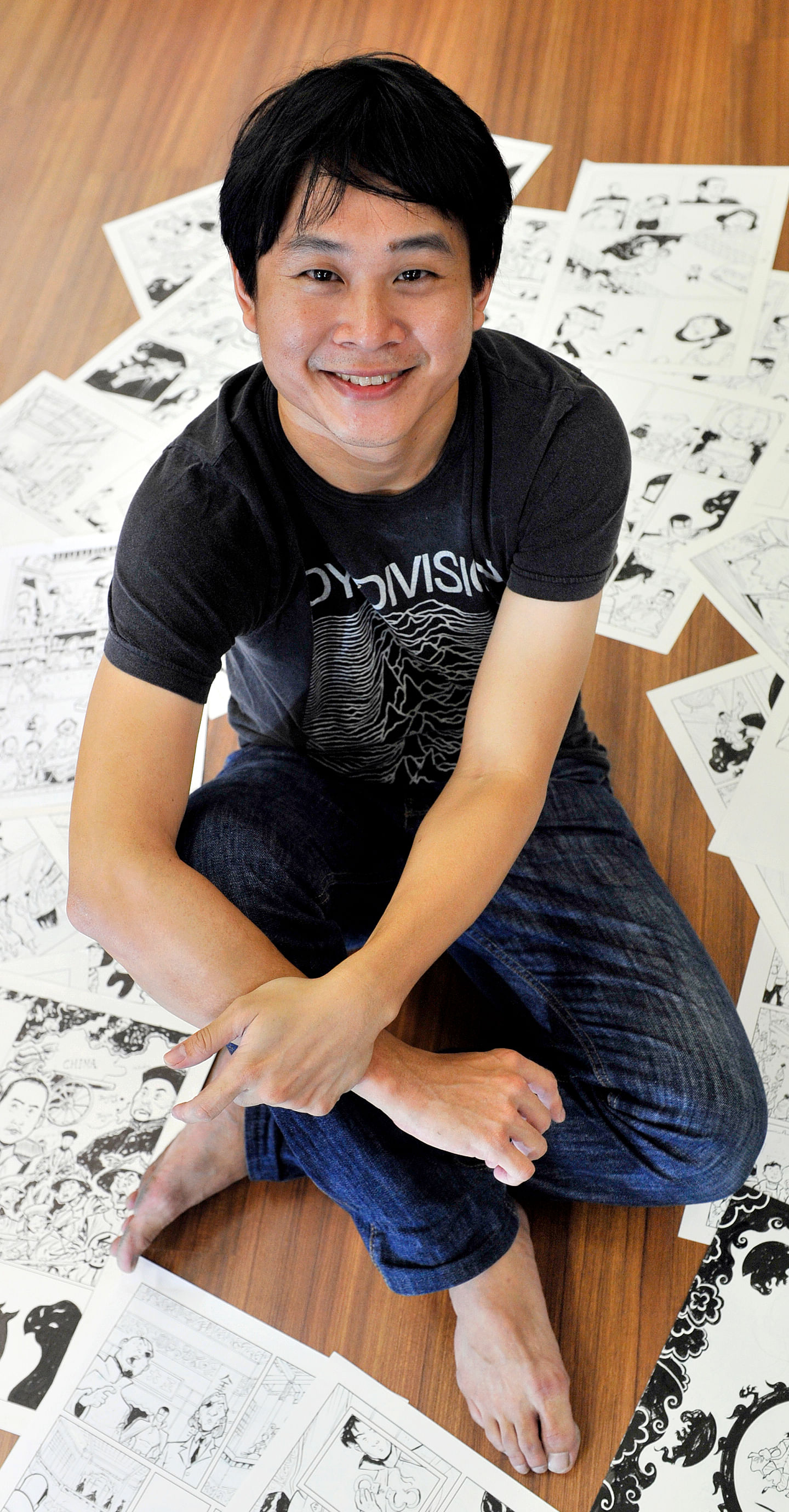

SONNY LIEW

Malaysia-born Singapore citizen Sonny Liew, 40, is renowned internationally for his storytelling and drawing skills and has been nominated three times for the Eisner Awards, the comics industry's equivalent of the Oscars.

He received the National Arts Council's Young Artist Award in 2010 and is the lead artist on DC Comics' Doctor Fate monthly series.

His newest solo effort, The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, was published by Epigram Books in May. The politically themed graphic novel examines the past 60 years of Singapore's history through the life of a fictional artist. It has garnered positive international reviews since The Straits Times broke the news in May that the National Arts Council withdrew an $8,000 publishing grant for the work, citing its "sensitive content".

The international edition will be brought out by Pantheon in the United States next year.

BALLI KAUR JASWAL

The Singapore-born, Australia-based author of Inheritance (Sleepers Publishing, 2013), a pitch-perfect family drama about a Punjabi family in Singapore, was last year among four writers named The Sydney Morning Herald's choice of best young Australian novelists.

Balli Kaur Jaswal, 32, who is married, began Inheritance while on the £25,000 (S$52,000) David T.K. Wong Fellowship for writing at the well-known University of East Anglia.

She was the first Singaporean to win the award and is working on her second novel, a dark comedy set in a Punjabi immigrant enclave in London.