-

FACTS AND FIGURES

-

• Kuala Lumpur has 71 gazetted buildings, according to national heritage NGO Badan Warisan Malaysia.

• Of these, 28 are buildings located within the compound of Malaysia's police academy, commonly known as Pulapol. In addition to the buildings in Merdeka Square, other gazetted sites include the city's old railway station, St John's Institution and Merdeka Stadium.

• Only five of the gazetted buildings are privately owned. These are the Majestic Hotel, St Mary's Cathedral, Telekom Museum, Vivekananda Ashram and KL-Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall.

• The National Heritage Department was given a one-off sum of RM30 million from the Treasury in 2006, after the National Heritage Act 2005 came into effect. According to a report by The Star last month, only RM100,000 (S$31,700) of this sum is left.

• Buildings that are gazetted under the Act are legally protected from demolition or destruction.

WORLD FOCUS

Kuala Lumpur's heritage buildings under threat

Misguided spending, poor maintenance and bad planning have left these icons in disrepair

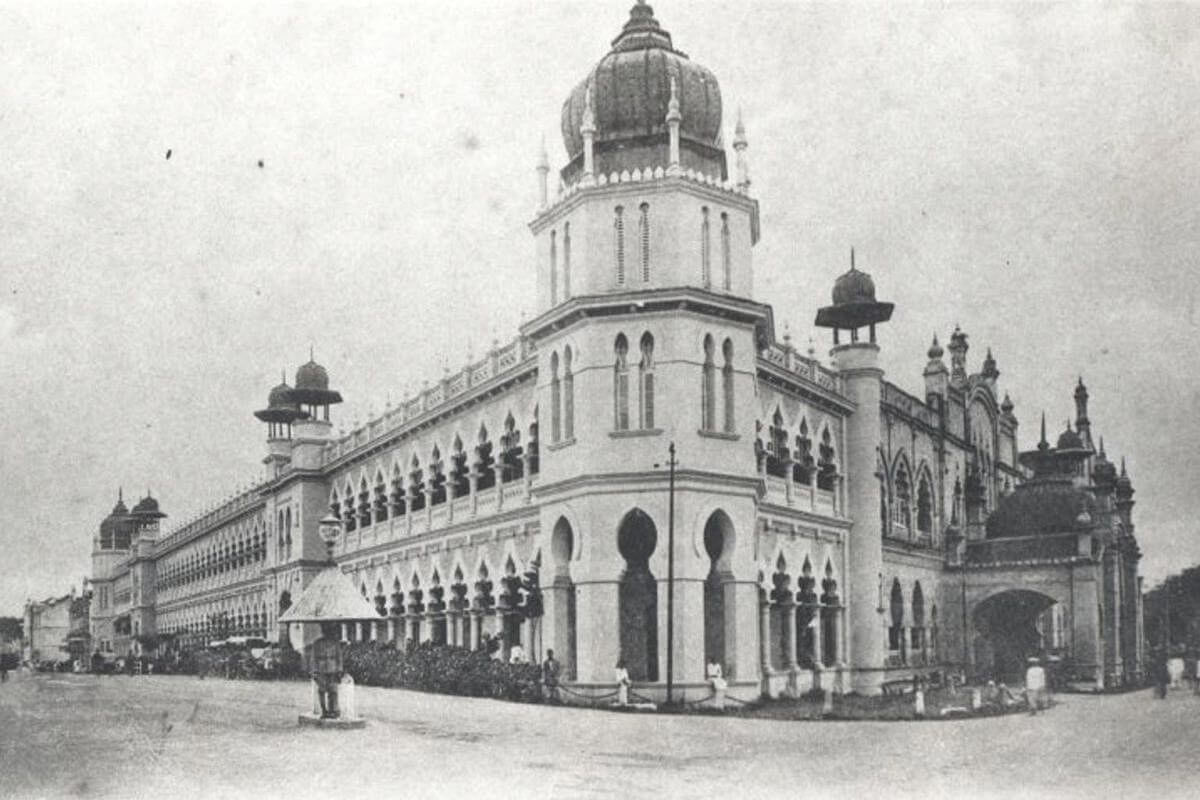

While strolling around Kuala Lumpur's historic Merdeka Square, admiring the copper-domed red brick of the Sultan Abdul Samad Building and its famous clock tower, conservationist Mariana Isa cautioned the small group of architects with her.

"What we'll see next will pain you," she said.

