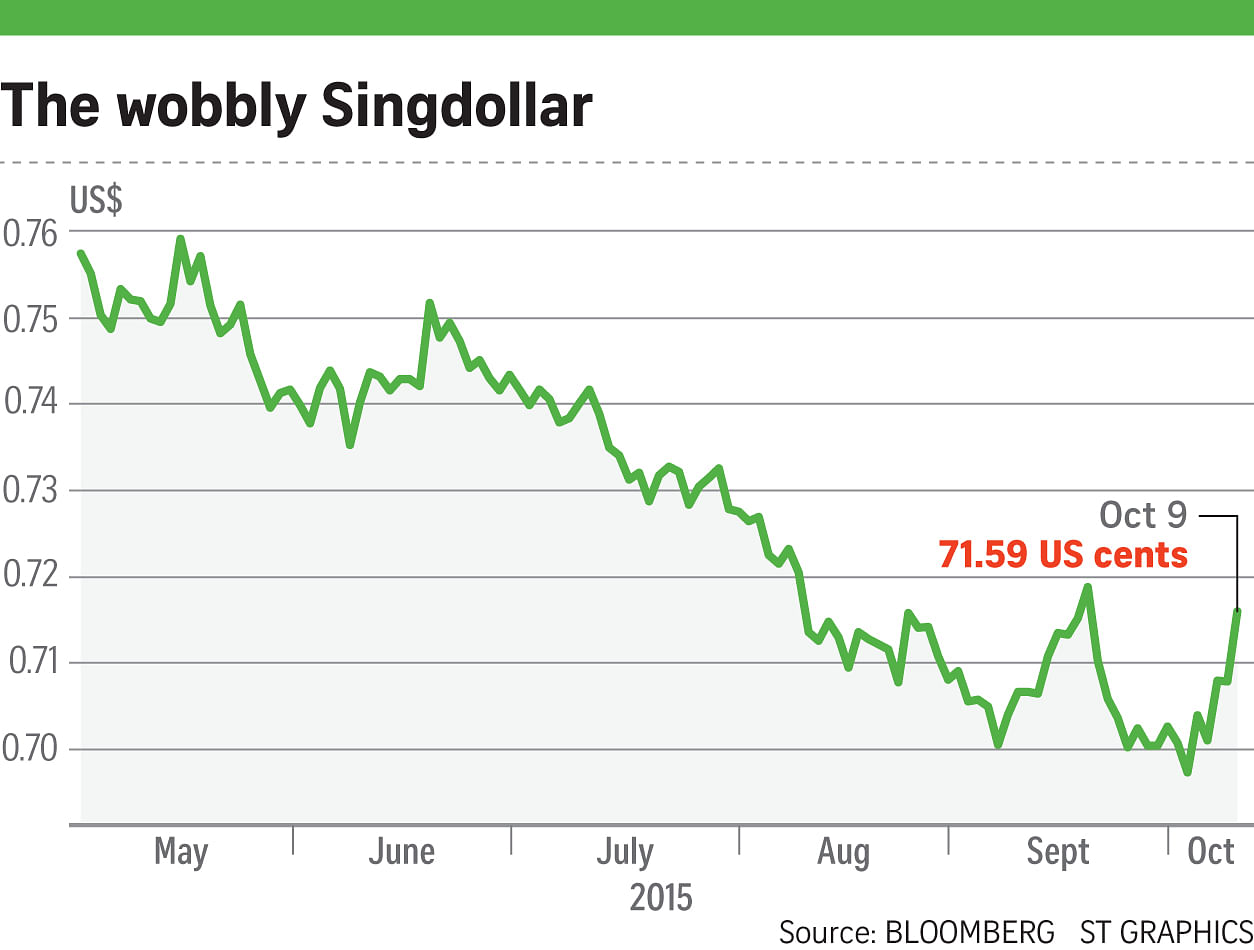

The shifting fortunes of the Singapore dollar tell an interesting story.

As recently as two years ago, market strategists were calling a "buy" on the Singdollar as investors pulled their money from other markets to park it here, prompted by fears including the euro zone debt crisis.

Now the tune seems to have changed completely. The Singdollar has become "everyone's favourite currency to short in Asia", as Citigroup strategist Siddharth Mathur puts it.

Some banks are even willing to offer higher than Sibor - the interest rate at which banks lend to each other - to try and lure their well-heeled clients to continue to park their Singdollar funds with them.

