NEW DELHI • Ed Dohring, a doctor from Arizona, had dreamt his whole life of reaching the top of Mount Everest. But when he summited a few days ago, he was shocked by what he saw.

Climbers were pushing and shoving to take selfies.

The flat part of the summit, which he estimated to be the size of two ping-pong tables, was packed with 15 or 20 people. To get up there, he had to wait hours in a line, chest to chest, on an icy, rocky ridge with a drop of several thousand feet.

He even had to step around the body of a woman who had just died.

"It was scary," he said by telephone from Kathmandu, Nepal, where he was resting in a hotel room. "It was like a zoo."

This has been one of the deadliest climbing seasons on Everest, with at least 10 deaths or people going missing. And at least some seem to have been avoidable.

The problem has not been avalanches, blizzards or high winds.

Veteran climbers and industry leaders blame the presence of too many people on the mountain, in general, and too many inexperienced climbers, in particular.

Fly-by-night adventure companies are taking up untrained climbers who pose a risk to everyone on the mountain.

And Nepal's government, hungry for every climbing dollar it can get, has issued more permits than Everest can safely handle, according to some experienced mountaineers.

Add to that Everest's inimitable appeal to a growing body of thrill-seekers the world over.

And the fact that Nepal, one of Asia's poorest nations and the site of most Everest climbs, has a long record of shoddy regulations, mismanagement and corruption.

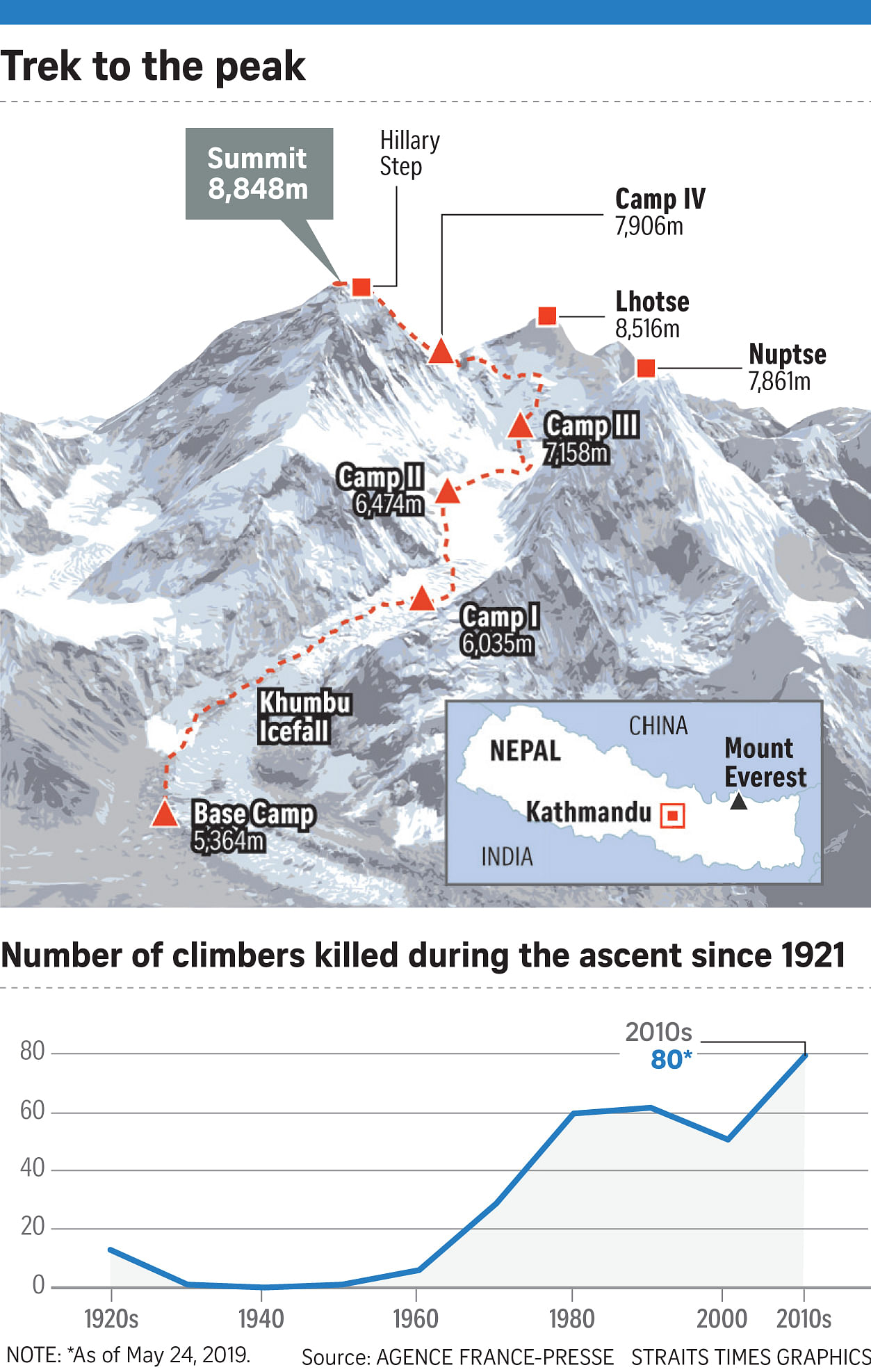

The result is a crowded, unruly scene at 8,800m. At that altitude, a delay of even an hour or two can mean life or death. The summit itself is 8,848m.

