Some years back, a friend of mine won a literary prize. We celebrated.

Some days back, my colleagues and I were told we had won the Editor & Publisher Eppy Award for our news feature on life in the Rohingya camps - sharing the top global prize with CNN's coverage of illegal executions in El Salvador. We are still not quite sure how to react.

As journalists, this is a major validation of our work. But as our work involved writing about a million people displaced from their homes, about widows and rape victims now queueing up for rations and umbrellas, and about children who head households because their parents have been killed, it seems odd to celebrate.

On Aug 25, I received a WhatsApp message from Rohingya activist Mohd Eliyas, who sent me video clips of thousands of displaced men, fists raised, observing the first anniversary of the day death and massacre visited them in their villages in Myanmar. Since then, he has kept me informed of protests being organised against the barren hillocks of the camps, speeches demanding citizenship and, with a personal burst of pride, sent a photo of his child on a rented horse on a beach.

Any moment of joy is worth cherishing. But in the months since we returned from the camps at Cox's Bazar, little appears to have changed.

Perhaps the more sensational numbers that have defined this crisis in the eyes of the world have been given an update. The latest report by a consortium of international researchers says that 25,000 Rohingya were murdered in late August last year - not 10,000 as estimated earlier. It says that 19,000 women were raped. And from these numbers, the world tries to gauge the scale of the tragedy.

The numbers may be accurate or inflated. Our focus was very different.

-

About the awards

-

The Eppy awards are presented by Editor & Publisher to honour the best content on media-affiliated websites across 30 diverse categories.

All media companies that operate Internet services on the World Wide Web are eligible to take part, and the international contest is now in its 23rd year.

This year, The Straits Times (ST) tied with CNN for this top global award in the news feature category.

Informing ST of the win, Eppy Awards Committee chairman Martha McIntosh wrote: "The competition was fierce, there were hundreds of entries and the judges chose your submission as exemplifying the very best in its category."

Other winners this year include Bloomberg, The Boston Globe, USA Today and ESPN.com

We wanted to know about the lives - the half-lives, as we later learnt - of the survivors in the Kutupalong mega camp in Cox's Bazar. And we wanted their stories unfiltered.

To understand the history of the conflict and the situation on the ground before we left, we spoke to Mr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury, former Bangladeshi foreign minister who is now attached to the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. We also called five international journalists who had visited the camps and spoke to embassy and aid agency officials. Each told us that language would be a problem.

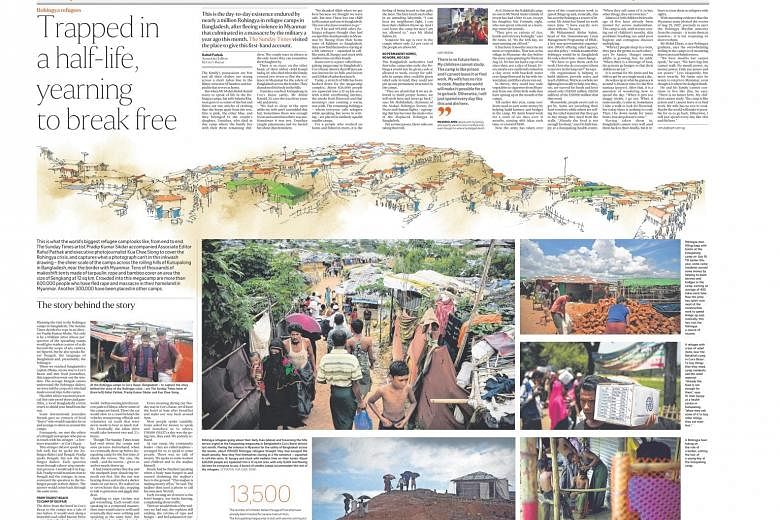

We added Mr Pradip Kumar Sikdar, a native Bengali speaker and a brilliant artist with our company, to the team. The camps were too sprawling for any camera to capture, so only Pradip's pen could capture its contours, we reasoned. Pradip was also to act as translator. Mr Kua Chee Siong, described by his boss as "an excellent shooter" was to take photos.

