Despite President Xi Jinping's half-decade-long anti-graft campaign, low-level corruption remains a business reality for Singapore firms in China.

For a society where guanxi, or personal connections, can make or break a deal, wining and dining officials, suppliers and clients is very much an accepted, even expected, practice, especially in certain industries, says Mr Ching Mia Kuang, chief executive of corporate advisory firm Le Yu.

Mr Ching, whose firm advises Singapore companies entering the China market, says he has had to dissuade the occasional client from taking legally problematic actions, such as when one wanted to give a 1000 yuan (S$205) jiaotongka (transport card) to an official to expedite an approval.

A move like this would border on being a bribe and might have put the firm on the Chinese authorities' radar, says Mr Ching.

But news reports show that few Singapore firms fall foul of corruption laws, although Singapore's laws have provisions for extra-territorial powers over a Singapore citizen.

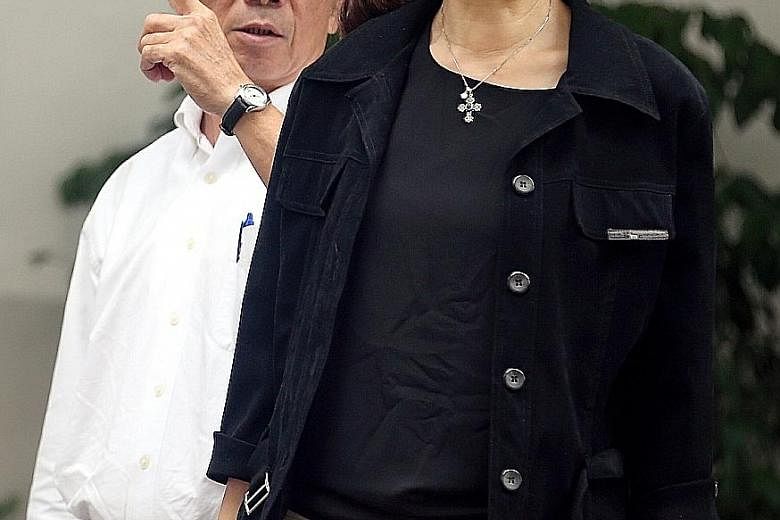

The most recent high-profile case involving Singaporeans accused of corruption-related offences in China was that of Judy Teo Suya Bik and her brother Teo Chu Ha, a former senior director of logistics at data storage company Seagate. They were charged in Singapore last June with 50 counts of corruption-related offences each, involving about 11.1 million yuan.

Judy Teo allegedly obtained bribes from Shanghai Long-Distance Transportation and Feili International Transport as a reward for helping them secure contracts with Seagate Technology International, using confidential information from her brother.

BUSINESS REALITIES

"I'd say close to 90 per cent of Singapore companies here abide by the rules, with one out of 10 that may want to try certain things," says Mr Ching. "And a lot of that has to do with hearsay when they first enter the Chinese market."

Many Singapore firms with sizeable footprints in China declined to speak to The Sunday Times on the record about their experiences here, citing business sensitivities.

But a number of them note that business expenses in China range from lavish restaurant treats to paying for tours and medical expenses, and even buying gifts for clients' children. "If one doesn't play by the rules, you may not get the contract," says one CEO. "China is a big country with a huge population, so the local conditions can be very complicated."

Some firms also encounter outright requests for "commissions", though these are becoming more rare.

Mr Joseph Koh, director of Poh Seng Group, which imports and exports heavy machinery, was prepared to discuss the realities of doing business here, saying: "The quantum depends on the deal. If the contract is small, they may ask for a commission of 5 per cent, and if the deal is big, they will go for 1 per cent to 2 per cent.

"Our company's stance is very clear: We don't do this sort of illicit thing, even if that means we forgo a lucrative contract."

Beijing's anti-corruption campaign has made an example of hundreds of high-ranking "tigers" in government since late 2012 when Mr Xi took power, but it has made little impact on China's global corruption rankings. It is ranked 79th out of 176 countries in Transparency International's latest annual Corruption Perceptions Index, an improvement of one spot compared with 2012.

But both experts and business leaders do say the situation has improved in recent years.

"The campaign and new laws have raised the level of awareness and provided the impetus for businesses operating in China to engage in ethical practices, lest they be embroiled in corruption investigations and prosecutions," says Mr Wilson Ang, a partner with law firm Norton Rose Fulbright.

An amendment to the Anti-Unfair Competition Law which took effect at the start of this month more clearly defines and prohibits commercial bribery, and increases the punishment ceiling 15-fold to three million yuan.

That China still lags behind in global measures of corruption has more to do with how measurements like the Corruption Perceptions Index emphasise conditions such as an independent judiciary, and institutional capacity to monitor corrupt practices, say experts.

"Both domestic and foreign investors have shown confidence in these efforts, pouring trillions of dollars into China's economy over the past three decades despite the fact that it performs badly on most indicators of governance," writes international studies expert Seth Kaplan of Johns Hopkins University.

"These indicators, however, are partly a figment of the Western imagination that exalts narrow political and economic factors and ignores social and cultural dynamics."

While first-tier and coastal cities are shifting away from corrupt practices, Mr Ching notes: "China is growing so fast that suburban cities are also becoming more aware of playing by international rules."