Mr Christian Jeune was a 15-year-old schoolboy when he first heard of the Cannes Film Festival.

Curious, he skipped school one day and took a train from his home in Toulon - a city in Southern France - to the seaside resort town.

At the Palais de Festival, the hub of the festival, he saw a woman distributing tickets to film professionals and managed to wrangle one for himself.

He found himself at the screening of A Special Day, a 1977 Italian film by Ettore Scola. Starring Sophia Loren and Marcello, it is about a woman who strikes up a friendship with her mysterious neighbour the day Adolf Hitler visits Benito Mussolini.

The grand theatre where the film was screened was like nothing he had seen before. The film captivated him too.

"It was a big shock," says Mr Jeune, now 55. "The room, the emotions, the excitement. I remember telling myself, This is where I want to be. This is where I belong."

Single-mindedly, he worked towards realising that ambition, starting with low-level jobs around the world's most famous and prestigious film festival.

Today, Mr Jeune is director of the festival's film office as well as deputy to Cannes' chief Thierry Fremaux.

Lauded as Cannes' behind-the-scenes hero, he traverses the globe to scout for movies, and plays a key role in the pre-selection and selection process.

On first-name terms with the who's who of the film industry, he has sat on countless film juries around the world, and translated scores of films from English into French.

Soft-spoken but with a droll sense of humour, he is the youngest of four sons of a mechanic working on an aircraft carrier, and a housewife.

His early years were spent in a council flat where the residents were mostly shipyard workers.

A self-starter, he excelled in his studies, mathematics in particular.

"I never enjoyed it and was bored by it but I was super good at it. I found other subjects such as literature, history and geography more intellectually exciting. For instance, I struggled with philosophy but I loved it," says Mr Jeune, who was in Singapore last month to attend the Singapore International Film Festival.

In his early teens, he was put in a class with other maths whizzes. "I didn't like the boys and girls there; I felt that I didn't belong and I didn't want to end up like them," he says.

After six months, he asked to speak to the class and dropped a bombshell. "I said, 'Today is the last day of my life that I would deal with mathematics'," he recalls with a grin.

Alarmed, his school asked to see his father, on more than one occasion. After getting Mr Jeune's assurance that it was a decision he would not regret, his father told the principal: "He doesn't want to do maths anymore, so leave him alone. Otherwise, I'm going to be very angry."

The episode, he says, was a turning point in his life.

"I have several nephews who always tell me they are not sure what they want to do with their lives. I tell them that there are certain things you have to be strong about, and which you should not compromise.

"I was lucky because I had parents who were supportive. They didn't put pressure on me, and told me the most important thing was that I was happy. That's the most important thing parents can tell you in life."

At that stage, Mr Jeune had not quite figured out what he wanted to do in life.

"The only thing I knew was that I was going to live in the city and that I would travel," he says.

After completing high school, he attended university in Nice where he studied English, Greek and Spanish. As part of his degree course, he spent a year in London where he worked as a French-language teaching assistant.

A diplomatic career seemed appealing, so he decided to enrol in a two-year preparatory course at the School Of Oriental Languages in Paris. But a two-year stint teaching French in Bangladesh made him change his mind.

"In those days, national service was compulsory and if you were a graduate, you could choose to do two years abroad as a civilian, instead of one year as a soldier in garrison," says Mr Jeune, who opted to be a French teacher at a university as well as the Alliance Francaise in Dhaka.

There were then about 80 people in the French expatriate community in Dhaka.

"It scared me a little and I'm generalising a little but these people were always talking about the country they were in before, and the country they were going to be posted to next. I was thinking to myself, 'What about the country you are in now?'

"I was fascinated by international relations and what I was studying but I lost my desire to be a diplomat. I finished my preparatory course but I didn't sit the exam although I'm sure I would have passed. It was like my episode with maths, it was the second time I said 'no'," he says with a grin.

If he did not lose sleep over this, it was because Cannes and celluloid had already wormed their way into his heart.

After that first trip at 15, he made the yearly pilgrimage to the festival, sometimes taking his friends with him.