Our plans went out the window the day we landed in Bangladesh. A bright young reporter for The Daily Star in Dhaka, who had visited the camps on at least 10 occasions, freely offered advice: Buy cotton towels to cover your heads against the sun; buy footwear to withstand the slush; do not offer food or money to anyone in the camps or you will be surrounded by others; the Rohingya dialect is nothing like Bengali.

Like others before him, he, too, suggested hiring a "fixer" - a middleman who would help you find your way around the camps and translate for you. But he shared his misgivings with us. "If you want to speak to an orphan, they will find you orphans. If you want rape victims, they will find you rape victims. What you will never know is exactly what these people are saying and whether they have been coached."

Then we got lucky. We found a local freelance journalist who could speak Bengali and the Rohingya dialect. He did not want any money. He just wanted to hitch a ride with us to the camps from Cox's Bazar, so that he could file reports for his own newspaper.

After a few days in Cox's Bazar, I texted a friend to say: "This is simply the most gruelling assignment I have ever been on. We travel five to six hours a day to and from the camps. Our backs hurt. We try to spend seven to eight hours a day at the camps, which are totally chaotic. There is no one to lead you where you want and we don't trust the money-makers.

"Instead of using these people, who demand US$100 (S$140) a day, I have sought the help of a local Bangladeshi journalist. The guy speaks Rohingya, translates to Pradip in Bengali and he, in turn, translates to me in English. The sun is blazing hot and we don't eat all day since we've decided not to fall sick. That said, we have real, unsullied stories."

The stories revealed themselves to us over days. At first, we just took in the impressions and they were overpowering. One of us, who had given up smoking, snatched a cigarette and sucked deeply as soon as we stopped outside the camp to stop himself from throwing up. The shanties leaned against each other for miles. Dead, dark pools of water gathered after rains.

Each day, we would look at everything we had seen, heard and smelt - and try to see how it all fit together as a whole.

Each day, a story would die. We were told of the devastation that the rains would bring. Landslips did kill a couple of people, and the wind and water destroyed some huts - but in a million-strong township, did that really matter?

We were told that criminals lurked when darkness fell - but we saw the Bangladeshi army valiantly trying to pave roads and provide basic public lighting.

We heard whispers about prostitution. We were told of how majhees - community leaders - had been enriching themselves at the expense of other refugees and how several of them had been murdered. We saw a majhee thrashed before our eyes, but surely, this was a bigger story than petty corruption.

While I tried to join the strands together at night, I would envy Chee Siong and the brilliant photos he was taking, and Pradip, who was always smiling, taking pictures of his own and translating for me. This was until I realised how meticulously Chee Siong planned his pictures and how Pradip was - step by step - mapping out the vast township he would later draw.

The truth, which eventually dawned, was that there was nothing sensational about the Rohingya camps. It was a story chilling in its mundaneness, its repetition and its snuffing out of hope.

For the children, it was a life with no schools and sometimes no parents. Just bloated tummies that spoke of malnutrition and a stunning skill at marbles, which they played for hours on end.

With 300 people to one toilet, even relieving themselves was a chore for women. Teenage girls were kept locked inside their homes in the belief that this somehow safeguarded their modesty. They would sit beside a clay oven, and sweat and stink.

The men were not allowed to take up jobs as Bangladesh, a poor country that opened its doors to the refugees, now tried to protect the livelihoods of its own citizens. The refugees are stuck with endless hours on their hands. As one of them, Mr Nurul Amin, told us: "When it gets too muggy inside, I go out. When it rains outside, I come in. Sometimes I take a walk to look for firewood, but today, there is nothing to cook. Then I lie down inside for many hours, but sleep doesn't come."

But it is not just the slow days that are depressing. It is the increasing likelihood that they will stretch like this forever.

The diplomats and the academics that we spoke to said the Rohingya are too insignificant for regional powers to really rock the boat. China, India and Asean - each with some clout over Myanmar - have clucked their tongues and looked away.

For now, it suits everyone to act as if this is Bangladesh's problem and send some aid its way.

The Rohingya, people of rivers and farms, could be trapped on a tiny hillock for years to come. There may be nothing to celebrate, but we are still glad we told their story - warts and all - the way it revealed itself to us.