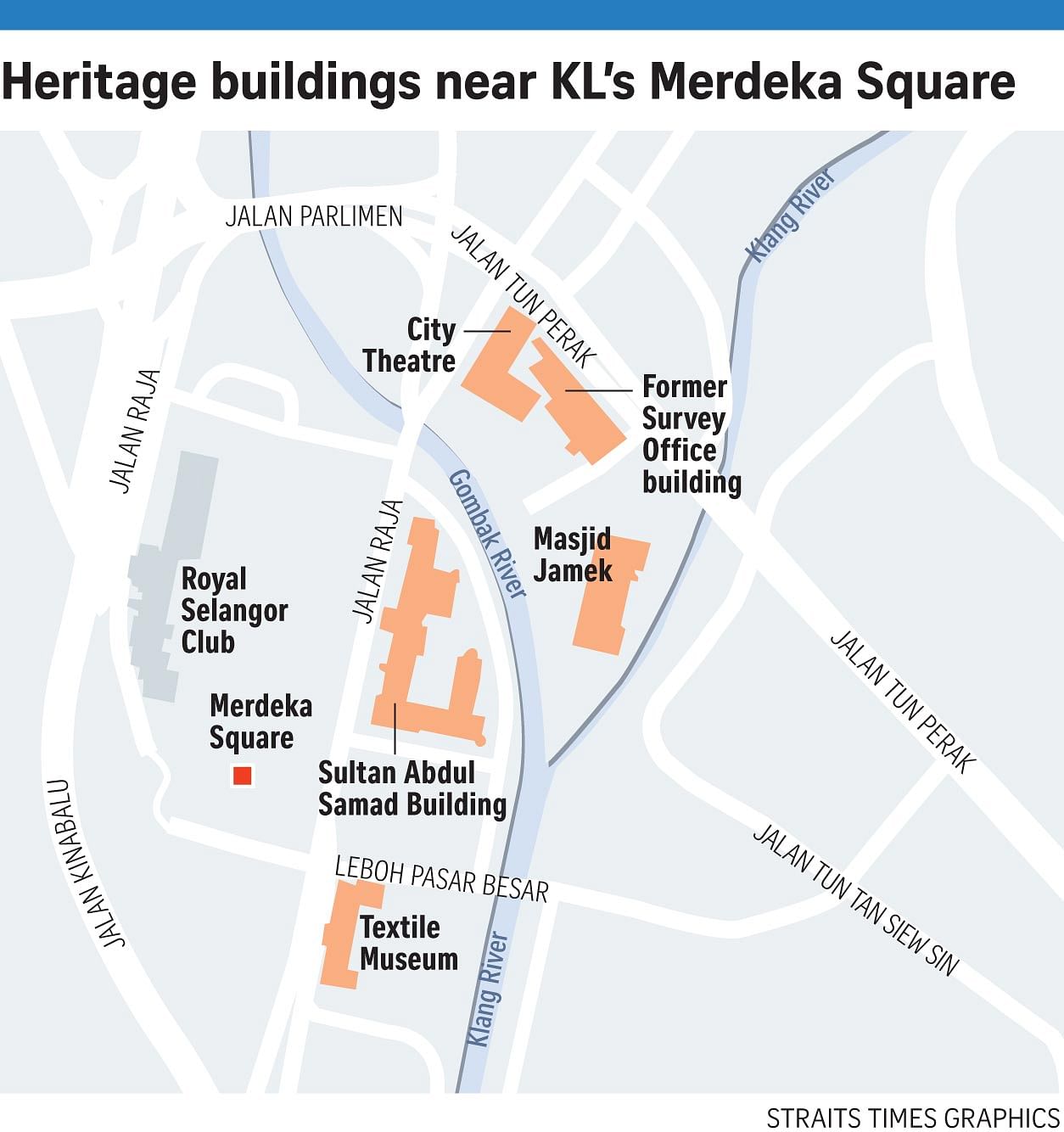

Just steps away, a glass and concrete bridge straddles the Gombak River. Its industrial design clashes with the intricate 19th-century Mughal arches of the surrounding heritage buildings, crushing any tourist's hopes of capturing a postcard- perfect view of what the capital city looked like a hundred years ago.

The bridge represents much of what has gone wrong with the city's heritage preservation: misguided spending, bad planning and a failure to consult with experts in the field.

It was built this year as part of an eye-watering RM4.4 billion (S$1.4 billion) government plan to rejuvenate the city's rivers and their surroundings. Some RM255.5 million of this River of Life project has been allocated to upgrade the water treatment system and beautify the riverside areas in the heritage zone. However, conservationists observe that most of it is spent on ill-conceived new-builds and none on preserving historical landmarks, which are in various states of disrepair and ruin.

Adding insult to injury, the changes wrought by the river project are destroying the historical value and spirit of KL's landmarks, say architects and conservationists.

Merdeka Square in Jalan Raja is the quintessential throwback to the region's colonial past, flanked by a cricket pitch, the Tudor architecture of the Selangor Club and the stretch of grand domed buildings which include the textile museum, the city theatre and the now-vacant former Federated Malay States survey department office.

