COX’S BAZAR - The family’s possessions are few and all their clothes are strung across a short nylon line in the flimsy structure of bamboo and tarpaulin that serves as home.

But when Mohd Abdul Hamid starts to speak of life in the Rohingya camps, his wife Madam Salama Khatoon goes to a corner of the hut and fishes out two articles of clothing that she keeps apart from the rest. One is pink, the other blue and they belonged to the couple’s daughter, Unaishya, who died in this camp where the family live with their three remaining children.

The couple stare in silence at the only items they can remember their daughter by.

There is no trace, on the other hand, of their oldest child Kamal Sadiq, 10, who died when the family crossed two rivers to flee the violence in Myanmar for the safety of Bangladesh across the border. They abandoned his body in the hills.

Unaishya reached Kutupalong in Cox’s Bazar safely. Mr Abdul Hamid, 33, says that she was three years old, and pretty.

“We had to sleep in the open while my wife and I assembled this hut. Sometimes there was enough to eat and sometimes there was not. Sometimes it was wet. Unaishya caught pneumonia and we buried her about 2km from here.

“We thanked Allah when we got here because we thought we were safe. But now I have lost one child in Myanmar and one in Bangladesh. The rest of us have nowhere to go.”

For if he and 919,000 other Rohingya refugees thought they had escaped the death penalty in Myanmar by fleeing from their home state of Rakhine to Bangladesh, they now find themselves staring at a life sentence – squashed in cell-like units, ill, hungry and stuck with endless time on their hands.

Home now is a place called Kutupalong megacamp in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district that till last year was known for its hills and forests and 120km of unbroken beach.

Today, a stretch of hills has been hacked down for the megacamp complex. About 626,000 people are squeezed into a 12 sq km area, with 6,000 overflowing latrines, the smoke from firewood and that morning’s rain creating a warm, wet stink. The remaining Rohingya – whom everyone calls refugees while speaking, but never in writing – are placed in similarly squalid smaller camps.

For a people who worked on farms and fished in rivers, it is the feeling of being boxed in that galls the most. The huts touch each other in an unending labyrinth. “I can hear my neighbours fight. I can hear their children throw up. And I can’t leave the camp because I am not allowed to,” says Mr Abdul Rahim, 61.

Someone his age is rare in the camps where only 3.3 per cent of the people are above 60.

NO PERMANENT HOMES, NO WORK, NO CASH

The Bangladesh authorities laid down the camp rules early: the Rohingya would not be given cash or allowed to work, except for odd-jobs in camps; they could be given relief only in kind; they could not put up any permanent structures in camps.

“They are afraid that if we are allowed to build proper homes, we will settle here and never go back,” says Mr Mohibullah, chairman of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights – a grouping that has become the main voice of the displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh. But as time passes, these rules are taking their toll.

At 11.30am in the Balukhali camp, no one in Mr Nurul Amin’s family of seven has had a bite to eat, except his daughter Nur Fatimah, eight, who was given a biscuit at a learning centre she attends.

“They give us rations of rice, lentils and oil every fortnight,” says Mr Amin, 32. “By the 12th day we start running out of food.”

It has been 11 months since he ate meat or vegetables. That was at his village in Myanmar the day before the army came gunning for them on Aug 25. He has not had a cup of tea since then, nor a slice of bread. Every meal is rice and lentil cooked on a clay stove with brackish water over damp firewood by his wife Anwar Jahan, until the rations run out.

In theory, they could buy stale vegetables or cigarettes from Myanmar from one of the little stalls that have sprung up at the mouth of the camps.

Till earlier this year, camp residents used to earn some money by helping build latrines and bridges in the camp. Mr Amin found work for a total of six days over 11 months, earning 400 takas each time, or a total of $40.

Now the army has taken over most of the construction work to speed things up and, ironically, this has cost the Rohingya a source of income. Mr Amin has found no work since June. “I have exactly zero takas with me,” he says.