The array of films screened made him dizzy. He watched as much as he could, and read up as much as he could. "When I discovered the Japanese masters like (Yasujiro) Ozu, (and Akira) Kurosawa, I was shocked. Their films were talking to me in a very strange and intimate way."

He ponders when asked how he defines a good film. "I like it when the feeling you get from watching a film is almost carnal, when the film sticks to your skin, and you feel it with your body."

Alas, in 1981, the festival - which will celebrate its 70th anniversary this May - introduced an accreditation system, effectively cutting Mr Jeune's access to movies.

"I felt as though something was stolen from me, it was so unfair," he says. The only solution, he decided, was to join them.

Just like the letters he used to write to Santa Claus as a child, he sent one to the festival. It contained no resume; he did not even write the address or the zip code on the envelope.

He says: "I just wrote, 'My name is Christian and I want to work with you.'"

Amazingly, he received a reply not long after. A woman interviewed him and offered him a job as a driver.

"I said, 'But how am I going to watch movies?' And she said, 'Young man, you're interviewing for a job.' And I said, 'Yeah, but I'm looking for a job at a film festival, not a garage.'"

Exasperated and amused at the same time, she hired him to distribute leaflets for the festival's press office.

"She said, 'You finish at 5pm. What you do after that, I don't want to know.'"

For several years after that, he worked at the festival each year.

