Dakota childhood filled with ghosts, games and gods is fodder for writer Wong Koi Tet

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

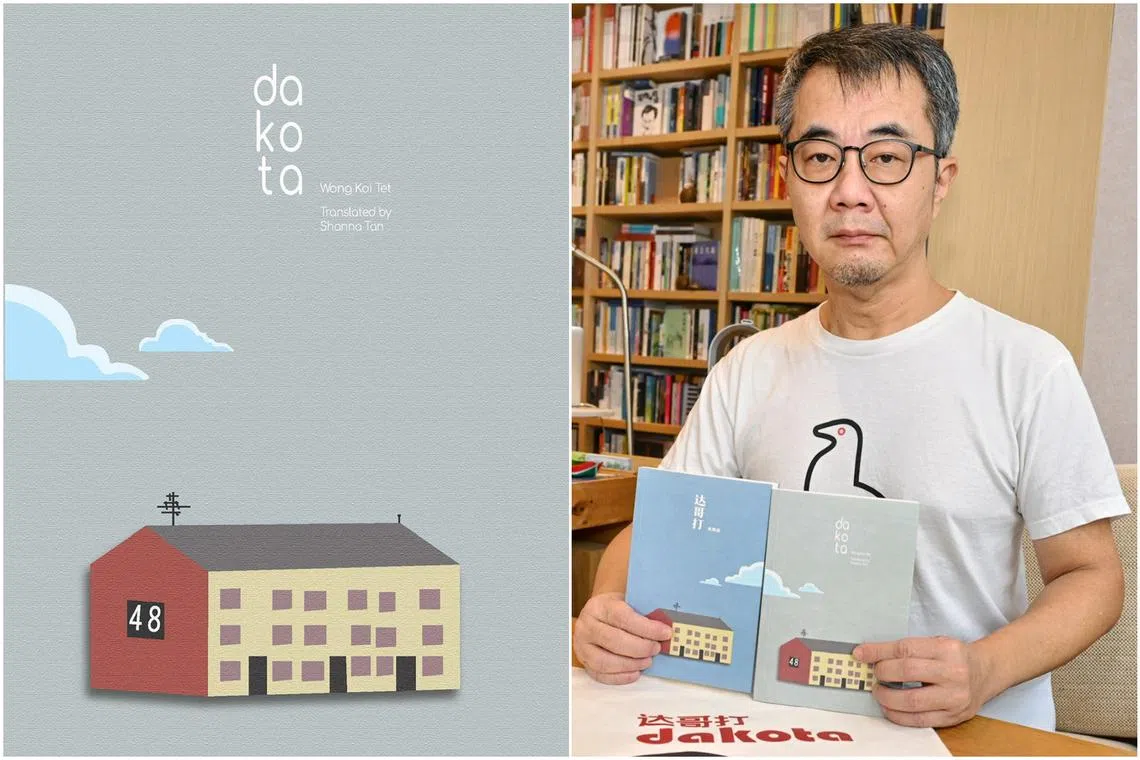

Chinese-language writer Wong Koi Tet says he has never left Dakota and has written about his 1970s and 1980s Singaporean childhood in an expanded version of his book Dakota.

PHOTOS: CITY BOOK ROOM, DESMOND WEE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Writer Wong Koi Tet is a true-blue Dakota boy. Born in the year that Old Airport Road Food Centre opened, the former Dakota Crescent resident now lives with his mother in Cassia Crescent – a stone’s throw from his demolished childhood home.

His cobbler grandfather used to ply his trade on the second floor of the food centre.

For the first 27 years of his life, Wong heard ghost stories by Dakota’s murky longkau (Hokkien for drain), witnessed his neighbour get possessed by the deity Nezha and caught monitor lizards for an elderly neighbour’s lunch. It was in Dakota that the 51-year-old felt the first pangs of lust and love.

The red-bricked flat is now gone. In its place is a towering glass condominium complex.

But Wong has kept the memory of his childhood alive in a collection of personal coming-of-age essays – Dakota – that was first published in Chinese in 2018 and won the Singapore Literature Prize for creative non-fiction.

