KUALA LUMPUR • Their feet nimbly tapping out a whirl of steps, the children twirled and swirled to the lively music of Malaysia's Portuguese Eurasian community.

They earned oohs and ahhs and laughter as they cajoled the seated guests to join in the dancing at a recent cultural event in Kuala Lumpur.

Made up of schoolchildren, the dance troupe is part of efforts by the country's Portuguese community, whose ancestors settled in Melaka in the 16th century, to preserve its eroding culture.

The loss is keenly felt, particularly in the decreasing use of their native tongue - Melaka Portuguese or Cristang, a Creole language.

With a population of around 1,000, the Melaka Portuguese Settlement - where the young dancers are from - has the highest concentration of Cristang speakers, but many of those below 45 are not fluent.

Cristang is not alone in its plight. Minority languages are rapidly being replaced by English, Malay and Mandarin - the dominant tongues taught in Malaysia's schools.

Many Malaysians, like those from the Portuguese Settlement, are trying to save the languages of their ancestry for fear of losing their unique identities and heritage. They have recorded their languages in books, enshrined them in dictionaries and popularised them through podcasts, to encourage more people to use them.

-

136 Number of languages in use in Malaysia.

- 80% Proportion of languages that are considered endangered.

Dr Stefanie Pillai, dean of the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Malaya, said some languages are spoken by fewer than 50 people.

Of the 136 languages in use in Malaysia, some 80 per cent are considered endangered, according to the Ethnologue Report, a database of the world's 7,000-plus languages.

An "endangered" language is one where the speakers are mainly elderly people, said Dr Pillai.

The one spoken by the Orang Kanaq of Johor, an Orang Asli group numbering just 62 at the end of the 1990s, has only 34 items left on its word list and is considered dormant, said Dr Paolo Coluzzi, a researcher at the same faculty. He said two languages had become extinct, Wila' (Lowland Semang) and Ple-Temer.

LANGUAGES, CULTURES, VALUES

The decline has triggered efforts at preservation, at least among the larger ethnic groups.

Cristang, for one, has found many protectors (visit https://elar.soas. ac.uk/Collection/MPI130545 for a sample; registration required).

The dance troupe is one initiative. The kids were taught in Cristang, so they soon spoke it fluently, albeit with a hefty mix of English words.

Dr Pillai, whose mother is Portuguese-Eurasian, worked with the community to produce a CD of Roman Catholic prayers in Cristang. This year, they published a book called Beng Prende Portugues Malaka (Come Let's Learn Melaka Portuguese) as an aid for teaching the language more systematically.

"Our team discussed the spelling system at length to reflect the community's culture," Dr Pillai said.

She noted that languages have their own value as the bearers of a community's culture and values. Having their own language also enables minority communities to feel they have a place in their country.

"We are all Malaysians, but a sense of identity is very important. Sometimes, in Malaysia, assertion of an ethnic identity is made out to be a bad thing, but it's not," said Dr Pillai.

Madam Teresa de Costa, 72, is now relearning Cristang because she felt she had lost a part of her identity when she let it slide in favour of English. "I felt I had missed out, but it's slowly coming back to me," she said.

GROWING AWARENESS

As a community leader striving to preserve his language, Mr Ricky Ganang strongly agrees about the relationship between language and identity in a community.

He is from the Lun Dayeh, a minority ethnic group in north-eastern Sabah whose population stands at around 9,000; there are 20,000 more if the related Lun Bawang group in Sarawak is included.

He said that even though Lun Dayeh and its variants in Sarawak are still widely spoken, younger people increasingly speak Malay at home, because of mixed marriages and because parents want to prepare their children for school.

"But once they lose the chance to learn the language as a child, it is lost forever," said Mr Ricky, 66.

Worried his culture would vanish, he has recorded the stories and songs of his people since he was 17. Now retired, he has turned his notes into books about his community's folk tales and oral traditions.

