In an Anatolian village "forgotten by God and the government", people keep disappearing - the barber, for instance, or the village belle.

Miles away, in an unnamed Turkish city, the novelist writing all this waits at the barber's for a haircut.

This is the phantasmagoric world of Shadowless, the 1995 cult novel by acclaimed Turkish postmodern writer Hasan Ali Toptas, which has recently been translated into English for the first time.

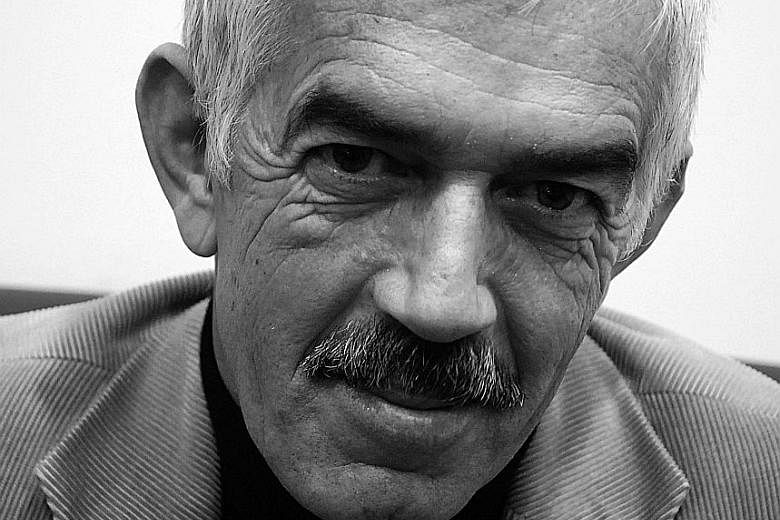

Toptas, 58, won the Yunus Nadi Novel Award, Turkey's oldest surviving literary competition, for Shadowless, which was also adapted for film in 2008.

In 2015, Bloomsbury Publishing began to put out Toptas' work in English, starting with his latest novel Reckless (2013) and followed in April this year by Shadowless, translated by Maureen Freely and John Angliss.

In an e-mail interview in Turkish, Toptas says the seed for Shadowless was planted by a conversation he overheard in a coffeehouse, about whether a snake could swallow its own tail.

This gave his narrative its circular structure, he says. "The architecture of the novel took the form of a snake swallowing its own tail."

The Ankara-based father of two is often compared with German writer Franz Kafka for his strange, troubling works, a comparison he gently rebuffs. "One Kafka is enough for this Earth - what use would a second be?"

He allows, however, that his "spirit is neighbours" with some other writers. The South African writer J.M. Coetzee, for instance, is "a distant neighbour" while Mexican author Juan Rulfo has, "for as long as I can remember, lived on the same street (as me)".

In the hazy, surreal pages of the metafictional Shadowless, people perish suddenly, meld into one another or vanish into thin air.

"In the region in which I live, people regularly disappear," says Toptas. "Sometimes, it is a mystical disappearance, an ecstatic state in which they are said to have 'joined the saints'. Sometimes, these disappearances are carried out by the hands of the state or by those of a series of dark powers. Our history is filled with these types of cases that have never been explained."

Shadowless is possessed of an uncanny, dream-like quality.

"In Turkish, dreams have the meaning of our minds pointing out things we don't want to see while we are asleep," he says.

"They are films that we cannot direct, but which we are watching."

He does not remember his own dreams, with one notable exception: While working on his new book Birds Go To Mourn, he dreamt about writing the novel and, after waking, wrote the dream into it.

"My mind continued writing the novel in the dream in some way, or the novel made me write a few pages of itself in a dream."

It is ever more pressing in these times of conflict, he says, that more novels and poetry from the Middle East be shared with the rest of the world, to help them understand the region.

"Most literature comes from places where there is pain, unhappiness and tears," he says.

"For years, the Middle East has been a lake of blood. The bottom of the Mediterranean and Aegean is filled with human corpses.

"It is, of course, not sufficient just to understand. The bleeding wound there is a wound on humanity and, beyond understanding it, we must urgently unite for a solution."