In the second part of The Godfather trilogy, there is a scene where the underworld boss Michael Corleone, devastated by the treachery of his brother that nearly costs him his life as well as that of his wife, approaches his dying mother with a question: In trying to be strong for your family, can you end up losing it?

Mama Corleone, not comprehending the import of the question, is innocent in response: But you can never lose your family!

With that assurance in mind, Corleone later passes a death sentence on his sibling, telling his most trusted bodyguard: "I don't want anything to happen to him while my mother is still alive."

Every time I think of India's tireless Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his hard-driving, full-court press style of governance, those words from Mama Corleone come back to me.

Mr Modi's story is well known. From tender years, he has forsaken his family of origin to be protected and reared by his family of orientation, the Hindu nationalist RSS organisation, living a spartan, bachelor existence and absorbing values that include putting nation above the individual. His record of development-oriented rule in his home state, Gujarat, helped elevate him to national power.

Yet, at the apex of his political career, comes the troubling question: In trying to save his nation, or, some would say, salvage it after the excesses of one of the most corruption-filled decades in its independent history, could Mr Modi end up actually damaging India?

The question needs to be asked because the tendrils of bad news coming from different directions is piling up as a smog over the world's most populous nation and Asia's No. 3 economy.

The US$2.5 trillion (S$3.4 trillion) economy, rather than radiating energy, is wheezing like an asthmatic in winter. Recent data suggests that it no longer can claim to be the fastest-growing. Job creation in the three years of Mr Modi's rule has halved from what it was in his predecessor's final years. Gross fixed capital formation has dropped alarmingly in a little over a year from 30.8 per cent of gross domestic product to 25.5 per cent, indicating an investment collapse redeemed only partly by a widening flood of foreign direct investment. Foreign policy is adrift and ties with the United States, once advancing rapidly, are floundering. The China relationship, particularly, is cause for worry.

STRAINED SOCIAL FABRIC

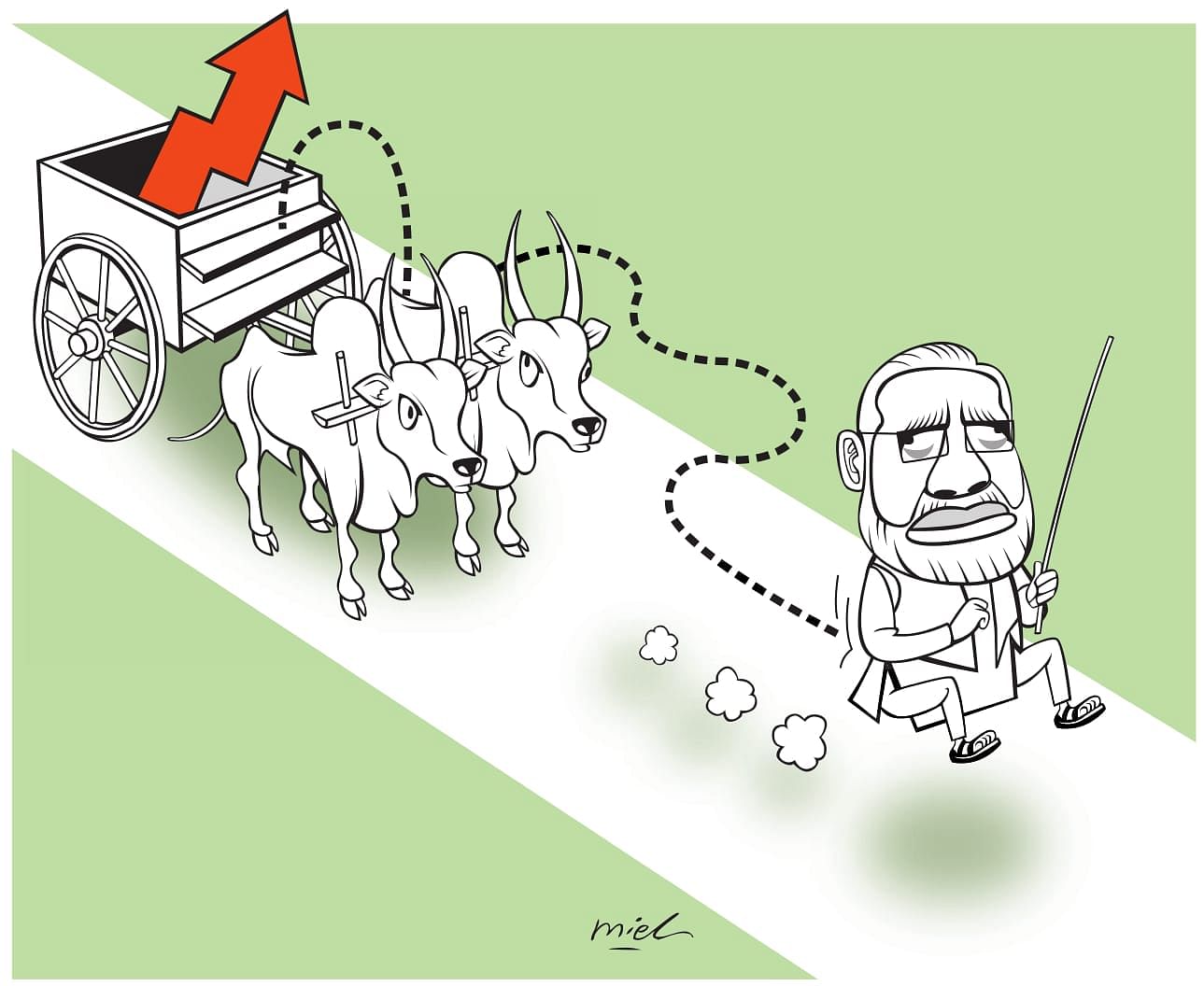

Most dangerously, India's social fabric is under strain as lumpen elements claiming to represent the Hindu faith target minorities, encouraged by a variety of factors, including the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party's endorsement of protecting the cow as a valued totem of the Hindu faith. As the question of whether eating beef is taboo for Hindus is itself a matter of debate, many perceive it as a barely concealed gambit to target minority groups, millions of whom not only consume beef but depend on the leather trade for a living.