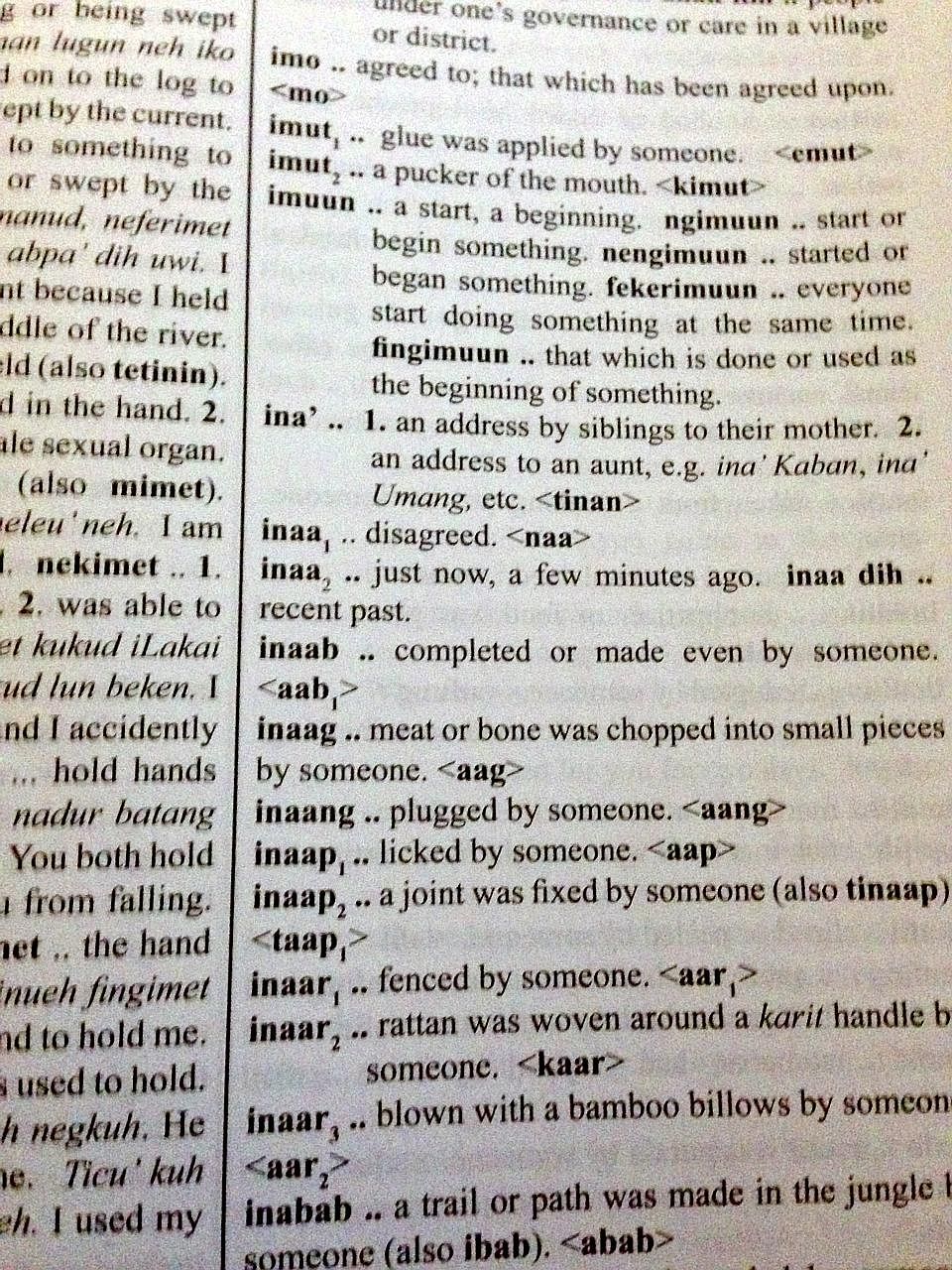

In 2015, together with two American academics, he produced a Lun Dayeh-English dictionary that was snapped up by parents keen to teach the language to their children. He is now working on a Lun Dayeh-Malay version as Malay is more widely spoken in Sabah than English.

"I did it out of concern for our language. To preserve it, we have to write it down," he said.

He added that more people are now aware of the loss, hence the demand for the Lun Dayeh dictionary. Kindergartens are starting to teach the language as well.

NOT JUST THE MINORITIES

In Penang, the dominant Chinese community worries about the erosion of Penang Hokkien, derived from the language of China's Fujian province. Speakers say it differs in intonation and vocabulary from the Hokkien spoken in southern Malaysia and Singapore, where many words were borrowed from Malay.

"The difference is clear to Hokkien speakers, but not to the point where we can't understand one another," said Mr John Ong, a United States-based graphics designer born in Penang who runs a popular weekly podcast in Penang Hokkien.

The language is still widely used in Penang but mainly among the elderly in the community.

Said Ms Tan Siew Imm, a former university English lecturer and a third-generation Penang Hokkien: "I have noticed many Chinese Malaysian students use Mandarin, and stop using their mother tongue."

She cited a survey of 800 Chinese students in Penang, which found 42 per cent used Penang Hokkien as their first language, and 70 per cent used it only with their grandparents. The survey was done in 2010 for a dissertation by Mr Sim Tze Wei for a master's in language documentation and description at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Ms Tan wrote a Penang Hokkien dictionary last year in hopes that a written form of her language would help keep it alive. Some 700 copies have been sold.

HOKKIEN PODCASTS

Other Penangites are using popular culture to revitalise the language.

In May, Malaysia's first Penang Hokkien movie, You Mean The World To Me, garnered rave reviews for its gritty story of family ties as well as its use of a minority language.

Director Saw Teong Hin told The Star in April that the choice of language was vital as the story was set in Penang, and Penang Hokkien was the language of its characters.

Mr Ong feels pop culture is key to making Penang Hokkien "cool".

"When I was growing up there in the 80s and 90s, we were not allowed to speak Hokkien in school. It was seen as a language that the uneducated would use," he said.

But when he moved to the US, he missed its sounds. He started his Penang Hokkien podcast in 2005 - at the age of 31 - when he uploaded his light-hearted conversations with a former schoolmate.

To his surprise, within a year, hundreds of people were listening in.

It was then that he decided he could do more, and began recording regular podcasts with Hokkien speakers. Recently, his guests have included Mr Saw and several cast members from the movie, including Ms Yeo Yann Yann, a Malaysian actress based in Singapore.

Mr Ong now has over 600 podcasts at penanghokkien.com and 3,000 to 4,000 regular listeners.

Despite these efforts, he said, Penang Hokkien is still fading as the young barely speak it. If it disappears, a part of Penang will disappear along with it. "That's a scary and sad thought," he said.

While cultural identity is valuable in itself, it also has economic value. Dr Pillai noted that tourism is often about experiencing different cultural identities, so keeping languages alive can have economic benefits.

But economic benefits aside, language diversity is something that many Malaysians want to preserve.

"It would be a dull world with only one language," said Ms Tan, who has become a staunch defender of the need to preserve Penang Hokkien.