-

210 sq km

-

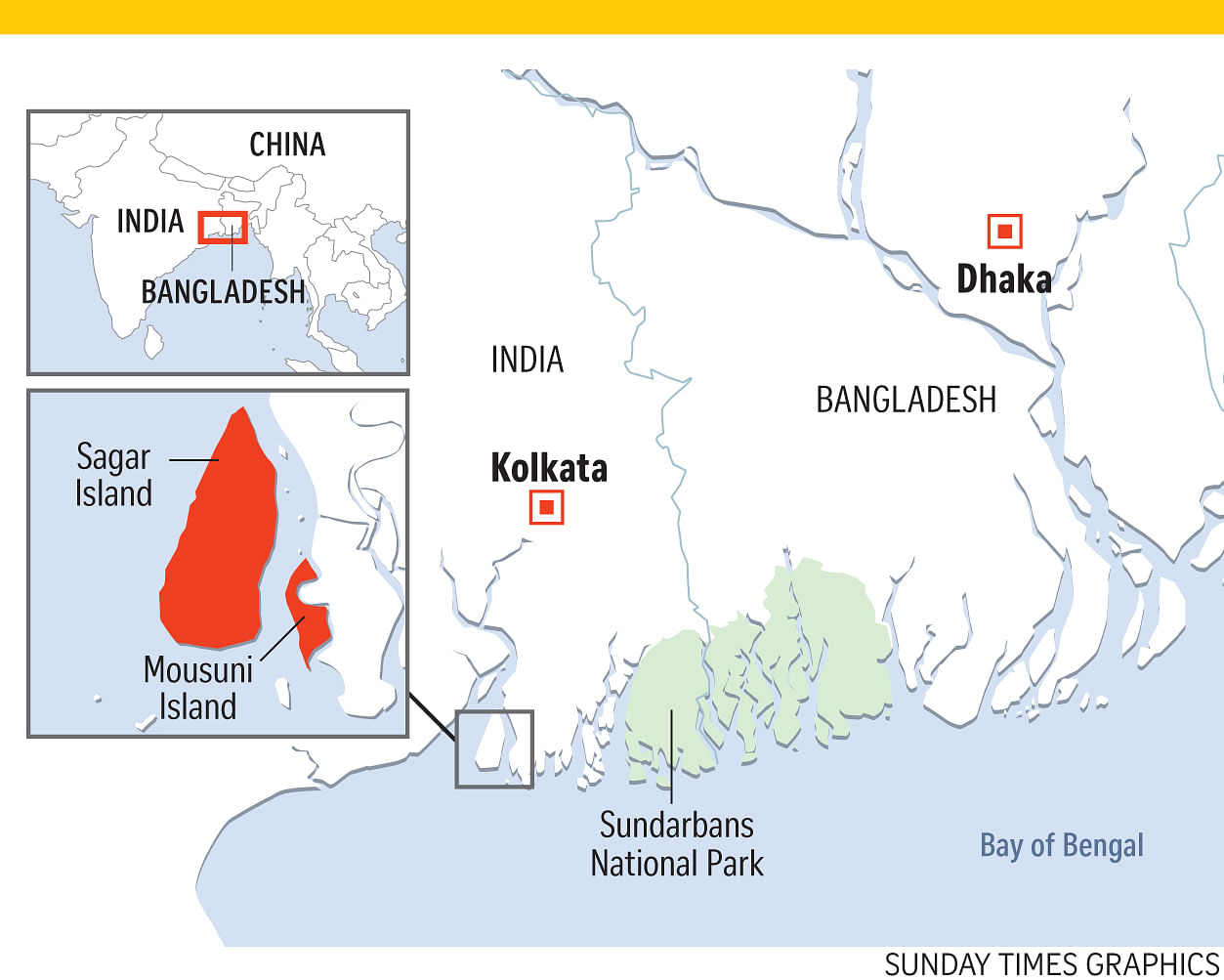

Land mass lost in the last 40 years among islands in the Sundarbans, home to over 4.5 million people and which stand, on average, about 2m above mean sea level.

-

37 million

Estimated number of people from India who will be at risk from rising sea levels by 2050, according to the Asian Development Bank.

Climate refugees: How extreme weather is forcing people to move

Homes, lives are swept away

Broken and battered embankments attest to the power of a sea that pounds the islands of the Sundarbans every day along the coast of West Bengal in India. Locals are fighting a losing battle as the sea devours homes, farmlands and the islands themselves.

A wily cat out to get her fish is not the only intruder Ms Akhtaroon Bibi has to fend off.

She is also busy mounting a battle against the growing appetite of the waters of the Bay of Bengal that are after her house. And things are not going her way. Ms Bibi, a single woman on Mousuni, an island in the Sundarbans delta region, has lost the first round.

The 40-year-old's mud house was destroyed a year back by the raging sea, which has been edging in closer in this part of India that has been deeply scarred by rising sea levels. "Water would come in from the doors and windows. I just couldn't stop it," she says, standing on the same spot next to her new brick house that has been built with government support.

Even though it has been built on a raised patch, there is no certainty how long it will hold.

"One way or the other, the water will come in to this house too and take it away," she adds, resigned to the inevitable fate of becoming a climate refugee.

Poor and with no means to buy a plot farther inland, Ms Bibi does not know where she will end up.

