This is part of a weekly series of feature stories, videos and podcasts in which The Straits Times correspondents cast the spotlight on people and communities around the region who are living in the shadows of their societies where they exist largely unseen, unheard and little talked about.

TOKYO/NIKKO (TOCHIGI) – “Growing up, I was embarrassed by myself, by my family and by my living conditions.

“I was embarrassed by my grandmother, who could not read and write because she did not go to school. I was embarrassed by the jobs held by my neighbours. I was embarrassed by how my house was very small, rundown and shabby.

“I kept wanting to escape this life.”

Professor Risa Kumamoto, 48, has indeed come a long way from her childhood home – a hamlet of shunned “untouchables” – and escaped the grips of oppressive poverty and outright discrimination.

Now lecturing at Kindai University in Osaka, she is a respected academic in the fields of human rights research and sociology.

But as a descendant of burakumin (literally “hamlet people”), getting to where she is entailed overcoming a mountain of odds.

Burakumin are the underclass in a centuries-old social hierarchy that is a relic of the feudal shogunate era.

The caste system was outlawed in 1871 and the burakumin “emancipated”, but the yoke of oppression remains.

The burakumin were considered “unclean” for holding jobs shunned by the wider Shinto and Buddhist society – often ones involving animals, blood or death. They include butchers, leather tanners, animal trainers as well as executioners, funeral undertakers and garbage collectors.

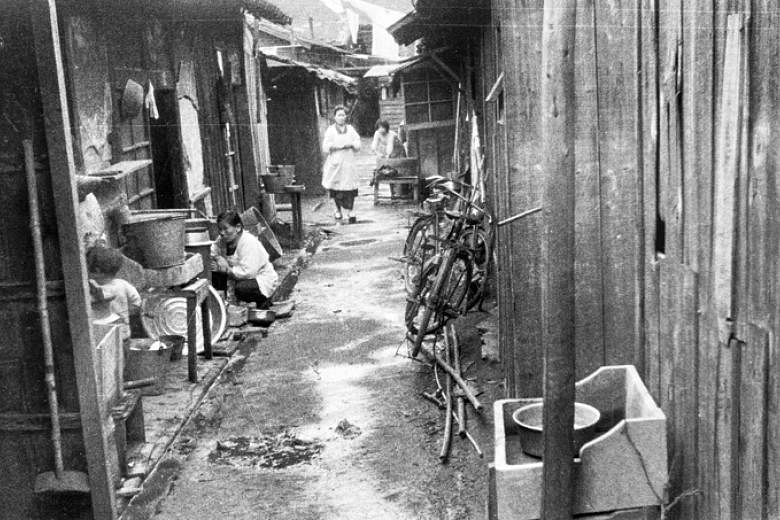

They lived in ghettos – buraku – outside the gated communities of the higher-caste samurai warriors, farmers, artisans and merchants.

They were oppressed by laws that mandated even their hairstyles, the colour of their clothes and the types of shoes they wore.

While no longer shackled by these visible identifiers, the burakumin were, for generations, stuck in lowly paid jobs, with poor educational opportunities and living in rundown housing.

Prof Kumamoto recalled never inviting friends home. On the way home together with her schoolmates, she would alight several bus stops away from her hamlet and walk the rest of the way home. “I just didn’t want them to know that I am burakumin.”

