What happens when "hehe" means "you are stupid" and "haha" means "get lost"? And to give a treat is "vomiting blood"?

In China, the jiulinghou (literally Chinese born after 1990 who are in their 20s or younger), have their own way of speaking, especially online and over the ubiquitous WeChat social media platform.

It is no joke - one has to use at least six "ha"s to indicate that one is genuinely laughing, according to manuals floating around online deciphering such youth cyberspeak.

China's cyberspace is known for its buzz and vibrancy, being the world's largest with 751 million Internet users as of end June, according to the China Internet Network Information Centre. Three in 10, or 220 million, are aged between 20 and 29.

In China, trendy Internet lingo and memes - a mixture of text and images and text - are hardly trivial. Instead, they have become a barometer of social sentiments, especially among young Chinese, who are more direct, open and individualistic than the older generation.

"If you look at the list of popular catchphrases in 2016, you will notice that the youngsters are feeling tired, anxious and self-deprecatory when faced with rapid developments in society and the mounting stress of life," said new media expert Tian Li of Peking University.

With soaring property prices making it hard for the young to own homes and a growing wealth divide between the masses and the offspring of the rich (fu'erdai), many young Chinese readily embrace sayings that reflect their plight.

-

751m Number of Web users in China as of end June. Three in 10, or 220 million of them, are aged between 20 and 29.

-

Chatting online with youngsters

-

Hehe, it's not funny at all

Do not use "hehe" to denote laughter. To Chinese netizens, "hehe" can connote contempt. "This is a cold response and suggests that the user despises me," said postgraduate student Simon Li. "I won't use it, unless I'm purposely mocking my friends."

As for "haha", it is seen as a perfunctory response where the user is not really interested - it's as good as telling the other party to get lost.

"I don't find 'haha' offensive, but I usually won't use it. I will try to use as many 'ha' as possible to show I'm genuinely laughing," said Mr Li.

Refrain from responding with a single word

Replying using a single "En" (meaning okay) or "Orh" (meaning noted) is extremely unfriendly and indicates that you want to end the conversation. Always use "En, en" or "Orh, orh" if you want to carry on chatting with the other party.

Not all smileys are created equal Youngsters also generally avoid using the smiley emoji, which they describe as "strange" and "vague". To truly express one's happiness, different people have different preferences. Some prefer the shy smiley, others the wide-grin smiley.

Ms Huang Yonglin said the smiley face with a waving hand emoji is one that she swears against. "It means farewell, I won't see you again, and our friendship will end here," she said. "The older folks in my family like my grandparents will send it to me, to genuinely mean goodbye or good night.

"My teacher will sometimes use it too. I feel upset just looking at it. I understand they don't know the underlying meaning to it. But I'd still feel uncomfortable receiving it in text messages."

