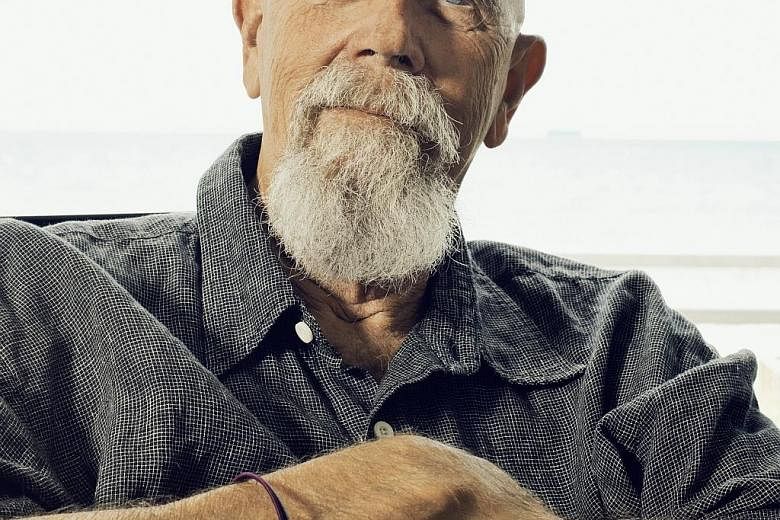

NEW YORK • Chuck Close and other artists used to sit around bars such as the Cedar Tavern and Max's Kansas City and talk about art.

"I have more conversations today over what we're going to do to protect our spouses, our children, our work," Close said.

At 77, he is among a critical mass of prominent - and profitable - artists in their twilight years (including Claes Oldenburg, 88; Ed Ruscha, 79; and Gerhard Richter, 84) facing important decisions about how to secure their creations and provide for their heirs just as the exploding market has significantly increased the value of their work. And the art world hopes to cash in on it.

"You have the greatest number of artists there has ever been who are wealthy from their own creative work and have to make provisions for the posthumous stewardship of that work," said Ms Christine J. Vincent, project director for the Artist- Endowed Foundations Initiative at the Aspen Institute, which helps private foundations created by visual artists. "More and more entities are getting involved in servicing it."

Sotheby's just hired Ms Christy MacLear, chief executive of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, in an attempt to start managing artists' careers, estates and foundations, a role historically played by galleries.

The potential revenues in managing artists can be substantial in fees for services, in sales and in business worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Cy Twombly Foundation, for example, has assets of US$1.5 billion (S$2.1 billion).

Handling artists not only allows for control of their remaining unsold work, but it also offers access to their catalogs raisonnes, a thorough accounting of every piece by the artists and who owns them - which can lead to future sales.

"This is a field that's growing fivefold," Ms MacLear said, with "people considering what their legacy is".

Those on her potential wish list: Frank Stella, 80; John Baldessari, 85; and baby boomers such as Eric Fischl, 68.

"How hard it is to contemplate your own death," Fischl mused in an interview. "There's taxation and whether it's better to keep the art and sell it off a little at a time or to try to sell it off before you die and put the money in a foundation - it's hugely complicated. I find it incredibly daunting."

He said his own galleries have not navigated such terrain.

Ms Amy Cappellazzo, a chairman at Sotheby's, said the effort to manage artists was part of the company's continuing effort to transform itself into a full-service operation. "We're not an auction house," she said. "We're an art business."

Auction houses are not permitted to show at art fairs, which leaves today's largest transactional arena off-limits. And many dealers say auction houses will not be able to serve artists and their legacies the way galleries do.

"Their interest is selling," said Mr Arne Glimcher, chairman of Pace, which represents living artists such as Close and Kiki Smith. "Making money is a long-range process with us."

The care and feeding of artists, dealers say, is also a high-maintenance job.

"Living artists have enormous personal needs," Mr Glimcher said. "There are constant conversations. We're a daily support system."

Sotheby's executives say that galleries are not necessarily well- equipped for the long-term planning required by today's successful artists, whose holdings can include land or foundations that give philanthropic grants.

"Dealers' first calling is to sell the work by artists," Ms Cappellazzo said. "They don't often get involved in matters of legacy or wishes of the heirs."

But many artists consider auction houses the enemy because they can inflate prices and hurt an artist's reputation if something fails to sell.

"The last thing I want messing around with my career is an auction house," Close said. "That might be the worst thing for the artist."

This new model also raises ethical questions: Could the auction house show preferential treatment to its artists by putting them on catalogue covers, for example, to increase their value and by steering an artist's work into auction sales, rather than into prestigious museum collections?

"There is the inherent conflict of interest," said Mr Edward Dolman, chairman and chief executive of Phillips auction house, which is not pursuing artist management.

The auction house's "emphasis is to make sales", he added, "which may not be in the interest of the artist or the artist's estate".

He also questioned why an artist would enter into an exclusive arrangement with any one house.

"The great advantage of the market is to play Christie's, Sotheby's and Phillips off against one another," he said. "Why would you bind yourself to one auction house for advice you can get for free anyway?"

NYTIMES