It is an all too familiar story in the Sundarbans. This region has recorded an annual sea-level rise of 12mm, nearly four times the global average, according to Dr Sugata Hazra, a professor at the School of Oceanographic Studies at Jadavpur University in Kolkata. This is bad news for a region that is home to more than 4.5 million people and stands, on average, about 2m above mean sea level. Its islands have already lost 210 sq km of land mass in the last 40 years.

Dr Hazra had estimated back in 2002 that 69,000 people will have to move from the Sundarbans by 2020 because of climate change. This figure, he says, has already crossed 60,000. "People who are not responsible for climate change are the worst sufferers of climate change," he says.

Near Ms Bibi's house, children play football on the vast coastal tract cleared by the encroaching sea. Decapitated palm stumps, some with their gnarled roots exposed, dot the scene. A playground at low tide, it turns a watery graveyard at high tide. And while the living drown, the dead are woken up - a local graveyard is inundated regularly, bringing up pieces of skeletons.

Before the next deluge sets in, Mr Sheikh Sofi is evacuating his frugal belongings. He pegs tarpaulins to the house in a vain attempt to prevent the waters from coming in. "Today there was knee-deep water in my house. I cannot stay here another night, my children will be washed away," he says hurriedly.

For now, he is moving to a relative's house. In the long run, he is certain of becoming a climate refugee all over again. "This house was built in 2008 after I lost my earlier house," he adds, pointing in the direction of the sea.

The sea has been notoriously hungry here, nibbling away at these islands. A 2015 study in the Journal of Coastal Sciences reported that while Sagar, another island in the Sundarbans, had lost 7.37 sq km between 1979 and 2011, Mousuni has been whittled down by 3.82 sq km in the same period. Some islands, like the once-inhabited Lohachara, are now completely inundated most of the time.

An ecological cost is also being exacted. Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest ecosystem, acts as a nursery for roughly 90 per cent of the aquatic species found in the east coast of India, says Mr Ratul Saha, the landscape coordinator for Sundarbans at World Wide Fund for Nature-India. The lives of millions of fishermen directly depend on its continued health.

"It also serves as a physical bio-shield," he adds, cushioning the area from the cyclones that could threaten the lives and livelihoods of millions along the coastline. Saline water incursion has made both agriculture and fishing, which have been the region's economic mainstays, unproductive in many areas. A third of Mousuni, for instance, has become uncultivable. This is a phenomenon that is aggravated by cyclones here, like Aila in 2009, that created a storm surge of around 1.5m and inundated vast tracts of coastal land.

With little to sustain them, men here have moved out in droves. Everyone on these islands has either a family member or a friend working in the southern Indian state of Kerala, where emigration to the Gulf countries has created a labour shortage. "We are being forced to go out because embankments are not being built. If the government builds them, we can rear fish here or grow vegetables. We would not have to go so far in search for work," says Mr Dil Mohammed Sheikh, 28, a resident of Mousuni who works as a construction worker in Kerala.

This emigration has bequeathed many women-only households in this region. Ms Sarifa Bibi, a 50-year-old widow, who lives with her daughter-in-law Mamoni, is one such family on Mousuni. They get by on less than $100 a month, much of it sent by her son Rabibul Shah from Kerala. Less than 80m from the courtyard of their unpainted brick house is a broken embankment that lets in saline water into their freshwater pond and field.

It is a worrying view to wake up to. "Today the water came right up to here," Ms Mamoni says, gesturing to a spot a few metres away from her house. "What's the certainty that it won't come into our house tomorrow?" she adds.

Meanwhile, the hardy locals have learnt to salvage whatever they can. Beyond the broken embankment, some children are scouting the retreating waters of the low tide. Their backs hunched, they keep their eyes peeled for an odd ripple caused by fluttering small fish that have been drawn out from ponds inland. An hour's hard work may just yield a small handful but it is a helpful addition to the family's dinner.

In Sagar, less than 100m away from an embankment that crumbles with every whiplash from the waves, is a mud house that lies abandoned. Those with means to buy land away from the sea have already done so.

Dr Hazra says things look bleak for Sundarbans as global carbon emissions - which raise sea levels - seem set to keep climbing. "You cannot stop rising sea levels locally."

As the embankments are breached, one after another, it leaves relocation, together with other measures such as skill development, as the only sustainable way to help climate refugees.

The state has helped some people relocate, on a case-by-case basis. Fisherman Sheikh Mohinuddin, 45, moved out of Mousuni four years ago to a plot he received from the government farther inland on the much bigger island of Sagar.

"While I am in a better condition, I don't earn as much as before. I earn around 100 rupees (S$1.88) every day," he says, adding that he is repaying a debt of 20,000 rupees incurred to construct his new house.

While India demands finance and technology from rich countries to green its economy, the plight of the Sundarbans goes unnoticed.

"India has not highlighted its climate change vulnerability despite being ranked among the most vulnerable," says Mr Harjeet Singh, the global lead on climate change for ActionAid. "This has created an impression that India is not vulnerable," he adds.

The Asian Development Bank estimates that around 37 million people from India will be at risk from rising sea levels by 2050.

The morning after evacuating his house, Mr Sofi returns to check it out. Waves have begun to lash at its walls again with the incoming high tide. "Abar aashben (come again)," he tells us, ironically as the sea water swirls around his ankles.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on November 04, 2018, with the headline Homes, lives are swept away. Subscribe