The unconventional measures adopted by the Chinese government to stem the recent bloodbath in the nation's stock market have been described by some as desperate but the fact remains, they worked.

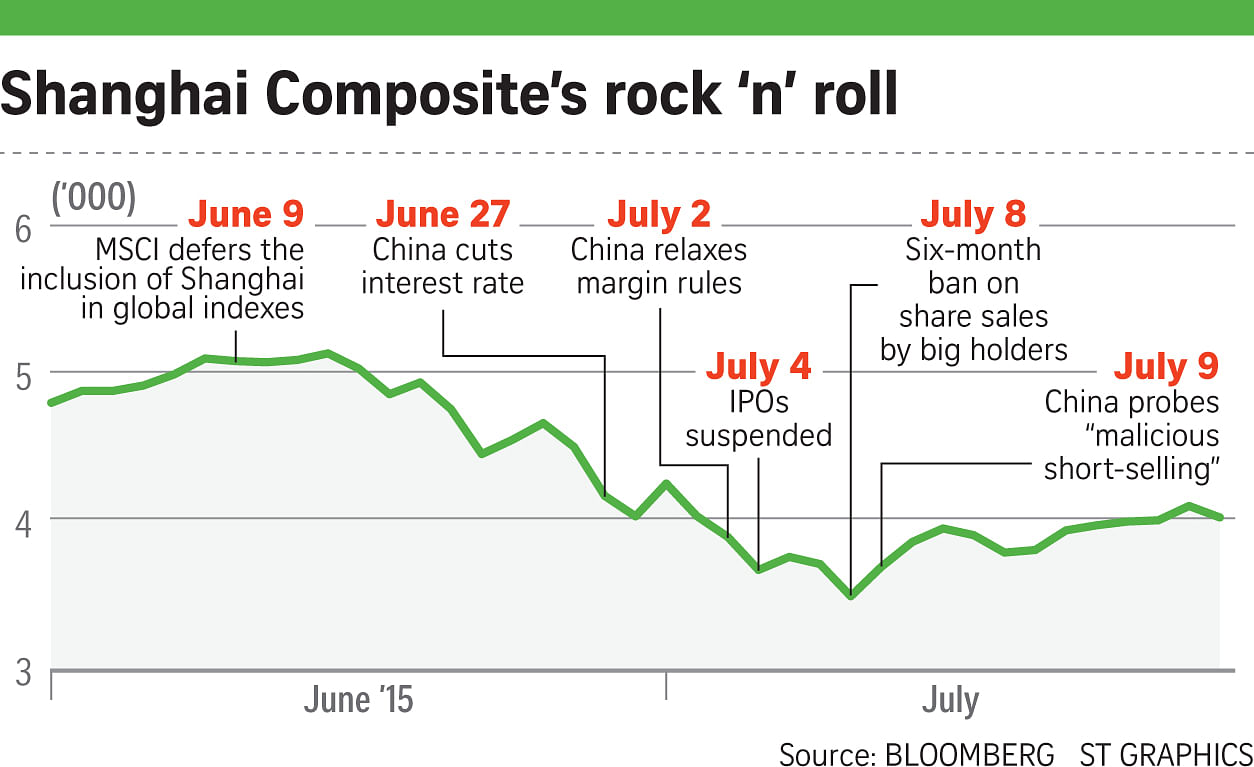

The Shanghai stock market had peaked at 5,166 points on June 12 just after prestigious index provider MSCI deferred its decision on including China shares in its global indexes. It then crashed, losing 32 per cent to a low of 3,507 by July 8 before enjoying a rebound to punch through 4,000-point level four days ago.

The rally followed a massive rescue effort by Beijing, which included an interest-rate cut by its central bank, suspension of new listings, giving insurers more freedom to buy stocks and a six-month ban on share sales by large investors.

More controversially, there was a state-funded buyout effort. As Shanghai went into a meltdown, the country's state-owned banks were said to have lent a combined 1.3 trillion yuan (US$209 billion or S$287 billion) to the China Securities Finance Corp, an arm of the Chinese stock market regulator, to give credit to mainland brokerages to finance share purchases.