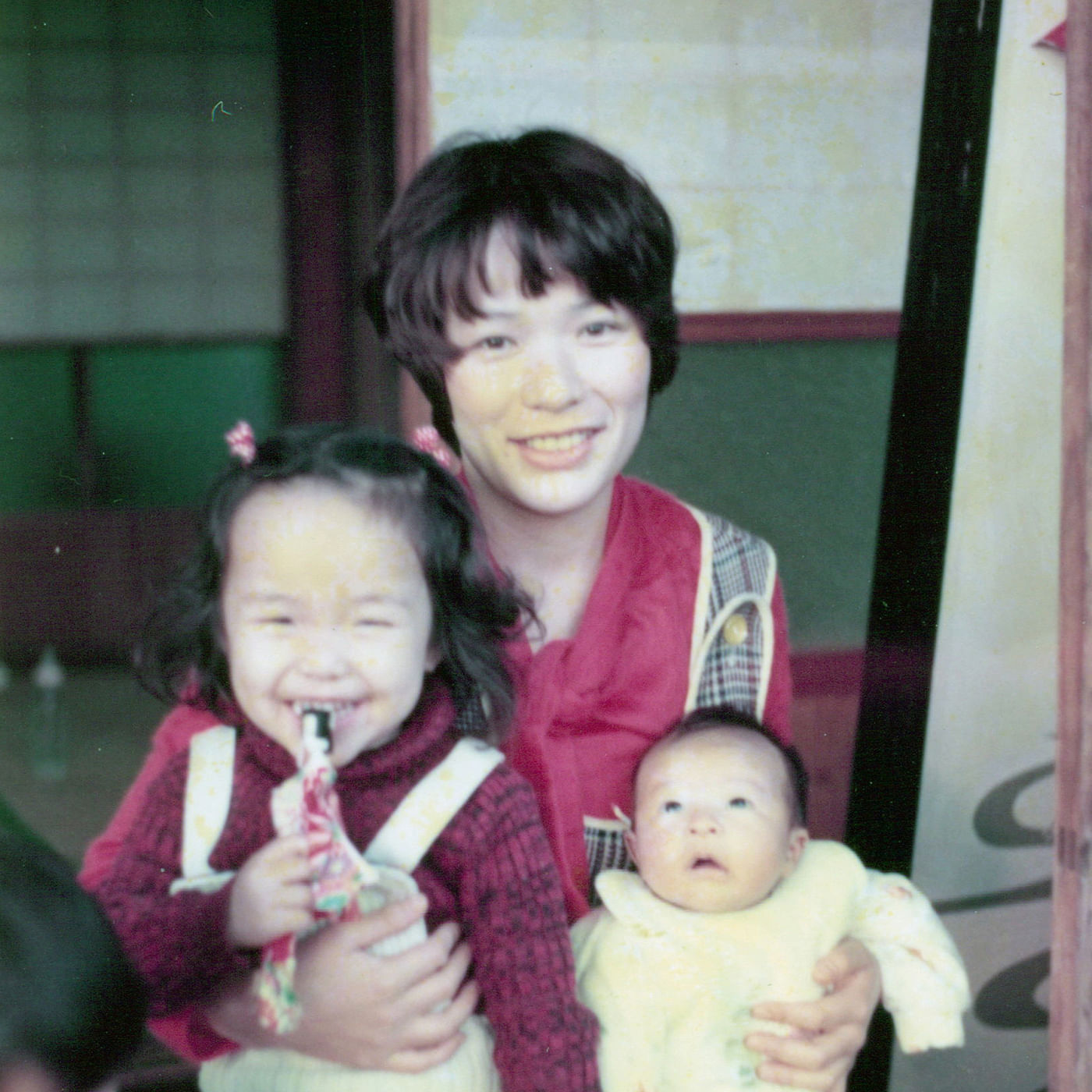

The pain of being burakumin hit home early in life for her. She was six when her parents’ marriage crumbled under social pressure.

“My mother was from a burakumin family in Fukuoka. My father wasn’t. There was huge opposition from my father’s family when they got married. After that, as husband and wife, they were looked down upon. Many things added up over time, leading up to divorce.”

The split made her acutely conscious of being burakumin, even as she and her mother continued living in the hamlet in Fukuoka. Thanks to government policies to help burakumin, she was able to get an education, but her ancestry continued to dog her.

Prof Kumamoto vividly remembers how, in university, her then boyfriend told her to hide her identity. “He told me, ‘You are a good person, but it is better not to mention your burakumin background to my family for your own good. This isn’t discrimination, but mentioning it draws unnecessary attention to it, so it is just better not to talk about it at all.’ ”

Hiding in plain sight

While buraku hamlets have been torn down in areas around and north of Tokyo, they still exist, albeit with facilities modernised and gates torn down, in western Japan areas such as Osaka and Kyoto.

Available official figures, from 1993, indicate that 4,442 such communities existed nationwide.

Today, the Japanese government recognises only those who still live in those hamlets as burakumin – about 900,000, by official estimates.

The Buraku Liberation League (BLL), however, said the actual number is closer to three million.

Many have long moved out of those hamlets and sought jobs without the stigma of what their forefathers had to do.

While most burakumin are no longer recognisable by their jobs or their addresses, prejudice against them manifests in both overt and covert forms.