But Nepal's tourism authority said the deaths cannot be solely attributed to overcrowding on the mountain. The department's director-general, Mr Dandu Raj Ghimire, told the BBC that adverse weather conditions and other factors were also to blame for climbers dying or going missing on the peak. Mr Ghimire put the current death toll at eight.

He said that due to the short periods of fine weather, the number of people on the routes had been higher than expected.

Four Indians, an Australian, an American and a Nepalese were among those who have died or gone missing on the mountain. A local tour organiser said that one of the Indian climbers died of exhaustion after being "stuck in traffic for more than 12 hours".

Mr Ghimire offered "heartfelt condolences to those who've passed away and prayers to those who are still missing".

"Mountaineering in the Himalayas is in itself an adventurous, complex and sensitive issue requiring full awareness, yet tragic accidents are unavoidable," he told the BBC in an interview .

To reach the summit, climbers shed every pound of gear they can and take with them just enough canisters of compressed oxygen to make it to the top and back down. It is hard to think straight at that altitude, climbers say.

According to Sherpas and climbers, some of the deaths this year were caused when people were held up in the long lines on the last 300m or so of the climb, unable to get up and down fast enough to replenish their oxygen supply.

Others were simply not fit enough to be on the mountain in the first place. Some climbers did not even know how to put on a pair of crampons, the clip-on spikes that increase traction on ice, Sherpas said.

Nepal has no strict rules about who can climb Everest, and veteran climbers have said that is a recipe for disaster.

"You have to qualify to do the Ironman" triathlon, said prominent Everest chronicler and climber Alan Arnette. "You have to qualify to run the New York marathon. But you don't have to qualify to climb the highest mountain in the world? What's wrong with this picture?"

The last time 10 or more people died on Everest was in 2015, during an avalanche.

By some measures, the Everest machine has only gotten more out of control.

Last year, veteran climbers, insurance companies and news organisations exposed a far-reaching conspiracy among guides, helicopter companies and hospitals to bilk millions of dollars from insurers by evacuating trekkers with minor signs of altitude sickness.

Climbers complain of thefts and heaps of trash on the mountain.

And this year, government investigators have uncovered vast problems with the lifesaving oxygen systems used by many climbers.

Climbers said cylinders had exploded or had been found to be leaking or to have been improperly filled on a black market.

But despite complaints about safety lapses, Nepal this year issued a record number of permits, 381, as part of a bigger push to commercialise the mountain.

Climbers said the permit numbers have been going up steadily each year and that the traffic jams this year were heavier than ever.

"This is not going to improve," said Mr Lukas Furtenbach, a guide who relocated his climbers to the Chinese side of Everest because of the overcrowding in Nepal and the surge of inexperienced climbers.

Nepali officials said the trekking companies are the ones responsible for safety on the mountain.

Mr Ghimire said the government was not inclined to change the number of permits. "If you really want to limit the number of climbers," he said, "let's just end all expeditions on our holy mountain."

To be sure, the race to the top is driven by the weather. May is the best time of the year to summit, but even then there are only a few days when it is clear enough and the winds are mild enough to make an attempt at the top.

But one critical problem this year, veterans said, seems to be the sheer number of people trying to reach the summit at the same time. And since there is no government traffic cop high on the mountain, the task of deciding when groups get to attempt their final ascent is left up to the mountaineering companies.

Climbers themselves, experienced or not, are often so driven to finish their quest that they may keep going even if they see the dangers escalating.

A few decades ago, the people climbing Everest were largely experienced mountaineers willing to pay a lot of money.

But in recent years, longtime climbers said, lower-cost operators working out of small storefronts in Kathmandu and even more expensive foreign companies that do not emphasise safety have entered the market and offered to take just about anyone to the top. Sometimes these trips go very wrong.

From interviews with several climbers, it seems that as the groups get closer to the summit, the pressures increase.

Experienced Lebanese mountaineer Fatima Deryan was making her way to the summit recently when less experienced climbers started collapsing in front of her. Temperatures were dropping to minus 30 deg C. Oxygen tanks were running low. And roughly 150 people were packed together, clipped to the same safety line.

"A lot of people were panicking, worrying about themselves - and nobody thinks about those who are collapsing," she said. "It was terrible."

NYTIMES