Normally, such a spectacular stock market drama would have been headline news all over the world but the implosion of Chinese equities struggled to emerge from the business pages as the world's media trained their eyes on the unfolding debt crisis in Greece.

Yet the knock-on implications of the Chinese markets losing one-third of their value would have an impact far beyond Chinese shores if Beijing had folded its arms and done nothing to relieve the carnage.

Some market pundits bemoaned the fact that China's shock intervention may cause a delay in its shares getting included into indexes such as the MSCI and so access to the US$1 trillion of institutional money that invests in emerging markets.

But they failed to take into account the massive collateral damage that might have been inflicted on the world's financial markets if it had not done so.

Just to give a few examples. Some observers suggested that the fallout from China could have been contained as its stock markets were mostly off-limits to foreigners.

But as Shanghai dived, short sellers encircled Hong Kong, where many mainland firms have dual listings. The resulting sell-off caused the Hang Seng to fall by almost 2,000 points or 8.6 per cent - its biggest intra-day drop since the 2008 global financial crisis.

The carnage spread to the rest of Asia, causing the Straits Times Index to plummet 56 points, or 1.7 per cent - its biggest one-day drop this year.

Another casualty was the commodities market, where iron ore prices plummeted 11 per cent in a single day and copper fell to its lowest levels in six years as Chinese funds were forced to liquidate positions to plug their losses in the equities market.

Even gold was purportedly hurt by the China market crash. Its price crashed below US$1,100 an ounce, after US$1.7 billion of the precious stuff was dumped on the Shanghai market in a matter of minutes just after opening bell earlier this week.

With over US$3 trillion in value wiped out in the Shanghai/ Shenzhen stock markets in weeks, Beijing had no choice but to act, given the propensity for chaos as Chinese investors beat a retreat and licked their wounds.

Still, with a bit of luck, the bursting stock bubble in Shanghai and Shenzhen will be seen as another rite of passage to becoming a developed market. New York's rise to the top last century had, after all, been punctuated by similar manias and panics that culminated in the stock market collapse of 1929.

Despite the froth in segments of the China market, such as technological start-ups, Chinese blue chips were trading at price multiples of around 20 last month when prices peaked. This was not much higher than comparable valuations in the United States and Europe.

What essentially happened was a liquidity crisis triggered by a host of factors. The run-up was largely fuelled by margin financing, or buying of shares using borrowed money. Many of China's 90 million-plus investors are also uneducated, inexperienced and new to shares. Their only dream was to make a fast buck with as little effort as possible.

But while margin financing accelerates gains on the way up, the losses can snowball on the way down as markets tumble. This caused margin down payments to be wiped out and forced the investors to sell their shares.

The buoyant initial public offering (IPO) market exacerbated the liquidity crisis. Thanks to Beijing's policy of pricing IPOs attractively, new share sales mean almost guaranteed profit for investors and this caused huge sums to be sucked out of the market as investors chased listings.

Just before the crash late last month, the IPO fever was so intense that one offering - Guotai Junan Securities - locked up a staggering 2.35 trillion yuan in funds.

And as the rout accelerated, liquidity dried up further, as 1,300 mainland companies, or half of the firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, suspended trading of their shares to combat the indiscriminate selling that accompanied the meltdown.

This caused traders to resort to selling their China blue chips as they were unable to liquidate their holdings in the suspended counters to fund their margin calls - a move which added further pressure to widely watched indexes such as the FTSE China A50.

This explains the extraordinary actions taken by the Chinese government to douse the panic in the Shanghai/Shenzhen stock markets.

Citi Investment Research data showed that the week when the Shanghai market hit rock bottom, institutional investors poured US$4.9 billion into index funds tracking China equities. Last week, US$5.3 billion was taken out of China funds. This suggested that some of them might have cashed out their gains.

Given the volatile nature of the mainland market, more of such trading opportunities may arise. Fortune favours those who stay fleet-footed.