Human beings like narratives and try to see patterns in everything around us.

Take a salesperson who may notice that on the past few occasions when she wore red, she seemed to manage to close a deal. So she makes up her mind that from now on, if she's negotiating a big deal, she will wear red.

So it is when it comes to the market. In 1987, there was a big crash. In 1997, we went through the Asian financial crisis. And in 2007, we had the global financial crisis. It is a pattern! The market moves in cycles of 10 years. This year, we are due for a big crash.

However, just as the salesperson would no doubt encounter a meeting when she wore red and yet still didn't manage to close the deal, the market too is unlikely to move like clockwork.

WHAT CAUSES A MARKET CRASH?

A major crash is more likely to happen when valuations are excessive. In a capitalist world, there is a fair value for most things. The fair value for a new building will incorporate the land cost, the cost of the materials and labour and capital used to build it.

Similarly for stocks or companies. The fair value of a company is based on either the assets the company owns or the earnings it is able to generate, which will either be returned to investors or used to grow its business. However, depending on which emotion - greed or fear - is more dominant in the market, the prices of assets may deviate significantly from the fair value.

It is when prices veer too far away from the fair value that we will see a severe market correction, which will then bring prices back closer to fair value.

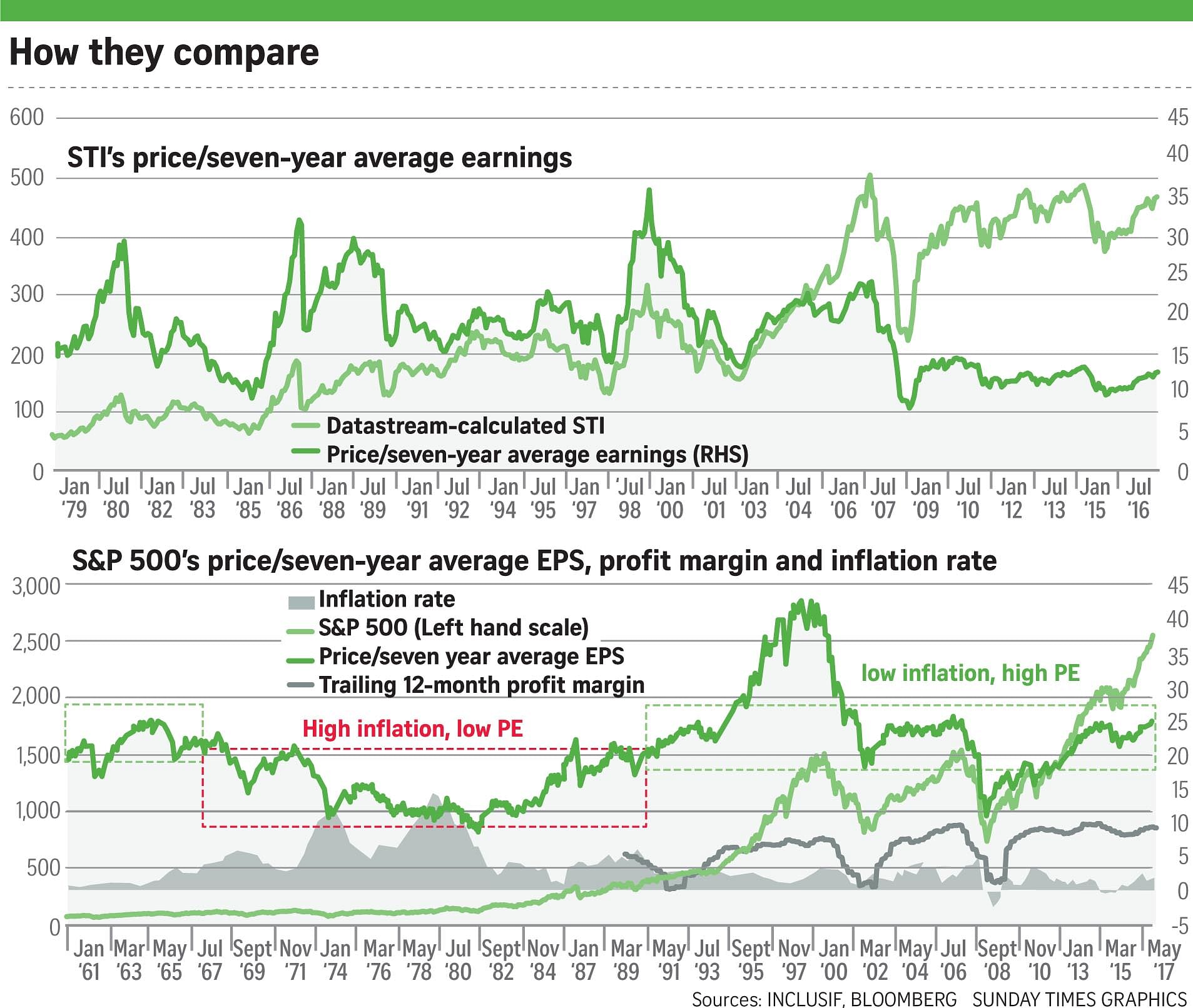

Let's take a look at the chart of the Straits Times Index (STI) as calculated by Datastream going back to 1979. I plotted the STI, which is basically the price of the component stocks in the index, against the seven-year average earnings of these companies.

I used the seven-year average earnings to smoothen out the cyclicality of earnings. Since one measure of fair value is the earnings a company is able to generate, the price can't be too detached from earnings. There has to be a certain range where we would consider the company to be fairly valued.

Over the last 40 years or so, the STI has traded up to a high of 36 times its earnings (price-earnings or PE ratio) and to a low of eight times earnings.

The PE ratio is calculated by dividing the current market price of the stock by its earning per share and is used in valuing companies.

Whenever the PE ratio hit the higher end of the range, the market would correct downwards. Conversely, when the PE ratio sank to the lower end of the range, the index would rebound. As can be seen from the chart, there have been six major corrections in the last 40 years or so - more frequent than once every 10 years!

The PE ratio of the STI has been at the lower end of its 40-year range since the 2007 global financial crisis.

The low PE ratio could be a result of investors' expectations of the lower growth for Singapore companies. But the main point is, the current market PE ratio is not at such a high level to pose a big risk of a major crash.

WHAT ABOUT THE U.S. MARKET?

