For retail investors, the key consideration for investing in a real estate investment trust (Reit) is the mouth-watering dividend yield it offers, as compared with the paltry interest they can get from bank savings accounts.

Yet, apart from the appetising dividends, many Reit investors remain ignorant of what they are getting into, other than the fact that Reits derive income from a business that specialises in owning estate assets such as shopping malls, offices, industrial buildings, warehouses or even hospitals.

The Reit sector is one of the Singapore Exchange's biggest success stories with 34 listings worth a total of $67 billion - Asia's second-largest Reit market after Japan.

Reits are "closed end" funds which operate in a manner similar to unit trusts. They currently offer dividend yields ranging from 5 per cent to 8 per cent. Funds raised by a Reit are used to buy a pool of properties which are then leased out to produce rental income that is later distributed to investors as dividends.

To manage the properties, a Reit will appoint a manager - usually the party which sponsored its listing. For the sponsor, the big attraction is the management fee paid to it as the Reit manager.

It is in the investor's clear interests to find out how the management fee is structured, as a hefty management fee may eat into the income produced by the Reit and result in investors getting a lower payout.

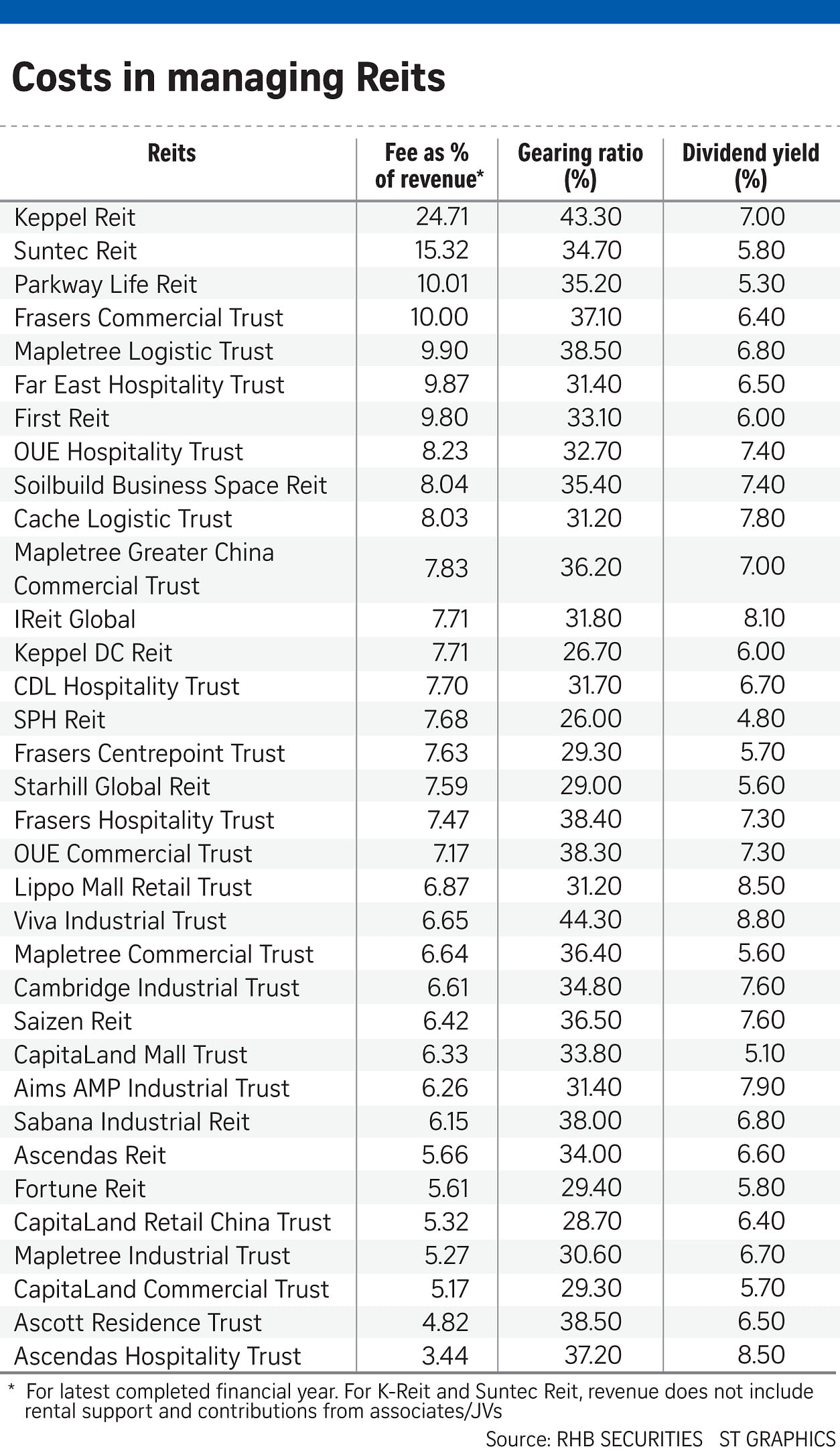

Data from RHB Securities shows fees charged by most Reit managers vary from 5 to 10 per cent of a Reit's revenues. But there are one or two exceptions where the fee can be as much as 24 per cent of revenues, boosted by income such as acquisition/divestment fees.