Often this descends into farce. On Sunday, four government officials from the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu were attacked by cow-protecting vigilantes in northern Rajasthan who thought they were taking the bovines for slaughter. In truth, they were taking the cows for a breed- improvement programme in their home state. For each of these, Mr Modi cannot escape a measure of responsibility.

Without question, Dr Manmohan Singh - so tellingly described by his former media adviser as an "overrated economist and underrated politician" - bequeathed Mr Modi an economy that can only be described as a poisoned chalice.

In Dr Singh's last years, the nation was caught in the midst of one paralysing scandal after another. Misdirected, state-guided lending burdened India's state-run banks with massive non-performing loans. A culture of subsidies had taken root in the hinterland, sapping economic energy. Indians were salting away money overseas.

Into the breach stepped Mr Modi. Tightening up on government spending and going after tax evasion and the pervasive corruption in government, he displayed an admirable determination to fix things. His government has been scandal-free. Government staff are at their desks on time. And it is known that no one works harder, or longer, than the Prime Minister himself.

DRAGS ON THE ECONOMY

Still, the fiscal tightening took place amid a broader scenario of poor monsoon rains in consecutive years, dragging on the rural economy whose demand feeds industry. And, just as in Mr Xi Jinping's China, the anti-corruption drive also contributed to the growth slowdown by sapping the animal instincts of business.

Then, last November, Mr Modi, ignoring advice from the central bank and every notable economist in the country, went for a stunning manoeuvre of cancelling high-denomination currency notes. The move was kept secret and executed with the assistance of a tiny group of bureaucrats sworn to secrecy that even his Cabinet did not know until the last minute.

While the note-cancellation, painted as an attempt to check corruption, improve tax collection and squeeze funds flowing to terrorist groups, had a political windfall - the BJP swept the state elections in politically vital Uttar Pradesh as voters credited the Prime Minister with a well-meant, if flawed, move - the demonetisation is now recognised as a failure for all its stated aims.

Alarmingly, there is evidence that it delivered a massive shock to the entire economy, but most severely in the hinterland, where cash is king. Producer prices have dropped alarmingly, causing rural immiseration.

The result has been a wave of farmers' protests recently, often put down with state violence, that has led several BJP-ruled states to hurriedly announce loan waivers, weakening not only government finances but also the credit culture.

FOREIGN POLICY

Mr Modi's go-it-alone ways have, perhaps, caused most trouble on the foreign-policy front. Starting from the day he took charge - he invited the "prime minister" of the India-based Tibetan "government in exile" to his installation ceremony, along with the heads of other South Asian governments - his attempt to score a more assertive foreign policy than the nuanced one of his predecessors has had mixed, if not troubling, results.

Ties with China are at their most brittle in a generation, and Beijing has been emboldened to disregard Indian concerns and tighten its all-round relationship with Pakistan significantly on its all-important western flank. Mr Modi has also looked somewhat amateurish in his fevered embrace of the US and Japan, a policy that has clearly put off longstanding strategic partner Russia and is now at a standstill, thanks to the new man in the White House.

A lot of India's troubles, therefore, stem from Mr Modi's personality. People familiar with Mr Modi's working habits speak of a man who tends to go deaf when inconvenient truths are posited, one who is most comfortable working with a tight cabal of officers who rarely contradict him. That, however, leaves the Prime Minister's Office more as an echo chamber for Mr Modi's demanding thrusts rather than an elite college that throws up well-considered policy options as required for the leader of a vast and complex nation.

Equally, the stress to the hard-stitched Indian social fabric is worrying.

After seven decades of independence, the national glue acquired with such difficulty is under strain as Mr Modi, who proved so tough against fringe Hindu elements while he was a provincial chief minister, seemingly turns a blind eye to their depredations. Under him, Indian nationalism's aperture is being shrunk to one that speaks mostly to the Hindi-speaking "cow belt" of the country's heartland and a patronising attitude towards the rest of India, including its southern states that are now its main economic engines.

Nothing underscores this as much as the decision to elevate Mr Yogi Adityanath as chief minister of populous Uttar Pradesh, after the BJP's stunning electoral triumph in the state on the back of Mr Modi's hectic campaigning. Mr Adityanath has been a polarising figure in state politics and a mascot for strong-arm Hindu sectarianism. To the respected political thinker Pratap Bhanu Mehta, this move, above all, signalled that the BJP "will now be dominated by extremes, its politics shaped largely by resentment than hope, collective narcissism rather than an acknowledgement of plurality".

Mr Modi's dazzling energy, his deep commitment to India and his aura of incorruptibility and efficiency may strengthen the Hindu nationalists who are his family of orientation. But, in so doing, there is a real risk that he may weaken the India he sprang from and even end up losing it.