JAKARTA - Efforts by Indonesia to curb rising cooking oil prices at home by messing with the free market have disrupted the market and any positive outcome would not last, experts have argued.

What Indonesia needs is simple and straightforward policies that will ensure affordability and availability of cooking oil, said Dr Fadhil Hasan, head of foreign affairs at the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (Gapki).

"Let the price of cooking oil follow the market price. Protect the lower-income group by giving them direct cash transfers to compensate for the high price," he told a discussion on Wednesday (June 8) organised by Jakarta Foreign Correspondents Club (JFCC).

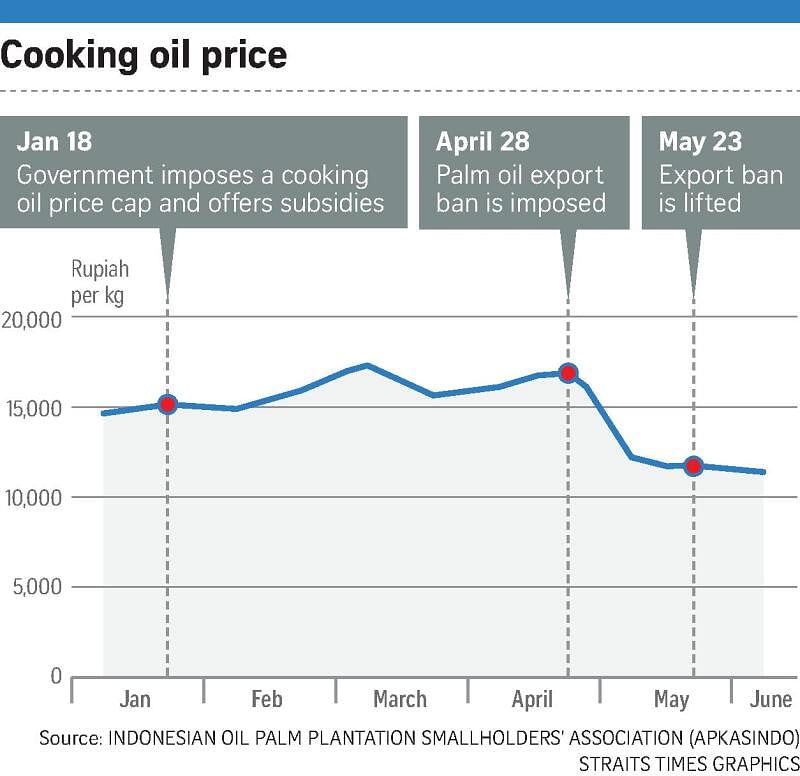

Indonesia early this year imposed a price cap of 14,000 rupiah per litre (S$1.33) on cooking oil sold to consumers, after prices stayed stubbornly high for more than four months. The measure led to distributors and retailers illegally hoarding stocks to avoid selling the merchandise at low price.

Several measures then ensued, including dropping loads of subsidised stocks in the market, requiring producers to allocate at least a fifth of their products for domestic supply and telling them to support price subsidies. None of these proved effective in bringing down the prices.

Around mid-March, scarcity peaked and prompted the government to leave the price of packaged cooking oil, a premium product, to the market in a bid to ensure its availability.

Packaged stocks started to reappear on store shelves, but with prices reaching 25,000 rupiah a litre. Bulk cooking oil price also went up, reaching above the regulated price of 14,000 rupiah a litre and it was hard to find the stock in the market.

The government found out that the bulk cooking oil that it sent to various locations were targeted by recalcitrant distributors who packaged the stocks into bottles, put labels on them and resold them at premium prices.

President Joko Widodo then made a surprising move by announcing export bans on all palm oil products that took effect on April 28. Again, this prompted a repercussion: many oil palm farmers selling fresh fruit bunches - raw material to make crude palm oil - to processing plants were either turned away or offered very low prices.

The government reinstated palm oil exports on May 23 after the average price of cooking oil began to fall.

But export shipments may begin only two to three weeks at the earliest after the export permit is issued, provided there are available cargoes, said Mr Eddy Martono, secretary-general of Gapki.

"Exporting companies have to reopen communication with importers overseas after a hiatus, then finding cargoes take time as providers might have ongoing contracts to fulfil," Mr Eddy told The Straits Times.

Experts and associations have cautioned against disrupting the free market, as doing so would cause an unexpected chain reaction.

At the JFCC discussion, Mr Gulat Manurung, chairman of Indonesia's association of palm oil farmers (Apkasindo), pointed out that the prices of fresh palm fruit bunches have never fully recovered since the export ban was announced.

"If you disrupt one system, the problem spreads everywhere," he said.

Dr Tungkot Sipayung, executive director of Palm Oil Agribusiness Strategic Policy Institute, took issue with the continued subsidy on bulk palm oil price that the government requires the private sector to bear the costs. This amounts to going against how the free market works, he said.

And this happened while companies are facing surging fertiliser costs, which today account for more than half of total production costs, he added.

The Oil Palm Plantation Support Fund Management Agency, which currently collects fat export levies and accumulated billions of dollars from exporting palm oil companies, should cover the subsidy costs, while producers should be asked to help ensure only stock availability at home, Dr Tungkot said.