United Overseas Bank, for example, offers a step-up interest rate of 1.68 per cent until January for its "high yield" account - a savings-cum-cheque book account - for fresh funds of above $200,000.

This is well above the sub-1 per cent interest that Singdollar depositors have been used to getting since the global financial crisis six years ago, when the US central bank's aggressive efforts to pump liquidity into the ailing economy caused rates to plummet across the globe.

Yet, despite their efforts, some of their clients may not take the bait. Keeping cash in Singdollars may seem like an alluring option as interest rates start creeping up, but the high-net-worth clients that banks are pursuing may be more interested in storing US dollars than Singdollars.

This is because the capital gains they may enjoy from the greenback more than offset the negligible returns in holding, say, three-month US government bonds, whose yields have fallen to zero recently.

Since January, the US dollar has gained as much as 9 per cent against the Singdollar and it is likely to strengthen even more.

The challenges confronting the Singdollar mirror the wider struggle faced by leading emerging economies such as China and Brazil in trying to stem the outflow of funds from their markets.

The Institute of International Finance recently estimated that foreign investor inflows into emerging markets will likely fall to just US$548 billion (S$764 billion) this year from just over US$1 trillion last year. More tellingly, it expects a net capital outflow of US$540 billion for this year - the first time this would have been seen since 1988.

In a nutshell, that means resident investors will be taking a staggering US$1 trillion out of emerging markets this year.

No doubt, one reason for the big fund outflow would be repayment of foreign currency loans, especially by China-based companies as the yuan weakens against other major currencies.

But part of the outflow is also due to investors liquidating an estimated US$40 billion worth of equities and stocks in the third quarter. This marks the biggest sell-off of emerging market stocks since the fourth quarter of 2008, which coincided with the peak of the global financial crisis.

A Citi Investment Research report shows that in the past 12 weeks, fund managers were relentlessly cutting their exposure to emerging market stocks. Not a single week had gone by without a sell-off in Asia.

The sell-off, which started in August, had initially been triggered by China's sudden devaluation of its currency and subsequent concerns over its economy.

It was then aggravated by uncertainty from the US central bank's decision to keep interest rates at near zero levels despite widespread anticipation that it would raise rates last month.

This was followed by a global relief rally in shares following weaker-than-expected September job data in the US, which raised hopes that the Federal Reserve would postpone any move to hike interest rates till next year at the earliest. A rebound in crude oil prices also helped to stoke the buying spree.

Some experts believe the worst is over for emerging market equities.

Fund management firm Columbia Threadneedlereckons that opportunities abound.

It noted in a recent report that investors should not lose sight of the "structural growth drivers" that made emerging markets an attractive investment proposition.

"At the centre of these is the rapidly expanding middle class, eager to enjoy a higher standard of living and consume a wider range of goods and services. For this reason, we believe that areas such as healthcare, e-commerce and modern food retail remain extremely attractive areas for investment," it wrote.

But the International Monetary Fund warns in its recent Global Financial Stability Report of a severe credit crunch that could be triggered by the heavy US$3 trillion debt burden shouldered by emerging market companies if interest borrowing costs escalate.

There are those who believe that companies in emerging markets can shrug off a US rate hike because much of their debts is made in local currencies. This is unlike the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis when debt-laden South-east Asian firms found themselves unable to service their US dollar loans as their local currencies plummeted against the greenback.

But the strong US dollar is already causing interest rates to rise in emerging markets, even without the Fed doing anything. This has caused borrowing costs to rise for emerging market companies, and the likelihood is that this trend will continue.

The worry is that businesses, which had taken rather more debts in the past five years but whose prospects are now dimmer, may go bust if they cannot service their loans. If that happens in large numbers, the problems may spread to the banks which lent them the money.

Britain's Financial Times noted that in the past, investors' attention had been seized by quantitative easing (QE), the efforts from the US Fed to pump trillions of dollars into the financial system.

But little attention was paid to the enormous sums that were recycled into emerging markets as a result of QE. Now that QE has ended and the Fed is poised to hike rates again, the question is what happens to the money sloshing around in emerging markets.

"Some policymakers hope any shock could be contained by more money creation on the part of Western central banks - a bit more QE might calm markets, or so the argument goes... But the emerging market bubble may be so big that it is far from clear that central banks could plug the gap," the FT added.

In other words, the torrent of fund outflow from emerging markets may be flagging a possible credit crunch that may not be resolved simply by the Fed staying its hand on any interest rate hike.

Besides watching the Fed, we should keep an eye on the funds fast draining out of emerging markets. They do not tell a pretty story.