Mr Mohammed Abdus Salam, head of the Humanitarian Crisis Management Programme of BRAC, a key NGO offering relief agency, says this policy – which assumed that the Rohingya would be in Bangladesh for only a short time – must change.

“We have to give them cash for work. How else do you expect them to survive in the long run?” he says. His organisation is helping to build shelters, provide water and teach children. NGOs as a whole are fighting heroically to help, but they, too, are starved for funds and have raised only US$260 million(S$355 million) of the US$950 million that they need.

Meanwhile, people need cash to get by. Some are encashing their food vouchers while others are selling the relief material that they get to buy things they need from the stalls. “Already the food is not enough for them,” says Dr Anik Sanjoy at a health centre in Kutupalong. “When they sell some of it to buy other things, they eat even less.”

Almost 13,500 children below the age of five have already been treated for severe malnutrition. The camp is sick, with worms coming out of children’s mouths, skin problems breaking out amid poor hygiene and contagious diseases multiplying.

“When 12 people sleep in a room, they pass the germs to each other,” says Dr Sanjoy. Hunger among adults is growing fast, he says. “When there is a shortage of food, the parents go hungry so that their children can eat.”

It is normal for Mr Amin and his wife to get by on a single meal a day.

He wakes up at what he guesses is around 5.30am in time for the first namaaz (prayer). After that, it is a question of wondering how to spend the day. “When it gets too muggy inside, I go out. When it rains outside, I come in. Sometimes I take a walk to look for firewood, but today there is nothing to cook. Then I lie down inside for many hours, but sleep doesn’t come.”

Having taken them in, Bangladesh cannot very well send them back to their deaths, but it refuses to treat them as refugees with rights.

With mounting evidence that the Myanmar army plotted the events of Aug 25, 2017, precisely to eject the Rohingya Muslim minority from the country – it treats them as stateless– it is not reopening its doors to them.

Mohd Eliyas, a rare Rohingya graduate, says the overwhelming feeling in the camps is of mounting depression and helplessness.

“We have mouths but cannot speak,” he says. “We have legs but cannot walk. No mouth power, no money power. Only eye power and ear power.” Less eloquently, but more wearily, Mr Amin says he wants to return to Myanmar, even though it is where he dodged death.

He and his family of seven cannot continue to live like this, he says. “There is no future here. My children cannot study. The camp is like prison and I cannot leave it or find work. My wife has no rice to cook. Maybe the world will make it possible for us to go back. Otherwise, I will just spend every day like this and die here.”

When 60,000 teenage girls hide in fear

They swelter inside – rape, violence an ever-present danger. Little water, few toilets are another ordeal, resulting in an overwhelming stench.

Whether it is on the treacherous slopes of Kutupalong’s camps, in the makeshift learning centres in nearby Balukhali or on the winding paths of Nayapara, there is one face that you never see: the face of a teenage girl.

It is as if she has been airbrushed from the scenery.

Between them, the camps hold more than 60,000 girls between the ages of 12 and 17. But even in this cramped, makeshift township, where shanties lean on each other and there is no place to hide, these young females have been banished from public view.

When non-governmental organisations tried to find out why no teenage girl attends a learning centre, they were told: “A girl’s modesty is more important than education.”

In fact, of the 117,000 young people between the ages of 15 and 24, only 2,000 attend any sort of training or educational programme and almost none of them is female.

The girls stay locked indoors, in the shanties, where the blazing sun and the clay ovens push temperatures into the 40s. “I sit under the tarpaulin and sweat,” said Rukhmah, 17. “I want to step out but there are so many strangers.”

The fear of strangers is not unfounded. Of the 1,922 locations that the International Organisation of Migration surveyed across all Rohingya camp settlements in Bangladesh, it found that women had been sexually assaulted at bathing points or latrines in 70 per cent of them. In more than 1,800 of these locations, the toilets were not segregated by gender.

That, and the shortage of water, kept these young women from bathing for days on end during the summer. “Our women smell so bad that sometimes it is hard for us stay indoors with them,” said Mohd Fazal, a father of six.

