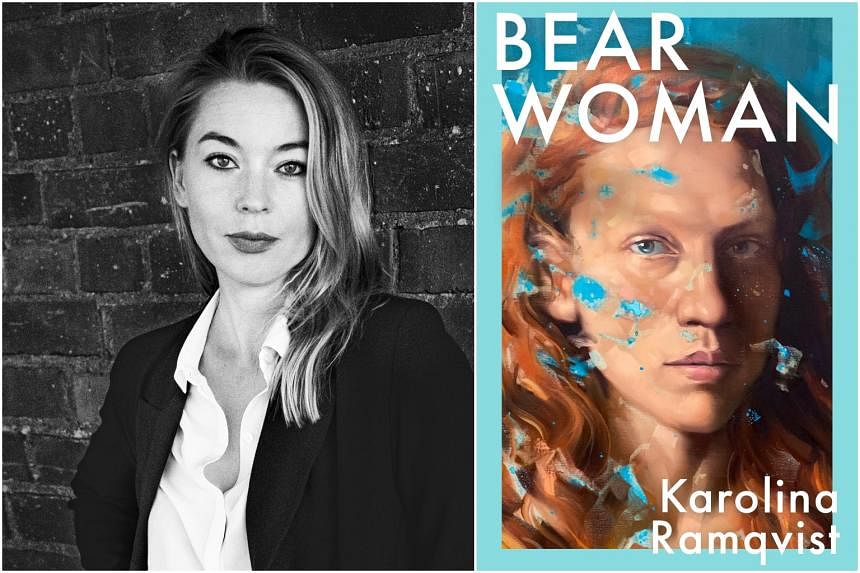

Bear Woman

By Karolina Ramqvist, translated by Saskia Vogel

Fiction/Manilla Press/Paperback/337 pages/$27.58/Available here

3 out of 5

In Korean mythology, a bear called Ungnyeo transmutates into a beautiful woman after its prayer is answered.

Driven to depression by the lack of a husband, she prays once more and is taken as the wife of a divine king and blessed with a son who goes on to found the nation of Korea.

Compared with the Korean myth, the French bear woman in Swedish writer Karolina Ramqvist's sixth novel is decidedly more human, more corroborated by historical record and much less fortunate.

The same pieces - a man, a woman, a new land, a bear and a child - are there, but they come together in a tragic configuration, happening to French noblewoman Marguerite de la Rocque in a twisted 16th-century parallel to the Korean tale.

After her parents' death, the young Marguerite is left to a scheming guardian and taken on an uncertain voyage across the seas.

To say more would spoil the story, the forward momentum of which relies so much on mystery, but it includes bear shooting and an illicit romance, and should be exciting and gripping in its own right.

It is a shame, then, that its impact is blunted by Ramqvist's telling, which chooses to abjure Marguerite as the obvious protagonist and instead foreground the author's own research process.

She opts to break up the more dramatic episodes of Marguerite's life with extended descriptions of her own as she goes about researching her book - how she Googles a person's image, or her inability to write as she struggles with the ethics of speaking for a girl who in her life was never given a voice.

She implicitly hints at parallels between both women's states of mind, while making sure that readers understand how much of history is lost and how records, especially those written by privileged men, may not have been in the interest of a young girl under the control of a powerful French noble.

These are all valuable messages, but their reiteration quickly wears thin.

The passages slow down the tempo of the book just as readers are getting invested and severs the empathetic link between reader and character that is so important to keeping a novel absorbing.

In some cases, however, it works. Ramqvist is, after all, one of the most influential writers of her generation. Her writing flows easily, is to the point and, at moments, insightful.

A scene where she and her daughter get into an argument in France, which ends with her daughter performing a bittersweet - albeit illegal - act of reconciliation quickens the pulse.

A section relating Marguerite's pregnancy to her own misremembered pain of childbirth is also a welcome surprise.

Most of it, however, is a slow grind, with the book redeemed only by the sincerity of Ramqvist's obsessive reflections and the frankness with which she writes.

Readers come away with the notion that perhaps Marguerite would have been better served with a more straightforward piece of fiction, where the author makes better use of the poetic licence afforded to her to fill in the gaps where history cannot.

If you like this, read: Circe by Madeline Miller (Little, Brown and Company, 2018, $21.95, buy here, borrow here), which retells the story of the enchantress and minor Greek goddess as one of a woman who has to choose between the gods and the mortals she love