They have been sent death threats, had their homes vandalised with obscene graffiti or been called names like “scum” and “maggots” on social media. There have also been cases where burakumin were purportedly targeted as convenient scapegoats for crimes without any evidence.

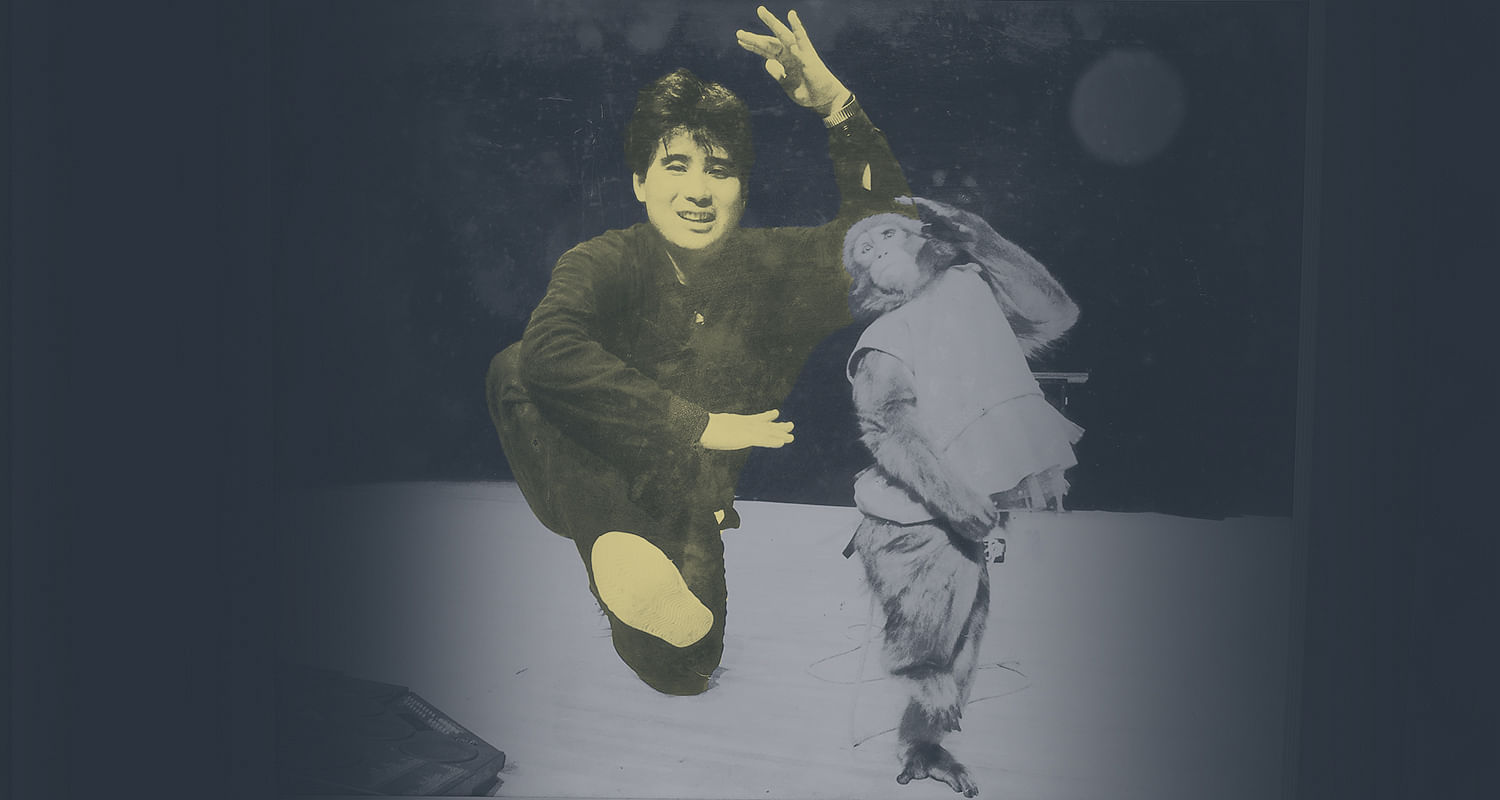

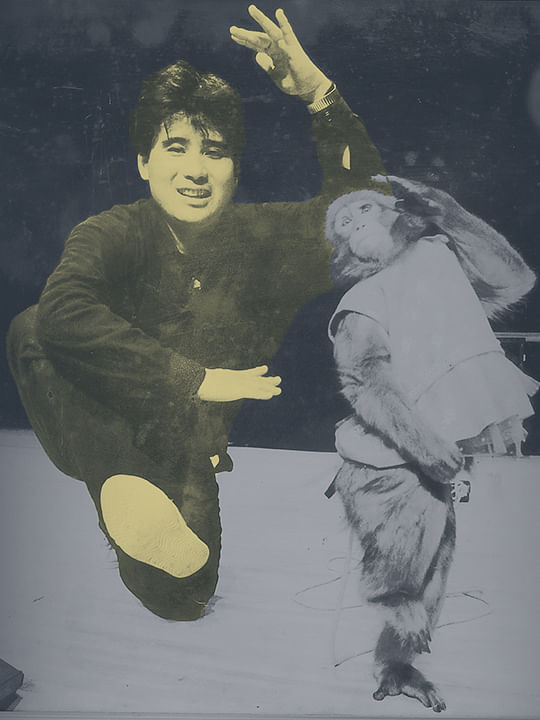

Mr Taro Murasaki, 59, who runs the Osaru Land theme park in Nikko, north of Tokyo, followed in his father’s footsteps as a monkey trainer – one of the so-called “unclean” trades associated with burakumin.

He said people sometimes still refer to him derogatorily as “aiitsu” – or “that person” – presumably because of his caste and profession.

In less-overt cases, burakumin can be bypassed for promotions at work, shunned by their associates or excluded from gatherings with friends. They may also be subject to background checks in employment or marriage.

Family registers kept at town halls could be accessed freely until just decades ago, while old documents with names and addresses of burakumin continue to be circulated on the black market.

Many burakumin will remember how the late former chief Cabinet secretary Hiromu Nonaka was blocked from becoming prime minister when political elite Taro Aso, who is now finance minister, said in 2001: “Are we really going to let ‘those people’ become the leader of Japan?”

BLL vice-chairman Akiyuki Kataoka, 72, told ST that many burakumin conceal their lineage to avoid societal discrimination. It is also common, he added, for many to have chosen not to tell their children of their ancestry in order to protect them.

A special law was passed in 1969 to provide public housing, public health and education facilities and scholarships for the burakumin, who had been routinely neglected for education, jobs and welfare benefits. Some 15 trillion yen (S$184 billion) was spent over 33 years until the law lapsed in 2002.

Preferential placement programmes also helped burakumin secure places in school and municipal jobs, helping their social mobility.