The bad odours are outdoors, too, as the latrines overflow. In one block at Nayapara, there are 10 common toilets for 3,072 camp residents. Or one for every 300.

“If I want to use the toilet in the morning, I have to stand for so long that my knees hurt,” said Malika, 32.

And if she and other women wait till night, the camp is plunged into darkness, without a single lamp to light it up. That is when most attacks take place.

Some of the women feel particularly vulnerable as there are more than 6,000 widows of last year’s violence in the camps. Of every 100 households there, 10 have women who were raped by the army in Myanmar last year. Women sit and talk about rape even to strangers, but the pain has not been numbed.

Madam Noor Beghum, 30, tells you matter-of-factly how she saw her husband hacked down and how several soldiers raped her that night. When she emerged from her unconsciousness next morning, she gathered her four children and escaped to Bangladesh. By now she has started to weep, though she is saying: “I got lucky. A family with seven children took us in. Even though their home is small, they share it with us. I feel safer staying with them.”

Her quarters are so tiny that she can touch the tarpaulin walls on either side just by stretching her arms. She and her children don’t venture out after dark. “Sometimes it is so hot at night that we can’t sleep,” she said. “And sometimes when I sleep I wake up screaming.”

Other women at the camps have also discovered a darker truth. Sometimes the enemy is not the stranger, but the man sleeping by your side.

NGOs have set up spaces that shelter women who are victims of domestic violence. As each tells her story, it becomes clear that it is essentially the same story.

Sadiah mumbles without opening her mouth much and the reason soon becomes clear. She is missing two front teeth. Her children, aged three and five, had started to cry as they were hungry, and “my husband smashed my head against the wall and broke my teeth,” she said. “Then he left me for another woman.”

Another woman, Fareeda, got beaten up because she complained to her children that her husband was having an affair with a woman from a neighbouring quarter. In turn, the woman who was having an affair got beaten up by her own husband.

WOMEN ARE EASY TARGETS

“These are small, squeezed spaces and everyone is frustrated,” said Mohd Eliyas, a community volunteer. “The women are easy targets. They get beaten up by their husband who are having an affair, and they also get beaten up if they have an affair themselves.”

Already, more than 19,000 women from the camps have received counselling in connection with violence, usually from the men in their family.

Dr Anik Sanjoy, a medical practitioner at the camp, said he never ceases to be amazed by how much the Rohingya women have endured in silence. “They have been raped, beaten up and seen their family members die. Still, they continue to care for their children. When the pregnant ones come to give birth, I see them get up and walk away with the baby just 15 minutes after delivery.”

Some 48,000 women are expected to give birth in the camps this year. The miracle of motherhood comes in many forms, but none, perhaps, as remarkable as in the case of Rukhiya.

The 25-year-old was fleeing Myanmar with her husband when she heard a sound on a hillside. Someone had abandoned an infant aged around two amid a clump of plants. “I picked her up and hugged her to my chest,” said Madam Rukhiya. “I didn’t have any children and this was a gift from God.” Now she pampers the child that she has named Arifa. She sells off her food vouchers to buy toys for the girl. “She is always asking me for things but I can’t afford to buy most of them,” she said.

But there is no tale of unalloyed joy in the camps. Some months after Madam Rukhiya found her daughter, her husband left her because she, herself, had not borne him a child.

