As China weakened the yuan for a third straight day yesterday, economists were debating the reasons for Beijing's sudden embrace of a market-driven exchange rate.

The dramatic move by China's central bank has sent jitters across global markets and sparked accusations of a "currency war".

Critics have panned the devaluation as just another instance of a slowing economy resorting to currency tactics to prop up the economy by giving exporters an edge over their global counterparts.

A weaker yuan makes China's exports cheaper.

But some analysts argue that the devaluation is China's way of cushioning the yuan from strengthening along with the US dollar after a projected interest-rate increase from the Federal Reserve which may come as soon as next month.

China's push to seek reserve-currency status in the International Monetary Fund's exclusive Special Drawing Rights (SDR) group is also seen as a reason the yuan has been allowed a market-oriented valuation. China is finally living up to its promise of currency liberalisation, they said.

"The change to how the reference rate is set is primarily intended as a move towards greater liberalisation of the forex markets" ahead of the IMF's impending decision on the yuan's SDR inclusion, economist Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics said in a note.

China's economy has been under a cloud since it showed signs of a slowdown in 2012, after years of 10 per cent plus growth. Deceleration set in as productivity declined, in part because investments in infrastructure and real estate did not give high returns any more.

The debt crisis in the euro zone - its biggest market - also hit exports, throwing China off balance.

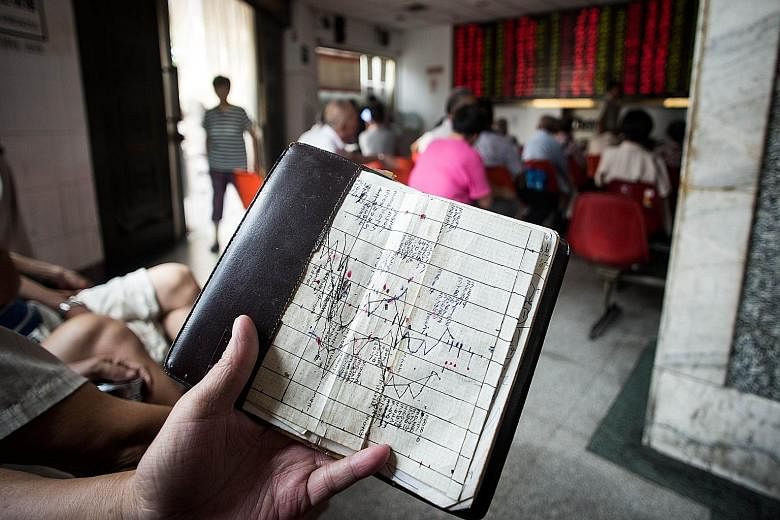

More recently in mid-June, a massive sell-off battered China's equity markets to the tune of US$3.4 trillion (S$4.8 trillion). Foreign investors fled. The government stepped in with massive stimulus and stringent rules to stop the rout.

The market did achieve some stability until second-quarter data released on Wednesday showed industrial, retail and fixed-asset investment growth had come in weaker than forecast. Exports tumbled 8.3 per cent in the same month, their biggest fall in four months.

A Fitch report said it was difficult to separate the depreciation entirely from weak activity data for last month, and from broader concerns over economic growth.

"The direction of movement of the currency highlights wider pressures on the economy."

A weaker yuan could benefit China to a certain extent against its main export markets such as the European Union and the US, Morgan Stanley Research said in a report.

The currency realignment will lower profit margins and exports in the US and should enable China and Asia more generally to export some deflation to the rest of the world, hedge fund manager Stephen Jen was quoted by Bloomberg as saying. "But we have likely seen China breaking off, leaving the US as the sole economy bearing the burden."

However, Goldman Sachs Group said the currency devaluation is designed to cushion the yuan from strengthening along with the dollar after a looming interest-rate increase by the Federal Reserve.

"This is about the Fed liftoff most obviously and further dollar strength," Mr Robin Brooks, chief currency strategist, wrote. "It certainly makes sense for China's policymakers to buy some flexibility ahead of the Fed liftoff, in particular as the fix had become very peg-like in its stability in recent months."

However, Standard and Poor's chief economist for Asia-Pacific, Mr Paul Gruenwald, said the argument that China is weakening its currency to spur exports is not very convincing. He added that the timing is opportune for other reasons.

"China can now say that by moving to a more market-determined rate, it is delivering what the IMF and US Treasury have been asking for," Mr Gruenwald wrote.

IMF member countries are poised to vote later this year on whether to add the yuan to the SDR basket of reserve currencies.

On Tuesday, IMF welcomed the yuan devaluation in a statement saying that "a more market-determined exchange rate would facilitate SDR operations" if the yuan were to be included.

Whatever the reasons, the People's Bank of China yesterday assured the market that there was no basis for the depreciation to persist, and that it will step in when excessive volatility arises.

It has brushed off talk of competitive devaluations across the region. "There's no necessity for China to start currency wars... to gain competitive advantage," said Mr Ma Jun, its chief economist. "If every country tries to devalue its currency, no one will benefit."