NON-FICTION

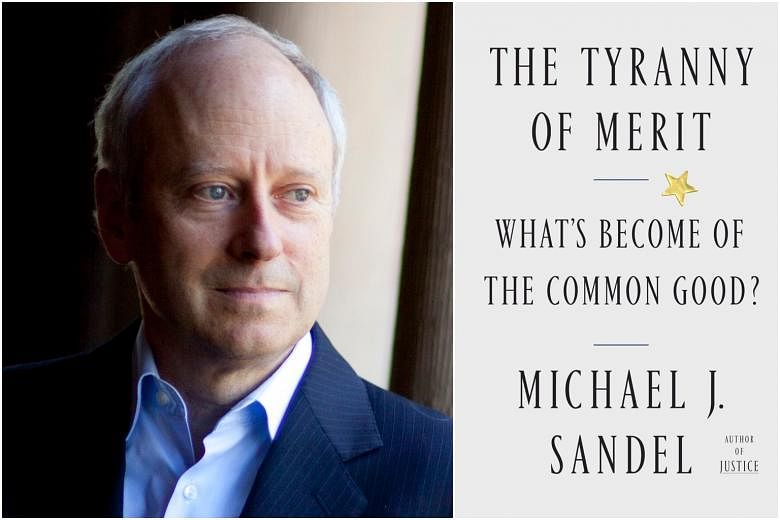

THE TYRANNY OF MERIT

By Michael J. Sandel

Farrar, Straus and Giroux / Paperback / 272 pages/ $24.72 / Available at bit.ly/TyrannyMerit_MJS

4/5

Meritocracy, Singapore's sacrosanct national ideology, was meant by its creator as a dystopia.

When British sociologist Michael Young coined the term in 1958, he imagined a fictional society that had overcome class barriers, only to become obsessed with measuring merit.

Far from being fair, he thought this society would create a new aristocracy of talent, resulting in social inequality that would lead eventually to revolt.

If this seems prescient, it is because Americans are living Young's dystopia now, says Harvard University professor Michael Sandel.

But are one's achievements ever fully his own? After all, winning the lottery of birth plays no small part in people's successes.

For instance, affluent families can afford to give their children more resources and even pull strings to get them admitted into supposedly meritocratic elite universities, Sandel notes.

He readily admits this problem is not new, but argues that answering it is necessary to understanding how meritocracy has proved so seductive an ideology.

In his seminal A Theory Of Justice (1971), the influential liberal philosopher John Rawls argued that since people cannot control the circumstances of their birth, a just society needs to ensure fairness through equality of opportunity. In other words, if there is a problem, it is not with meritocracy, but rather with insufficient meritocracy.

Here, Sandel asks a more novel question: Would even the perfect meritocracy be just?

For him, the answer is no.

Sandel's strength is not in punctilious exposition, but in his knack for breathing life into philosophy by applying it to today's happenings.

The more meritocracy becomes a fact, he warns, the more elites will feel they deserve their high station in life and disdain those at the bottom, who are made to feel they deserve to be there.

The most current - and overused - of these examples is, of course, the polarisation of the United States.

It is now a familiar liberal post-mortem of the 2016 - and, for some, this year's - election: Outgoing US President Donald Trump drew on lower-wage, less-educated Americans who resented being told by liberal college-educated elites that they deserve to be where they are.

Other examples will seem more applicable closer to home.

For instance, Sandel criticises the idea that only the "best and brightest" should govern as "a myth born of meritocratic hubris" - one that ignores the need for practical wisdom and deliberation, not just technocratic expertise.

He was referring to former US president Barack Obama's Cabinet of Ivy League college alumni, but could easily have been speaking of many other countries' well-credentialed political leadership, Singapore's included.

Similarly, Sandel convincingly argues that the dark side of meritocratic thinking is a "rhetoric of responsibility", where politicians suggest that poor people who have not worked hard enough do not deserve help.

Again, he refers to Republicans and Democrats, but one might apply the same thinking to Singapore, where "means-testing" and self-reliance are tenets of policy.

This is not the first time Sandel, dubbed the "most relevant living philosopher" by Newsweek magazine, has managed to fill old bottles with new wine, as the millions who watched his Harvard online course Justice will attest.

Though US-centric, the examples in his book are relatable enough for Singaporean readers.

Perhaps the most important of his warnings is that meritocracy erodes the common good.

It erodes the dignity of low-wage work, which it took a pandemic for many to deem "essential". It erodes social bonds by pitting individuals against one another.

To counter this, Sandel calls for a reconsideration of the kinds of work society esteems and of what citizens owe one another.

For this to happen, beyond equality of opportunity, there needs to be equality of conditions.

These are lessons worth pondering for Singapore, which may be especially close to reaching Young's bleak vision of a perfect meritocracy.

If you like this, read: This Is What Inequality Looks Like by Teo You Yenn (Ethos Books, 2018, $27.82, available at bit.ly/WInequalityLL_Teo), which explores one of the dark sides of meritocracy in Singapore through a deep ethnography of low-income families living in rental flats.