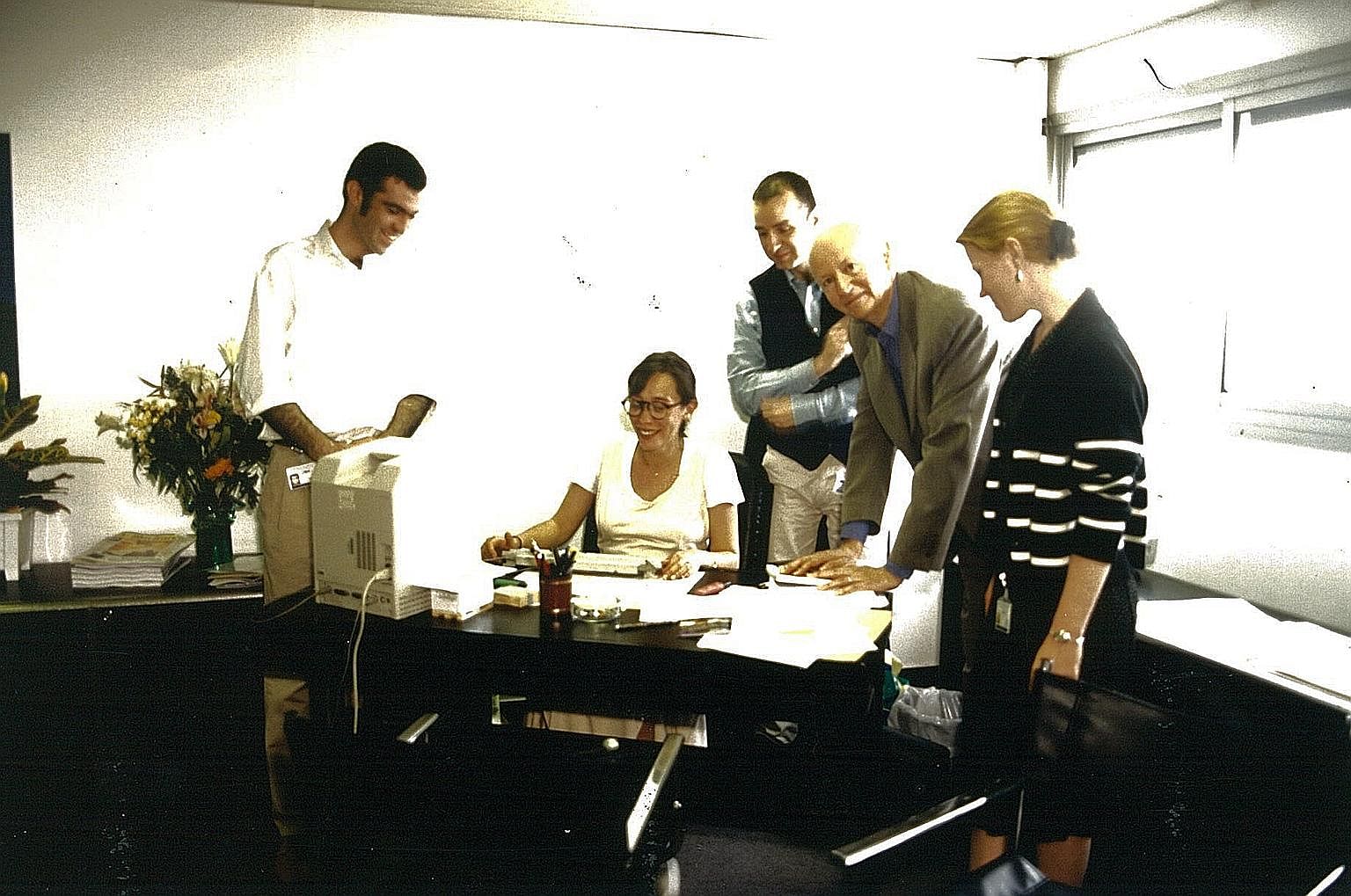

When he decided not to sit the diplomatic exams in 1990, Mr Gilles Jacob - the festival's former artistic director - offered him a part-time position in the film department.

Six months later, the position for head of the film department became vacant.

"Gilles offered it to me but I turned him down. He was so shocked. He said, 'This is a permanent position. You can't say 'no.' But I said 'no'," says Mr Jeune.

"I had enough to survive. The freedom and the time to do other things such as travelling and translating were more important to me. I've never liked being tied down."

The permanent position was offered to him again not long after. This time, he accepted, on the condition that he worked only six months a year. This was extended to eight months a couple of years later.

He is, by his own admission, an oddball.

"I have no attachment to things. People and friends, yes, things, no. When I was a kid, I'd give away clothes and toys all the time. My mother would scold me because it was not easy for her; she had four boys to raise.

"But a few years ago, she told me, 'It was so difficult as a mother to scold you as a kid for giving away your things. Deep in my heart, I was so happy that you were so generous but I could not afford to tell you that it was the right thing to do'," he says.