But sociologist Ryushi Uchida of Kansai University told The Straits Times that the law has been perceived as affirmative action by some and fuelled discrimination, while it has also been exploited by some burakumin with links to the yakuza mob. “There have been questions like: ‘Why do those people deserve special treatment?’”

Same case, different place

For Prof Kumamoto, her decision to come out as burakumin came about after she went to Canada to further her studies in the 1990s. Meeting indigenous peoples, immigrants and sexual minorities, she “saw how they had a history of fighting against discrimination”.

It was a huge turning point for her. “Instead of running away, discrimination must be confronted head-on,” she said.

“In the past, I ran away. I hid. I was disgusted by my lineage. But now, I see that my friends can look at society through me. And they can learn about history from my experiences.”

Still, “there is a difference between ‘choosing to come out’ and ‘being outed’ ”, she said, using terms regularly used by the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) community – terms also often used by the burakumin in Japan.

The fact is, efforts to ferret out the burakumin still persist, often in the name of academic research and freedom of speech.

Some 248 persons of burakumin lineage – some of them professors and some others businessmen – have brought a class-action lawsuit against publisher Tatsuhiko Miyabe, 42, for disseminating their names and addresses online. A verdict is due in September.

One of the plaintiffs is Mrs Tami Kamikawa, 41. Her parents were born in buraku communities in Mie and Osaka prefecture, and had met after moving to Tokyo as young adults in the hope of more favourable prospects.

They would have hoped for their daughter to not live through discrimination for being burakumin, but Mrs Kamikawa, who founded non-profit group Buraku Heritage in 2011 to counter the spread of hatred, said hate speech is still disseminated online.

She, too, has struggled with micro aggression in the form of people who deny the struggles of her lineage.