Newly translated by the rising Singaporean translator Shanna Tan

“I’ve never left,” says Wong, who means this literally. Unlike many of his former neighbours, Wong’s parents refused offers to move to other areas such as Tampines and insisted on staying in Dakota. Metaphorically, too, as Wong says that there is no other place that inspires such deep feelings as his childhood home.

For this interview, the writer of genres as varied as fiction, poetry and essays wears a T-shirt bearing his illustration of a pigeon playground, which has become a symbol of the historic neighbourhood. The book, too, is peppered with his illustrations.

Wong says he can call up memories of his childhood and hardly referenced photographs or other objects in the writing of his book.

“When I am writing Dakota, I seem to have this ability to project myself into a state of mind that feels like returning to the setting of my childhood.”

The former Lianhe Wanbao crime reporter adds: “Memory is a very strange phenomenon. Sometimes the door will open, you take a glance – and you see the clinic under the 10-storey flat.”

He has been writing about his childhood home since his family was forced to leave in 2000, more than a decade before the Save Dakota Crescent campaign from 2014 thrust the issue into the national spotlight. Then, Wong was teaching creative writing at Nanyang Technological University, and would write alongside his students on topics about memory.

Dakota was thus born, composed of delightful little vignettes evoking a bygone 1970s and 1980s Singapore where friendships were forged at the playground or the now-gone Gay World Amusement Park.

In a cheekily titled essay My High-Tech Childhood, Wong lists the film camera, VCR player, washing machine and radio.

His prose is often punctuated, when one least expects it, by a dazzling image. He has an eye for the peculiar memory, as when he describes an unforgettable sight in his washing machine: “Spinning slowly among the clothes was the Tua Pek Kong statue from the altar. For the first time since descending to the mortal world, he was untainted by a single speck of dust, gleaming with a child-like pureness.”

Wong explains his writing process: “To borrow the language of photography, I begin by focusing on something small and slowly zoom out to a macro perspective. If the scene that I write comes across as clear, the emotions will naturally follow.”

Given the strong public reaction to the impending demolition of Dakota in 2014, the Government decided in 2017 that elements of the old neighbourhood from 1958 – which predates the Housing Development Board (HDB) – can stay.

Asked what he thinks, Wong appears not overtly nostalgic about appearances.

“I didn’t have very strong feelings – my childhood home has already been demolished,” he recalls. “To physically conserve these things, you preserve only a shell – the things and the people in them have disappeared. It’s a crude reality of life.”

The fact that the neighbourhood was named after the crash of a Dakota DC-3 aircraft near the area, for him, foreshadowed the premature demise of his childhood home.

“Even during the 1990s, we could sense that the time for this place was coming to an end. Dakota has always been an interim housing project.”

Fair warning to Anglophone readers, the shape of these essays is not the typical writing one finds in a non-fiction title.

Wong says: “English readers don’t really understand sanwen (Chinese prose or essays) and can only use non-fiction as a concept to understand – but it’s more than that. It’s difficult to translate sanwen, and I had rejected many translators who were interested in the project because I felt that sanwen is very intertwined with the writer’s personality.”

But Tan’s lengthy cover letter to Wong asking to translate the book moved the writer – who agreed to let the translator, then without a single book on her resume, work on this personal project.

Tan has had her own ideas – rendering some of the speech in a vernacular that feels immediately resonant with any reader familiar with Singapore.

For this new translation, Wong has added six pieces on topics such as ghosts and childhood games to both the Chinese and English editions.

The initial self-published Chinese-language print run of 500 books sold out, which makes the release of this book a treat for Chinese-language readers too.

Wong says there are more stories to be mined. He is still writing about Dakota today and it does not sound like he will ever want to stop writing about his childhood.

Musing over the possibility of another expanded edition, he says: “It’s fun – an ever-expanding, never-ending story about Dakota.”

Dakota, which comes in Chinese and English editions as well as a bilingual box set, is available from the publisher City Book Room ($25 a book) and from all major bookstores.