The story behind the story

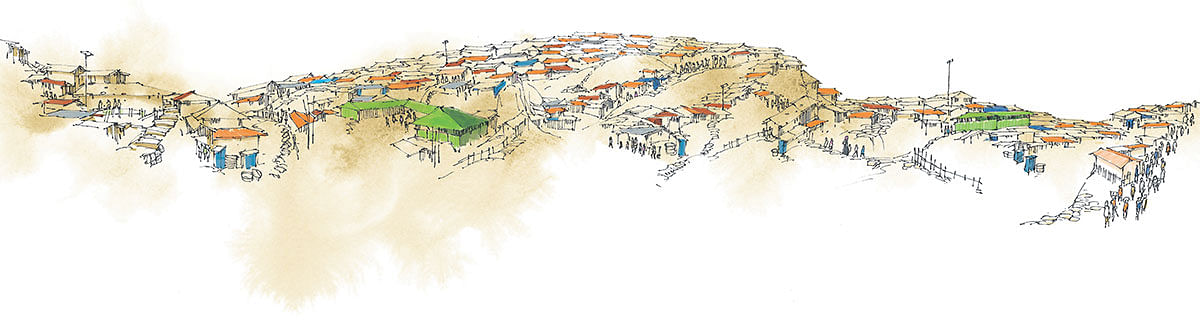

Tens of thousands of makeshift tents made of tarpaulin, rope and bamboo cover an area the size of Sengkang at 12 sq km. Crowded into this megacamp are more than 600,000 people who have fled rape and massacre in their homeland in Myanmar. Another 300,000 have been placed in other camps.

Planning the visit to the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh, The Straits Times decided to rope in art director Pradip Sikdar. Not only is he a brilliant artist whose perspective of the sprawling camps would give readers a sense of scale beyond the scope of any camera, we figured, but he also speaks fluent Bengali, the language of Bangladesh and, presumably, the Rohingya.

When we reached Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, on our way to Cox’s Bazar and met local journalists, this supposition went out the window.

The average Bengali cannot understand the Rohingya dialect, we were told by a reporter who had made several trips to the camps.

His other advice was more practical: Buy rain-proof shoes and gamchha, a local Bangladeshi cotton towel, to shield your head from the sun.

Some international journalist friends gave us contacts of local “fixers” who would translate for us and arrange to show us around the camps.

Fortunately, we met the editor of a Bengali newspaper who put us in touch with his stringer – a freelance journalist – at Cox’s Bazar.

This stringer did not speak English well, but he spoke the Rohingya dialect and Bengali. Pradip Sikdar spoke Bengali, but not the Rohingya dialect. Each question went through a three-step translation process. I would ask it in English, Pradip would translate that to Bengali and the stringer, in turn, conveyed the question to the Rohingya people in their dialect. The answer would come back through the same route.

TOURIST BEACH, TO CAMP OF DESPAIR

The drive from the hotel in Cox’s Bazar to the camps was a tale of two halves. It would start along a beautiful road called Marine Drive – a road that flanks the gorgeous, unbroken 120km Cox’s Bazar beach that is the longest in the world – before veering into the narrow path to Ukhiya, where some of the camps are based. There the car would slow to a crawl behind the vehicles transporting officials and volunteers on roads that were never made to bear so much traffic. Eventually, the 42km drive would take between 2 and 21/2 hours.

Though The Straits Times team had read about the camps and seen pictures beforehand, when we eventually drew up before Kutupalong camp for the first time, it shook the senses. The size, the smell – and the sorrow – got to us and we nearly threw up.

It had rained earlier that day and the mudpath kept dissolving beneath our feet. But the sun was beating down and etched a darker shade on our faces. We walked six or seven hours that day, stopping to talk to grim men and giggly children.

Speaking to rape victims was gut-wrenching. Each would start speaking in a composed manner, then tears would start to well until eventually they were sobbing and speaking at the same time. But each insisted on telling her tale, without shame. For there was nothing that they had done wrong.

Every morning during our five-day stay in Cox’s Bazar we’d leave the hotel at 9am after breakfast and make our way back around 9pm.

Most people spoke candidly. Some asked for money to speak and introduce us to others. US$100 (S$137) a day was the going rate, they said. We politely refused.

At one camp, the community leader – they are called majhees – arranged for us to speak to some people. There was no talk of money. We spoke to some women and children and to the majhee himself.

Barely had he finished speaking when a burly man barged in and started slamming the majhee’s face to the ground. “This majhee is making money off us,” he said. The majhee then used a phone to call his own men. We left.

Each evening we’d come home hungry, our backs hurting, complaining about traffic.

Then we would think of the widows we had met, the orphans still smiling, the victims of rape and hunger – and feel ashamed of ourselves.