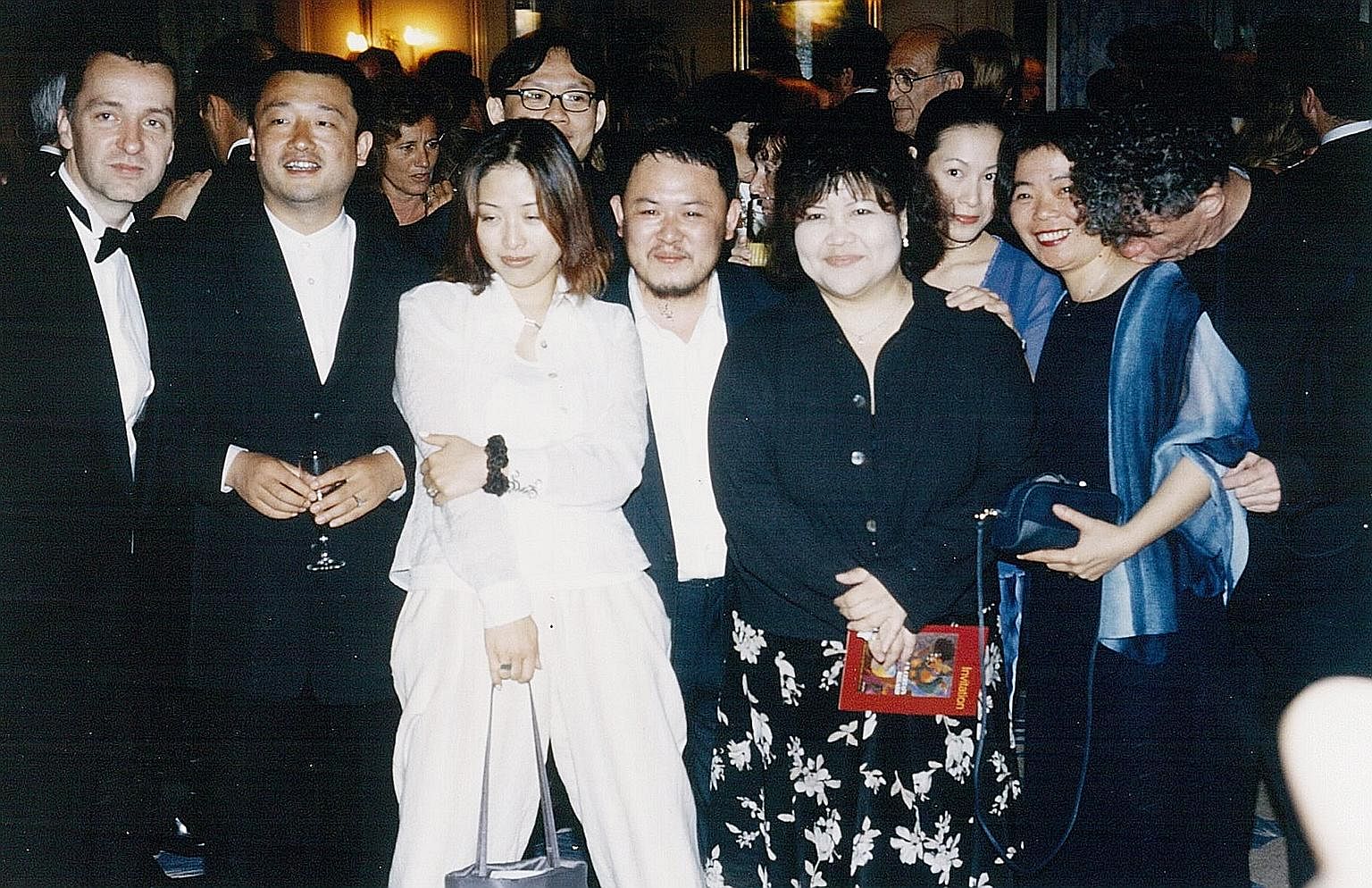

From the late 1990s, he started travelling to scout for movies.

Asia, in particular, was a hot destination because its film-makers were beginning to make their presence felt on the world stage.

In 1997, he was on the road for three months travelling to countries such as China, Korea, Thailand, Australia and Argentina to build a network of new and emerging film talents and professionals.

He remembers meeting the likes of Tian Zhuang Zhuang and Wang Xiaoshuai, key members of China's fifth and sixth generations of film-makers, under cloak and dagger conditions.

Many works by these film-makers - Tian's The Blue Kite and Wang's The Days - were banned by the Chinese authorities then for being politically controversial.

"We had to change cars just to see a film and I thought it was all a bit too much because I was not James Bond," he says with a laugh.

But he soon realised it was not paranoia on the part of the film-makers.

"I stayed in China for 10 days, and one day, the hotel receptionist rang me and told me my lunch appointments were here. I told her I had no appointments but she said, 'You'd better come down now'."

He did, and was met by two men and a woman in dark suits and dark glasses who knew what he had been up to and who he had seen.

"They also invited me to watch films produced by the Chinese Film Bureau," he says.

There were many other memorable experiences, such as visiting the spectacular set of Ang Lee's blockbuster martial arts movie Crouching Tiger And Hidden Dragon in China.

Besides pre-selecting movies, Mr Jeune, who became the festival's deputy director about 10 years ago, is now a key member of the official selection committee.

He also has a firm which does film translation and subtitling from English into French. His credits include the James Bond blockbuster Skyfall, and the psychological drama Stoker directed by Korean film-maker Park Chan Wook and starring Nicole Kidman.

Not surprisingly, he has been asked, at various points in his life, to produce, write or direct movies.

His answer? "No," he says.

"I've never done it, and I never will, not at my age. I'm a professional spectator. I don't want to get involved in the process, I just want to watch the finished product.

"And I still get very excited each time I sit down to watch a film."