She recalled being upfront about her identity and the struggles her family had faced to her friends and teachers in school. She only learnt about the existence of her aunt in secondary school, after her father told her that she had severed all ties with the family as a condition for marriage – to prepare her for the types of discrimination she may face.

She raised this with her teacher in school, but was plainly accused of exaggerating her concerns.

She recalled being told: “Such buraku prejudice is a historical issue. You must be lying if you say this still exists.”

Mrs Kamikawa told ST: “There are a lot of pent-up feelings from when I have been told to stop imagining things.”

She has not, however, been imagining things.

A government survey in 2017 found that just 11.8 per cent of Japanese believe burakumin discrimination no longer exists, with 40.1 per cent seeing such prejudice in marriage and 23.5 per cent in jobs.

Another, by the Tokyo metropolitan government in 2014, found that 26.6 per cent would oppose their children marrying someone of burakumin lineage.

When it is not just free speech

Led by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the Diet passed an Act in 2016 to “promote the elimination of buraku discrimination”.

The law recognises “the fact that buraku discrimination still exists even today and that the situation has evolved with the increasing use of the Internet”, and seeks to “improve the understanding of each and every citizen on the need to eliminate buraku discrimination”.

It does not, however, impose any punitive measures, and lawmaker Tsuyoshi Yamaguchi, 66, who heads the LDP’s sub-committee on buraku issues, acknowledged that the law is “not forceful enough”.

“There is still discrimination when burakumin are getting married or finding jobs. We need to hasten our efforts for more effective laws,” the six-term lawmaker, whose ward in Hyogo prefecture is home to many buraku industries like leather production, told ST.

Mr Yamaguchi, who is not of buraku lineage, added that even the passage of the watered-down law was problematic.

“The idea of including prohibitive clauses was contentious in the LDP, especially among the more conservative and in the face of the ‘freedom of speech’ counter argument,” he said.

“The law only came into being because (secretary-general Toshihiro) Nikai was driving it. Even (then Prime Minister Shinzo) Abe used to oppose it.”

Asked if Japan was ready for a prime minister of buraku heritage, Mr Yamaguchi told ST: “If one’s great-great-great-grandparent lived in a buraku community, who cares?”

Some municipalities have been more progressive in terms of anti-prejudice ordinances.

Kawasaki, to the south of Tokyo, which is home to a large zainichi (ethnic Korean) population, became the first municipality to ban hate speech last year. Last month, Mie prefecture became the first municipality in Japan to ban the outing of LGBTQ individuals.

For abattoir worker Yuki Miyazaki, this offers a ray of hope for eradicating discrimination against burakumin.

“This momentum must spread nationwide,” he told ST. “Some people defend discrimination as their right of free speech. But how can one person’s rights come at the expense of another’s?”

Mr Miyazaki, 38, who has been working at the Shibaura Meat Market in Tokyo for 20 years, wields a deft hand at preparing cuts of pricey wagyu beef. He has had slurs thrown his way because of his profession – even before he came out as burakumin.

“People can do anything they want to me, but if they attack my two children, I can’t always be there to protect them. I am cautious about revealing my identity because I need to keep them safe. This is a shame as I am proud of my roots and my work.”

Calling for more education at all levels of society, he said: “There is a school of thought that the problem will eventually wither up and disappear if people keep silent, with the idea of ‘not waking up a sleeping child’. I don’t think so. It is important to tell people accurately about history and reality, and have them face up to their own prejudices.”

In the spotlight

Mr Murasaki, the monkey theme park owner, recalled: “When I was young, I always had trouble meeting or dating girls. Once their families knew of my background, they always stopped their daughters from going out with me.”

He took on the job knowing full well that it would be a clear marker of his status as an “untouchable”.

In time, Mr Murasaki found fame appearing on television in his 20s, showing off his monkeys performing skits and playing football and table hockey.

Besides operating his theme park in the city of Nikko, north of Tokyo, since 2015, he and his simian troupe have also been invited to perform abroad.

Despite the insults that he sometimes encounters, he will not hide his lineage.

“With a rise in awareness in human rights and anti-discrimination movements, I want to be true to myself. Rather than hiding in the shadows, it is important to push society to realise there is no reason behind its prejudices,” he said.

“Isn’t it unbelievable that a democratic country like Japan is so stuck?”