Ways to end a conversation tactfully

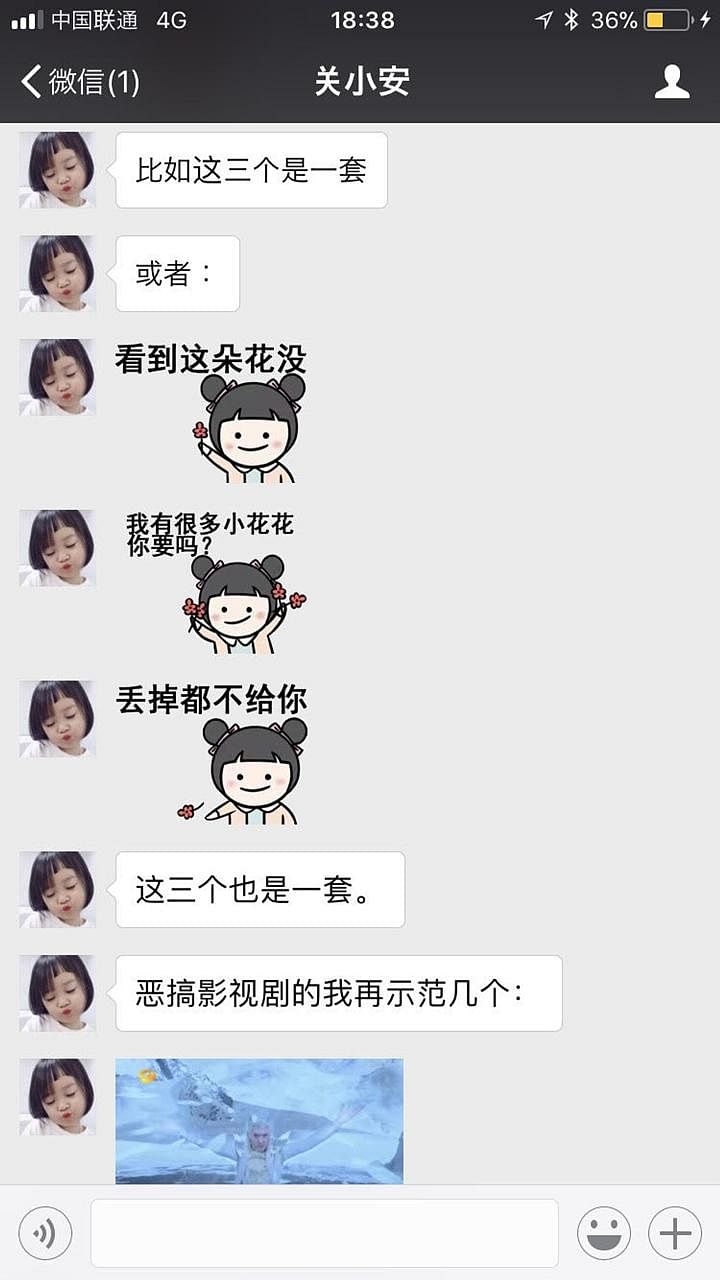

When the other party tells you he or she is going to eat or shower, it is usually a polite way of ending the conversation. Please do not ask why is he or she having a meal at 3pm. When you receive several Internet memes in quick succession, it also means the other party would like to end the conversation.

Messages such as text, emojis and Internet memes are always preferred over voice messages

Visual aids such as emojis and memes can relieve the nervousness or sense of unfamiliarity of people who are chatting virtually. It helps contextualise the meaning of the text in a more vivid way as the parties chatting cannot see one another's expressions and body language.

Youngsters tend to avoid sending voice messages, especially with people they don't know well. "It's an intrusion... They can't see the messages and got to go listen," said Mr Li.

Chong Koh Ping

Some of these popular sayings include ganjue shenti bei taokong - feeling sapped of all energy - as well as ni za bu shang tian - literally why don't you go to the sky but really meaning fat hope.

As active Internet users, youngsters are the main drivers behind online catchphrases as well as emojis and memes, which are a combination of text and images.

The catchphrases and memes are inspired by hot button issues, quotes from notable people, animation, TV and movies. Some are also created by online content producers.

These days, many young Chinese type messages using the formal language taught in school as well as cyber lingo, so much so they have to remember to code switch.

"When I talk to my close friends and family, I'm very free with using emojis and Internet memes. I will use whatever, whenever I like," said postgraduate student Simon Li, 25.

"With my supervisor in the university, I won't use any emoji or Internet memes at all. At most I'd use the sun emoji to show I'm enthusiastically accepting his views and comments," he said.

Associate Professor Tian told The Straits Times one trend is a move away from text-based catchphrases to visual images and animated gifs.

In a survey conducted in the first half of last year with nearly 320 students at Peking University, 75.6 per cent said they "frequently use emojis", and 15.4 per cent said they will "use emoji in almost every sentence". Less than 1 per cent said they "never use any emoji".

Prof Tian noted that such Internet symbols carry more information than the written word.

"They help to speed up communication and can transmit more information with richer content in a shorter time," she added.

Singaporean Tan Bao Jia, 27, agrees that youngsters in China use a lot more emojis and memes in instant messaging - at least compared with her days as a Peking University undergraduate from 2009 to 2013.

Ms Tan, who works at an international organisation based in Beijing, said: "Young people tend to be more direct in the way they speak, so symbols and pictures can often help soften the impact."

Postgraduate student Huang Yonglin, 23, said the use of memes and emojis conveys friendliness.

She told ST: "Whatever it is, you should always respond with a couple of words or an Internet meme or an emoticon or a combination of these to show your friendliness."

Ms Huang is certainly a fan of Internet memes - she has 300 such graphic icons in her WeChat, the maximum number allowed. "So every time I want to add new ones, I've got to delete some others."

A no-no is one-word responses. She said: "I ban my boyfriend from sending me one-word responses. He must say 'Oh, oh' ('en, en') or 'Yes, please'. ('hao de') It's very hurting to get a one-word response."

Ms Tan has also observed new expressions being coined at a faster pace. "The use of '666' to mean cool or impressive is quite bizarre to me. Such expressions seem to originate from the gaming community. And I think there's more of them now." In Chinese, six is liu, pronounced similarly as the word meaning smooth and also slang for "awesome".

Given the wide use of Internet catchphrases, some fear that these will adversely affect the proper use of the Chinese language, especially among young students.

In an interview with the Chinese Communist Party-run newspaper Guangming Daily earlier this year, Mr Yao Xishuang, a director with China's Ministry of Education, said the phenomenon of Internet catchphrases is a double-edged sword.

He added: "While we recognise that they can enrich the development of (the Chinese) language, some of them can also be out of line and unhealthy. We should not completely outlaw them, but neither should we allow them a free rein."

But not all worry about China's colourful cyber youth lingo.

Some older folks or even foreigners enjoy expanding their repertoire of expressions.

Business executive Wang Yong, 42, collects Internet memes that his staff in their 20s send him.

"They communicate in a very different way. For me, I'm more willing to accept new things, so I can adjust. So we won't end up in a 'ga liao' situation," he said, using a catchphrase which means having an awkward conversation.

As for Ms Tan, who has moved to Beijing for only six weeks, she enjoys learning new phrases such as "You're stabbing my heart, old friend" ("zha xin le, lao tie"). Tie, which means steel, is used to denote close buddies in the north-eastern dialect. She said: "This is a creative play on words, because language as a thing in itself is an expression of culture."