Merdeka Square is where Malaysians gather for the annual independence day parade and where tourists flock to, beckoned by travel brochures. But a closer look reveals that the nationally gazetted buildings have seen better days, a condition highlighted by The Star newspaper last month.

Chipped walls, water seepage, broken doors and a fallen spire from a dome are small but clear signs that Malaysia's pride is under siege.

A check by The Straits Times two weeks ago revealed that the brick walls of the Sultan Abdul Samad Building were unprotected from ongoing construction work on the river. They were also unprotected from nature: algae and plants could be seen growing in the crevices.

"The biggest problem is when you start seeing plants growing on the roof. The building will soon fall apart when there's no maintenance," said Mr Steven Thang, council member of Malaysian Institute of Architects (PAM).

Tourism Minister Nazri Aziz has said the buildings fell into neglect due to a lack of funds. "We have applied for RM150 million, but have yet to receive anything from the Treasury," Datuk Seri Nazri told The Star in March.

But conservationists are mystified how hundreds of millions of ringgit are available for the river project, but not to preserve these centuries-old buildings.

"If the government gives a small percentage out of the sum (for the river project) to preserve the buildings bit by bit, it can save them the long-term damage," said Mr Thang, who heads PAM's heritage conservation committee. He adds that algae growth on walls is a sign that a building has been left untended for between one and two years.

Meanwhile, the group led by Ms Mariana walk past the former survey office and see that its famed 122m-long arcade is strewn with rubbish. Empty water bottles and rags on the floor indicate that the city's homeless have made this 107-year-old vacant building their temporary lodgings.

"There's no long-term planning. When there was a new government building, they moved into it and left this empty," said Ms Mariana, a committee member at the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos).

Bad planning also affects the aesthetics. "Except for the heritage buildings, the ambience of the area has lost its originality," said Mr Thang. "The government is just designing new things around the buildings."

Ironically, a key culprit of these changes is the much-lauded effort to rejuvenate the areas around the city's rivers. Modelled on similar efforts for the Thames in London and Seoul's Cheonggyecheon River, the project has brought in modern structures, which conservationists say are jarring against the backdrop of heritage sites.

One of these new installations, just across the road from the survey office building, is a rectangular structure with cascading coloured water around it and a lurid LED panel with a clock counting down to 2020 - the year Malaysia expects to achieve the developed nation status. Costing nearly RM10 million, the structure replaces a kitsch green fountain adorned with pitcher plant carvings that also drew much flak when it was built.

The surroundings of the city's oldest mosque, Masjid Jamek, have not escaped similar treatment. While the government restored the mosque's original steps that lead to the river, it removed coconut trees, native to Malaysia, on its grounds and planted Middle Eastern date palms instead. Outside the mosque, colonial shophouses were torn down to make way for a canopy that mimics the giant umbrellas at Medina's famed Prophet's Mosque.

"The beautification projects and upgrading works have killed off the original spirit of the area," said Mr Laurence Loh, the architect behind the restoration of Penang's famed Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion, also known as the Blue Mansion. "The sense of place, history, memories. All of that is lost."

Malaysia has seen a renewed interest in heritage preservation in the last decade, partly driven by the Unesco World Heritage Site status granted to two cities, Georgetown and Melaka, both in 2008. The strict rules on conservation imposed by the world body help ensure proper planning and enforcement.

Mr Loh said the absence of a gazetted conservation plan in KL would lead to the destruction of heritage sites threatened by development and poor urban planning.

A 10-minute drive away is Carcosa Seri Negara. Built in 1896, it was the official residence of the first British High Commissioner to Malaya. In the 1980s, it was transformed into a colonial-themed hotel. The place has been closed to the public since January 2016 for refurbishment. To date, restoration works have not begun and the empty mansion is showing signs of dilapidation.

Conservation experts say there is plenty of local talent in the form of non-governmental organisations and specialist groups. But they have not been sufficiently consulted.

"The engagement has been superficial and it's not thorough," said Ms Elizabeth Cardosa from Badan Warisan, a non-profit heritage organisation. "We are perturbed by these additions. In conservation, less is always more," she added, referring to the new-builds in the Merdeka Square area.

The Federal Territories Ministry overseeing the buildings and upgrading works in Merdeka Square did not respond to requests for comment. The National Heritage Department, the agency tasked with maintaining gazetted heritage buildings, told ST that it could not provide answers as other government agencies are also involved.

Conservationists conclude that political will and proper management are core solutions to reviving Malaysia's colonial buildings. "It's not that nobody understands what heritage is… But what you see is how wrong intervention can cause an area to lose its sense of history," said Mr Loh.

"When you compare with Singapore's conservation plan, you see that it's not a national priority here."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on August 08, 2017, with the headline Kuala Lumpur's heritage buildings under threat. Subscribe