A Reit manager earns a fee from managing the properties in a Reit. This is made up of a base fee that is calculated based on a fixed percentage of the value of the properties in the Reit as well as a performance fee pegged to certain metrics such as the Reit's gross revenue, net property income or the dividend it pays out to investors.

It also gets a fee when it makes an acquisition. This typically works out to 1 per cent of the property's purchase price. When it sells a property, it also gets a fee which works out to between 0.5 per cent and 1 per cent of the sale consideration.

That raises a concern. As shopping malls, offices and industrial buildings now cost tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars, it may be lucrative for a Reit manager to constantly buy or sell the property portfolio under its care in order to earn more acquisition and divestment fees.

There is a further worry: Some Reit managers may have pegged their performance fee to the gross revenue or net property income earned by a Reit. As such, there may be an incentive for them to acquire more properties to grow the Reit's income in order to earn a higher fee. Extremely low interest rates also make cheap financing available to finance such purchases.

The only stumbling block to this fee gravy train is that a Reit's borrowings cannot exceed 35 per cent of its total assets, unless it has a good credit rating from a debt rating agency, in which case it can jack up its borrowings to 60 per cent of its total assets.

Against this backdrop, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) came up with proposals in October last year to improve the corporate governance of Reits and ensure that fees paid to Reit managers are aligned with the interests of investors. Its sweetener was a proposed increase in a Reit's borrowing limit from 35 per cent to 45 per cent of its total assets without the need for a credit rating.

But MAS noted the concerns expressed by some commentators that "the fee structure adopted by some Reits could incentivise the Reit managers to grow the Reits' assets rather than to focus on maximising returns for unit holders".

Hence, it wanted a Reit manager's performance fee to be linked to parameters such as the net asset value per unit in a Reit or the dividend paid out to investors. It also singled out specifically that the performance fee paid to a Reit manager should not be linked to a Reit's gross revenue.

On the issue of acquisition/divest-ment fees, which typically range between 0.5 per cent and 1 per cent of a property transaction, it wanted Reit managers to charge only on a "cost recovery" basis.

This is because it felt that "pegging the acquisition fee to the size of the transaction could result in Reit managers being paid a fee which is not commensurate with the amount of efforts expended or the cost incurred, particularly if the valuation of the transacted property is large".

As a Reit manager is already compensated through management and performance fees, there may also not be a strong basis for it to get a separate "incentive" fee when the Reit makes an acquisition or divestment, it added.

Furthermore, a Reit may be acquiring a property from its sponsor. In such cases, the scope of work performed by a Reit manager is likely to be more limited and administrative in nature, and this again raises the question as to why it needs to be paid a fee based on the size of the transaction.

Considering the strong language used in its consultation paper, it may be a tad surprising that the MAS has now watered down its proposals on the Reit manager's fee structure, even though it is pressing ahead to allow Reits to increase their debt leverage ratio to 45 per cent of total assets.

Rather than try to prescribe the type of fees that a Reit manager may be allowed to charge, the MAS had opted for a disclosure approach, asking only that the performance fee structure which a Reit manager adopts should be aligned with investors' long-term interests.

It wants disclosures on the various types of fees which a Reit manager charges to be "reasonable, informative and meaningful so that unit holders are provided with details of how the various types of fees co-exist and serve their purposes".

It also decided not to press ahead with the proposal to get Reit managers to charge a fee on a "cost-recovery basis" for any acquisitions or divestments made by a Reit.

This is said to be in view of the practical difficulties in implementing such an approach such as determining the time costs, the scope of work which a Reit manager has to undertake in doing such a transaction and getting the Reit trustee to sign off the payments to be made.

Will such an approach work?

Predictably, the climbdown by MAS on the fee structure was greeted by cheers from Reit managers.

But retail investors such as Mr Geoffrey Kung have expressed concern that allowing Reit managers to set their fee structure while giving them leeway to borrow more will work only to the detriment of Reit unit holders.

"While there are conditions which govern additional flexibilities for the Reit managers, these are conditions which the managers have sought for," he wrote.

With some annual reports now half the size of the Yellow Pages, the question arises as to whether investors will bother to plough through them at all to look up the salient information on a manager's performance fee and make a comparison.

Questions about the size of fees charged by Reit managers for property transactions remain.

Is it, for instance, reasonable for Reit managers to charge a 0.5 per cent to 1 per cent fee on a property which a Reit acquires from its sponsor since, as the MAS pointed out earlier, the scope of their work is likely to be more administrative in nature? In such cases, should they be allowed to cite "industry practice" to justify the fee they collect?

Some market pundits point out that even though MAS has opted for the disclosure route, it can follow up by suggesting some "best practices" guidelines for Reit managers that are aligned with the proposals which it made last October.

To ensure that the caveat emptor approach works, it may be useful for MAS to have a website which compiles the different fees charged by Reit managers in order to give investors a handle on what they are paying for.

Such a move would enable investors to reward Reit managers which prudently manage their Reit assets while avoiding those which may be churning their portfolios to earn a higher fee.

Sure, Reit managers need to be given incentives to look for good assets to invest in. But investors have to bear the consequences if anything goes wrong. Details of a Reit manager's mouth-watering fees should not be buried in the fine print.