With markets in the United States scaling record highs, surely a crash is just around the corner? Again, the same principles apply. We have to relate current market price to the earnings.

Another factor to consider is, given current market conditions - low interest rates, low inflation, stable GDP growth, decent profit margins - what is a PE ratio investors are comfortable with?

US asset management firm GMO developed a behavioural model which suggests investors are comfortable with higher PE multiples when interest rates and inflation are low, when GDP growth is stable and when corporate profits are relatively high.

Its model has a 90 per cent fit with the actual movement of the US stock market index, the S&P 500, going as far back as 1925.

I plotted the S&P 500 against its price/seven-year average earnings ratio, inflation rate and profit margins. From the chart, you can see that periods of high inflation have coincided with lower market PEs. Conversely, investors have tended to value the market higher when inflation is low.

While the S&P 500 price index has climbed to uncharted territory, the price/seven-year average ratio is within "normal" range, given the current low inflation, decent profit margin and stable GDP growth environment. In other words, prices are not excessive as yet.

So what would cause a large and more or less permanent decline in the market? That would require an equally large deterioration in profit margins or increase in inflation or some combination.

Without either, any large market decline would be very unusual historically and likely, according to GMO founder Jeremy Grantham, to be temporary.

Mr Grantham is also of the view that a crash in margins (as we had in 2008-09) or a truly dramatic rise in sustained inflation (as we saw in 1979-81) or some powerful combination is improbable, at least in the near term.

In short, with just a fortnight to go before the end of 2017, hopefully we will be able to debunk the myth of 10-year market cycles.

PSYCHOLOGY AFFECTS OUTCOME

But just as the salesperson may feel more confident when she is wearing red, and as a result is more confident and charismatic, which may increase her chances of closing a deal, it may be well that the collective fear of investors may cause a crash at the smallest of trigger.

However, if the above reasonings are sound, then the crash will be temporary - unless inflation rises sharply on a sustained basis and profit margins collapse.

For some guidance, the master of value investing Benjamin Graham has this to say about getting decent returns from the market: "The main need here is for the investor to select some rule which seems to be suitable for his point of view, one which will keep him out of mischief, and one, I insist, which will always maintain some interest in common stocks regardless of how high the market level goes.

"For if you had followed one of these older formulas which took you out of common stocks entirely at some level of the market, your disappointment would have been so great because of the ensuing advance as probably to ruin you from the standpoint of intelligent investing for the rest of your life."

• The writer is the portfolio manager of Inclusif Value Fund, a no-management fee fund (www.inclusif.com.sg).